Ferrari

This is the first of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

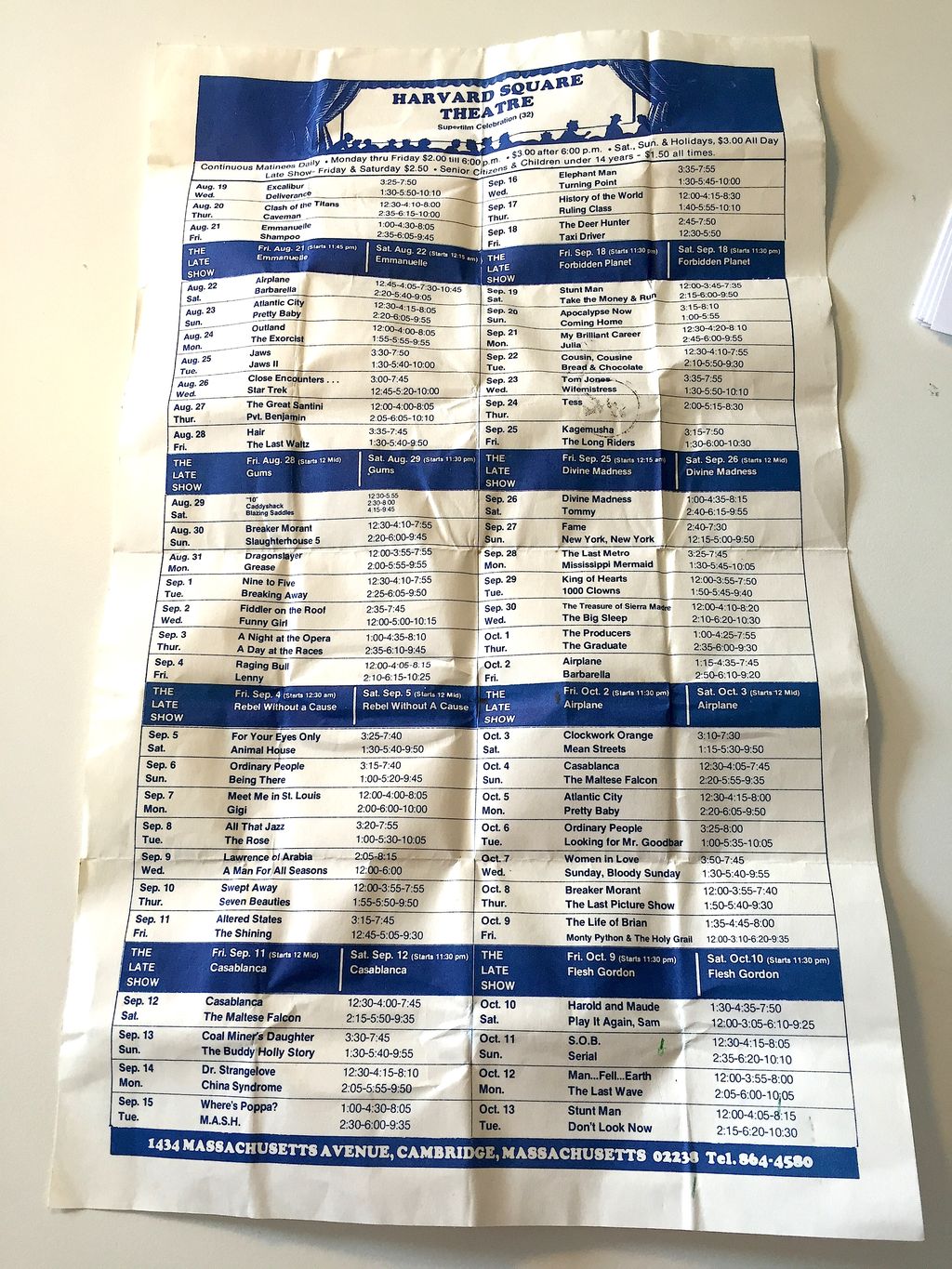

Those familiar with the squared-circle “G-schema” that I have in recent years developed — as a superior tool for mapping the mutually and reciprocally defining terms of any given semiosphere — will already be aware that once he, she, or they have concluded a semiotic audit’s “thin-description” phase (e.g., research, close reading, initial pattern-spotting), the G-schema-oriented semiotician must now commence brooding over these fragments, for hour upon hour, asking Foucauldian questions: What’s the dominant discourse? What set of ideas, values, and assumptions is taken for granted, and thus helps guide perceptions and behavior, within the context of this semiosphere? Or else, if you prefer, an early-Barthesian version of the same question: What ideology or “myth” is presented, in this semiosphere, as natural, inevitable, and permanent — thus masking its constructed nature and helping to perpetuate the status quo?

Thus begins the arduous yet thrilling and deeply satisfying “thick-description” phase of a G-schema-oriented semiotic audit.

The dominant-discourse paradigm can be thought of (to leverage Freud’s useful, if incomplete, structural model of the personality) as the semiosphere’s Über-Ich, its superego. It’s the semiosphere’s self-critical conscience, charged with sanctioning (officially approving) socioculturally legitimate feelings and actions, while remaining poised to impose sanctions (discipline, punish) whenever the rules are transgressed.

My clients, on whose behalf the majority of my G-schemata have been developed, might warn the newbie semiotician that identifying a semiosphere’s dominant-discourse “paradigm” (in my idiosyncratic use of the term) is merely the first step. In total, each G-schema will eventually boast eight paradigms: These are the avatars or manifestations, if you will, of eight key positions on/in the G-schema. Four paradigms represent the G-schema’s four territories; the other four represent the end points of the two axes that (literally) delineate these territories. The latter paradigms represent tricky, revelatory hybrid positions, i.e., half-in and half-out of adjacent territories.

Each paradigm “governs” — my deployment of astrological terminology, here, I’d ask you to understand, is an example of engaged irony, on which topic I’d be happy to expand, tediously, should we ever happen to meet at a cocktail party — two of the G-schema’s sixteen thematic complexes. I hasten to add, though, that it would be equally accurate to say that each of a G-schema’s eight pairs of thematic complexes “projects” (or, say, “extrudes”) its governing paradigm. It’s a chicken-and-egg question; the G-schema’s complexes and paradigms are — this time, I’m borrowing terminology from the logic of Taoism — mutually generative and supportive.

Need a visual aid, at this point? Take a look at the Casablanca G-schema, below. Each of its red and blue vertices shows the constitution of a paradigm by two thematic complexes — or, it would be equally accurate to say, the constitution of two thematic complexes by a paradigm.

A note on method: The G-schema-oriented analyst’s effort to surface and dimensionalize a semiosphere’s paradigms, each of which is mutually and reciprocally defined (in contradictory and contrasting ways) by the other seven, cannot be separated from the effort to surface and dimensionalize a semiosphere’s thematic complexes. In fact, during the audit’s thick-description phase, one will incessantly toggle back and forth between the semiosphere’s “levels” (if a sphere can be said to have levels; this is the downside of topographical metaphors), in a vertiginous pushmi-pullyu process that Dilthey dubbed the “hermeneutic circle” — i.e., a [spiraling, I’d say, not circular] process in interpretation where understanding parts of a given “text” relies on understanding the whole, and vice versa.

As noted previously, this giddying voyage of discovery begins — in my own methodology, at least — with the quest to identify a semiosphere’s dominant-discourse paradigm. (Also known, depending on which theorists you read, as its “structural matrix,” or “master code”). Once we’ve successfully done so, the G-schema’s mechanism will guide us to further revelations.

Turning our attention to the almost universally beloved* 1942 romantic drama / espionage movie / film noir / propaganda effort Casablanca [d. Michael Curtiz, w. Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, Howard Koch], after much brooding and tinkering I can confidently announce that the two (contrasting, not contradictory) thematic complexes comprising this text’s dominant-discourse paradigm are: BLACK MARKETEER and CRIME BOSS.

The determinative, taken-for-granted assumptions (or the natural-ized myth, if you prefer) of Casablanca have to do, that is, with an illicit/criminal network of operations that commands at least as much authority, power, and influence as do Casablanca’s corrupt authorities.

* I tend to agree with Manny Farber that Casablanca is overrated, and with Umberto Eco that Casablanca is “a very mediocre film.” However, the movie (about which Eco also said: “There is a sense of dizziness, a stroke of brilliance.”) is a terrific subject for a G-schematized analysis. Also, during the run-up to and aftermath of the United States’ 2024 presidential election, I found it comforting to watch anti-fascist propaganda made in America. Happy Inauguration Day….

The dominant-discourse paradigm, in a G-schema, is always positioned at the juncture of two of the semiosphere’s four territories. In this case, our analysis indicates that BLACK MARKETEER is one of the four thematic complexes within the Casablanca territory WAR; while CRIME BOSS is one of the four complexes within the Casablanca territory BUSINESS. War and business are what Casablanca, the city (as depicted in this fictional movie, anyway), is all about; Casablanca, the movie, however, will also reveal oppositional territories: PEACE and PLEASURE. But for the moment, let’s focus on war and business.

In the movie’s first moments, we’re shown newsreel footage of refugees fleeing Europe’s war zones and fascist states. Some of them are headed to Casablanca, the Moroccan port city (which at the time of the movie’s action — December 1941, days before the Attack on Pearl Harbor — was occupied by France, which in turn was partially occupied by Germany), desperately hoping that they might “obtain exit visas and scurry to Lisbon; and from Lisbon, to the New World.” While they cool their heels in Casablanca, these wretched souls are robbed by pickpockets and grifters, exploited financially and sexually by corrupt officials, and squeezed for what few valuables they might still possess by mercenary people-smugglers.

To quote Star Wars, a movie that — as we’ll point out at appropriate moments during this series — offers multiple homages, at the levels of both form and content, to Casablanca, the desert outpost into which we viewers have been transported is a “wretched hive of scum and villainy.” Casablanca is a crapsack world where “everybody,” as Rick Blaine will tersely inform Annina Brandel, a naive refugee from Bulgaria, “has problems.”

We’ll explore the Casablanca thematic complexes BLACK MARKETEER and CRIME BOSS further in the current series installment, but let’s pause here to ask: Who’s in charge? Which character exemplifies the paradigm that “governs” these themes? Which character has (illicit) authority, power, and influence in both the WAR and BUSINESS territories of this all but lawless semiosphere?

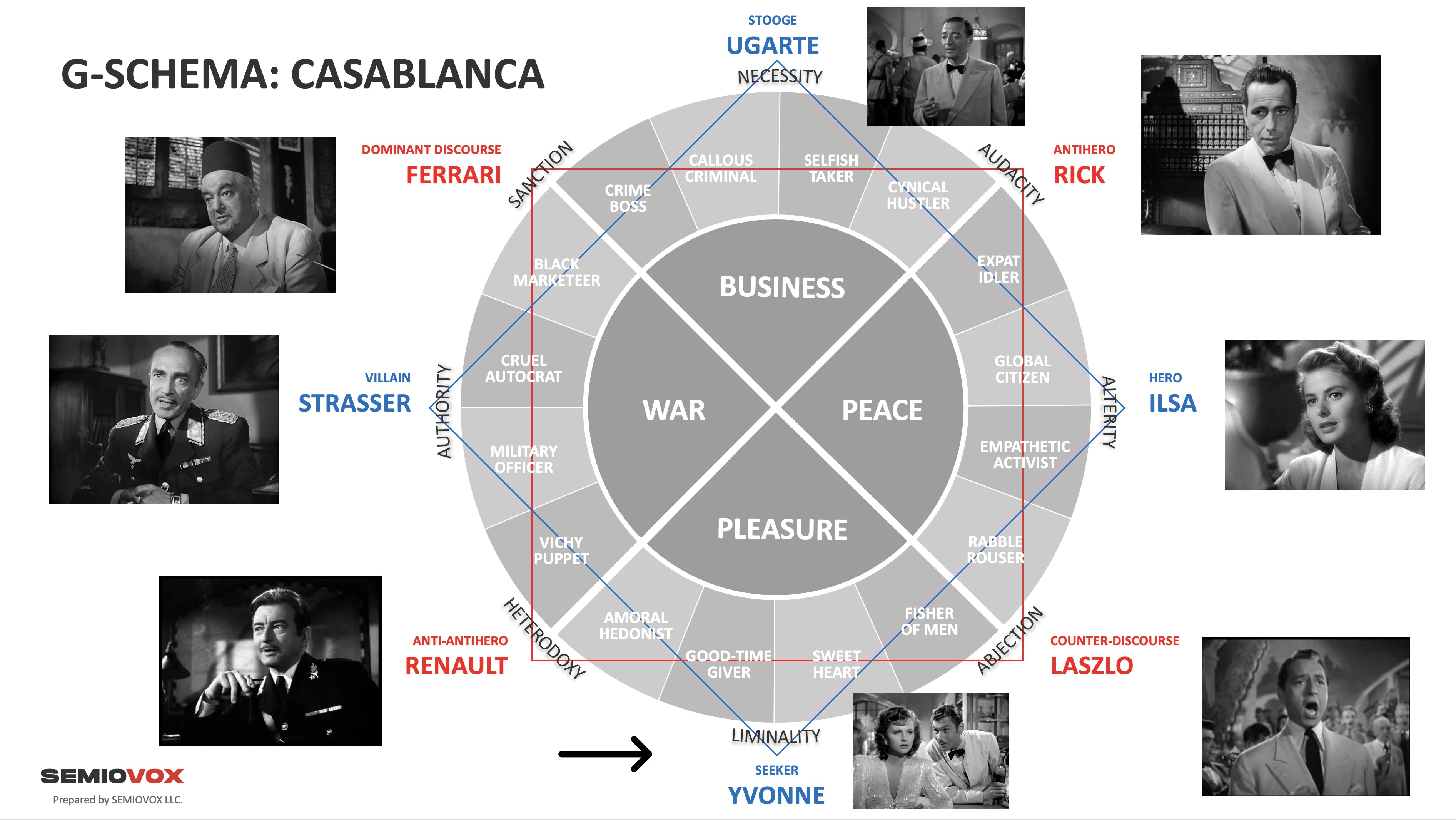

“As the leader of all illegal activities in Casablanca,” Sydney Greenstreet’s fez-sporting character, the nominally Italian crime boss Signor Ferrari, announces without a trace of shame or even circumspection (thus demonstrating the validity of our hypothesis about this semiosphere’s dominant discourse), “I am an influential and respected man.”

The avatar of Casablanca’s dominant-discourse paradigm is: FERRARI.

A quick note about Greenstreet. Although the actor had been a well-known figure in British theater since the early twentieth century, he wouldn’t appear in a single movie until John Huston cast him (at age 62) as Kaspar Gutman, aka “the Fat Man,” partner-in-crime to Peter Lorre’s Joel Cairo in 1941’s The Maltese Falcon. Greenstreet would go on to play heavies (if you will) in Background to Danger, Mask of Dimitrios, Passage to Marseille, and Three Strangers, all of which also feature Lorre, and one of which features Bogart; he and Lorre also played good guys, once in a while. He wouldn’t make a film after 1949.

CRIME BOSS

If, on the surface of things, i.e., from the perspective of new arrivals, the city of Casablanca appears to be governed and policed by lawfully elected or appointed authorities, this mummery is merely the tribute that vice pays (literally, in the form of bribes and kickbacks) to virtue. Newcomers will soon be disabused of their illusions: Throughout the movie, we catch glimpses of a representative pair of refugees — Bulgarian newlyweds Jan and Annina Brandel, played by fresh-faced actors (aged 24 and 18 at the time) — going through precisely this process. The denizens of Rick’s Café Américain are depicted as occupying a range of positions along the continuum from naively optimistic to cynical and despairing; they are souls trapped in limbo.

In the fictional city of Casablanca, as is also the case within the Casablanca semiosphere, the fantasies of libertarians have been fully realized: Here, the market is truly free — anything and everything goes. “Instrumental reason,” to employ Horkheimer and Adorno’s term for the social and political shift in priority from ends to means, i.e., from worrying about the larger meaning and purpose behind goals to caring only for the efficiency with which those goals are achieved, has triumphed over moral reason. Instrumental reason is represented by FERRARI; moral reason — which threatens Ferrari’s empire — comes to town in the form of LASZLO and ILSA. And as Ferrari no doubt shrewdly intuits, moral reason also lurks in Rick Blaine’s heart; this, as far as Ferrari is concerned, is Rick’s Achilles heel.

Though not exactly a crucial figure in the movie’s plot*, Signor Ferrari does play a key structural role — i.e., because FERRARI is the avatar of Casablanca’s dominant discourse.

*Except, of course, for the scene in which he leaks key intel to Victor and Ilsa.

Ferrari first appears at 16:30, while Sam and the band at the Café Américain perform the song “Knock on Wood.” (“Who’s got nothin’? / We got nothin’! / How much nothin’? / Too much nothin’!” — an ironic walk-up song for a character who has everythin’ — too much everythin’.) As he approaches the table where a local Muslim confederate has reserved him a prime seat, Ferrari offers the fez-wearing fellow a “salaam” hand gesture while slightly bowing; the man stands and does the same. It’s a small moment, but it signals (literally) that — unlike Rick Blaine — this European has gone local; he’s embedded himself, for better or worse, deeply into Casablanca’s society and culture; and he’s a figure who commands respect. He’s here, that is, to stay.

We don’t ever see Ferrari engaged in criminal activity. Like all mafia bosses, he knows how to keep his own hands clean. Retrospectively, though, we’ll realize that some of the illicit operatives we’ve earlier glimpsed doing business in Rick’s cafe — a guy in a fez buying diamonds from a refugee, perhaps, or the men speaking in Chinese — are likely controlled, directly or indirectly, by Ferrari. Ferrari isn’t merely a crime boss; he’s the crime boss in Casablanca. But to the general public, he represents himself as merely the proprietor of the Blue Parrot bar, a seedier rival of Rick’s Café Américain. As such, he’s come here this evening to make an offer that Rick can’t refuse: He wants to purchase the Café Américain lock, stock, and barrel; this includes the staff. Note that although the restaurant, bar, and nightclub are a profitable business, surely what Ferrari cares about most is the back-room casino. The cafe, really, is just a swanky front for the real business.

Rick does refuse Ferrari’s offer, and in no uncertain terms. This doesn’t suggest that Ferrari is a legitimate businessman, so much as it suggests that Rick, too, is engaged in illicit activity. He’s a rival crime boss, of sorts — one who has cornered the market on gambling, as far as we can ascertain. Which explains why these two characters warily respect one another.

Respect and honor are, of course, the currency in which fictional crime bosses — “Dons” — deal amongst themselves. Theirs is a tribal-esque social order, we’re given to understand, one characterized by “total prestations,” to use Mauss’s descriptor for potlatches and other competitive exchange practices via which high-status sociocultural roles are maintained. In this crime-dominated semiosphere, then, respect is the most precious commodity to be found in the BUSINESS territory. Ferrari’s salaaming, earlier, was a courtly act of respect; in a later scene, he’ll order a waiter at the Blue Parrot to bring Rick “the bourbon” — another respectful ritual.

Let’s not confuse respect with trust or friendship. As TV Tropes puts it, in their write-up of the “Don” type, much like fictional “trope codifiers” Vito and Michael Corleone, a Don is “shrewd, ruthless, and very dangerous to cross. Often he will hold to an arcane code of honor, which is perhaps incomprehensible to non-mobsters.” The entry goes on to explain that “the Don may be willing to use coercion, bribery, and murder to achieve his goals, but there will remain lines he won’t cross.” Greenstreet’s silky-smooth, overtly friendly, yet sinister performance suggests that if he weren’t dealing with Rick, a respected compeer [fun fact: the term, which now means “equal,” derives from the medieval Latin for “godfather”], Ferrari wouldn’t be making his offer, or accepting its rejection, so cordially.

Like FERRARI, a paradigm straddling two of this semiosphere’s territories, the paradigm RICK isn’t entirely about BUSINESS. But whereas FERRARI’s other foot (so to speak) is in the WAR territory, RICK’s is in the PEACE territory. Despite their similarities in the BUSINESS territory, then, the two characters are structurally opposed to one another… which, at some level, they both understand.

This structural insight helps us to make sense of Ferrari’s mien — his look and manner — in his dealings with Rick. Ferrari may respect Rick as a man of business, but he is a hawk while Rick is a dove (a “dove” who has sold arms to anti-fascist organizations, so he’s not anti-war so much as pro-peace by means of armed resistance). Ferrari no doubt suspects that Rick will at some point soon drop out of the business game and re-enter the struggle against fascism. Which is why he astutely makes an offer to purchase the Café Américain now, and also why he so blithely accepts Rick’s rejection. Perhaps his chess-master-ish goal was to plant a seed, to hasten a process already at work in Rick’s mind, one that will eventually result in Ferrari’s success.

Everyone in Casablanca, it seems, understands Rick’s heart better than Rick himself does.

Structurally speaking, the foregoing analysis ought to help us to think about the relationship — in any structure, fiction or nonfiction — between the dominant-discourse paradigm and the antihero paradigm. (Rick Blaine is a classic antihero, there’s no spoiler in saying so now.) The antihero may hold the dominant discourse in contempt… but not entirely so, because the antihero wants — well, the antihero doesn’t want to be forced to decide between their semiosphere’s dominant discourse and its counter-discourse. They desire the perqs of their semiosphere’s dominant discourse, without the attendant responsibilities and obligations; they are all id, no superego. Meanwhile, the dominant discourse may be troubled by the antihero’s rebellion, but they also find it charming, even alluring — precisely because the antihero refuses to decide in favor of the counter-discourse. They can still do business….

A note here, about Jabba the Hutt — the large, slug-like crime lord of the desert planet Tattooine who is mentioned but not shown in the original 1977 version of Star Wars and its sequel, 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back. (He finally shows up in 1983’s Return of the Jedi.) Much as the lawless spaceport Mos Eisley, which Obi-Wan Kenobi describes as a “wretched hive of scum and villainy,” and the denizens of which are closely monitored by agents of an occupying force, owes a large debt to the depiction of Casablanca in Casablanca, so too does Jabba — who at one point was perhaps going to wear a fez — owe a debt to Ferrari. (In fact, the Mos Eisley cantina bears more of a resemblance to Ferrari’s Blue Parrot than it does to Rick’s Café Americain.)

But Jabba has nothing of Ferrari’s charm or wit; he is a crude caricature, a Muppet version of Ferrari. And a two-dimensional caricature, too, since Jabba is a crime boss, but not (as far as we know) a black marketeer….

BLACK MARKETEER

Although in some contexts “black marketeer” is more or less synonymous with “crime lord,” and “black market” with “underground economy,” in Casablanca although the two roles may overlap to some extent, they are readily distinguishable.

Just before a scene that will take place in the Blue Parrot, for example, yet another fez-wearing character — a fellow at an open-air desk with writing quills and equipment for melting wax and making seals, thus apparently a forger of official documents, informs a refugee, before apologetically handing him back his passport: “This is a job for Signor Ferrari.” “Ferrari?” the refugee demands. Smiling, the forger explains: “He pretty near has a monopoly on the black market here. You will find him at the Blue Parrot.”

The forger may be engaged in criminal enterprise, but when it comes to the black market — that’s something else, he insists, entirely. The black market, in Casablanca, at least during this period, is an economy dedicated to smuggling refugees out of occupied Europe, among other illicit acts related to the war. In an utterly nonheroic way, the black marketeers are deploying their criminal networks to perform acts of resistance against the occupying forces. Smugglers of cigarettes and liquor now also smuggle refugees. It’s the same covert network, but in wartime it’s… different. Another way to put it: In Casablanca, while all black marketeers are criminals, not all criminals are black marketeers. Rick himself, for example, runs an illegal casino, but he won’t help refugees escape… He wants nothing to do with any sort of wartime resistance effort.

Unlike Rick, Ferrari is more than willing to get involved with people-smuggling and other profitable acts of resistance — no doubt he’s into arms running, stealing supplies from the German military, sabotage, and so forth. At the same time, we can readily imagine that he might also collaborate, as necessary, with Vichy France and the Nazis. *

* Note the juxtaposition, on our G-schema, of the thematic complexes BLACK MARKETEER and CRUEL AUTOCRAT. Which would suggest collusion between Ferrari and the Nazis isn’t out of the question.

Let’s pause, here, to consider a real-life Signor Ferrari: Enzo Anselmo Giuseppe Maria Ferrari Cavaliere di Gran Croce (1898–1988), the Italian motor racing driver who — just before WWII — founded the now-iconic Ferrari automobile marque.

In adopting the personal emblem — a prancing black horse on a yellow background — of Francesco Baracca, WWI’s most renowned Italian military aviator, for the logo of his racing team and marque, Ferrari cannily benefitted from the logo’s association with an Italian military hero… certainly with the militaristic Mussolini, who’d just a few years earlier had declared himself Italy’s fascist dictator. Later, during the civil war that raged in Italy during WWII, one reads, Enzo was a uniform-wearing member of Italy’s National Fascist Party, and his Modena factory cranked out war materials for Italy and Germany.

And yet… Ferrari also helped arm the Italian Socialists who during that same period became the primary force in the resistance against Mussolini and the country’s Fascist regime. He colluded strategically with both sides, that is, in order that his business might continue to thrive. An intriguing parallel.

Though most likely he’s come to some sort of arrangement with the Vichy administration that controls Casablanca, we never see Ferrari working directly with the bad guys. Casablanca’s black market flourishes in defiance of Vichy and the Nazis. The guys we spot, at Rick’s cafe, making quiet plans having to do with trucks and men over a game of dominoes — they might work for Ferrari. The smuggler who offers to transport a refugee (who looks like Walter Benjamin, doesn’t he?) on a fishing smack, for a hefty cash fee — he no doubt works for Ferrari, too.

In his first scene, Ferrari references such activities. After Rick says that his cafe is not for sale at any price, Ferrari responds: “What do you want for Sam?” This is a grim moment — a White man seemingly offering to purchase a Black man. Ferrari doesn’t mean it like that, exactly, but again perhaps he’s purposely trying to reawaken the idealistic humanitarian, in his business rival (in order to drive his rival out of business). If so, the racist-ish provocation works beautifully. Taking the bait, Rick replies: “I don’t buy or sell human beings.” At which point, Ferrari makes a second offer to Rick: “Too bad. That’s Casablanca’s leading commodity. With refugees alone we can make a fortune if you’d work with me through the black market.” That is, Ferrari is exploiting those who seek to “obtain exit visas and scurry to Lisbon — and from Lisbon to the New World.”

When Rick declines this second offer (“Suppose you run your business and let me run mine.”), Ferrari makes a pointed political joke, describing Rick’s refusal to get involved in the semiosphere’s WAR territory as “isolationism” — and suggesting, in a silkily menacing way, that this is no longer a “practical policy.” By “practical,” he means “profitable” — but weirdly enough, this is also part of the movie’s propaganda effort. The first appeal, that is, to the movie’s American audience, to abandon neutrality and take a side in WWII, comes from the mouth of… Ferrari!

Later, we find Ferrari again attempting to do business with Rick, this time on his home turf. At the Blue Parrot (which actually looks more fun, if much less swellegant, than Rick’s cafe), he tells Rick that he’s all but certain that Rick has valuable letters of transit (the movie’s MacGuffin), and that he’ll sell them on the black market for a small percentage of the price. Because Rick, structurally speaking, is involved in the BUSINESS but not the WAR territory of this semiosphere, he lacks the wherewithal to sell the letters of transit safely and profitably. “You need a partner,” he insists; and if Rick were interested in selling the letters of transit, he’d be absolutely correct.

But perhaps what the chess-master* is doing here, once again, is not so much trying to make a deal that he surely knows won’t happen, but instead forcing Rick to begin moving away from the semiosphere’s WAR territory and towards the PEACE territory (where, as Ferrari knows, Rick belongs).

*I’ve called Ferrari a chess-master a couple of times, in this installment, though it’s Rick whom we see studying a chess game, when we first meet him. This appears to be a “correspondence” game, i.e., chess played by people who are geographically distant. One wonders if Rick (himself a chess master) might be playing the game against… Ferrari?

During the Blue Parrot scene, Rick spots Victor and Ilsa outside — and realizes that they’ve become examples of what Ferrari called “Casablanca’s leading commodity”; they’re hoping to meet with Ferrari to arrange their escape via the black market. Hoping to apologize to Ilsa, Rick exits hastily. Although Ferrari gives no indication of having noticed the reason for Rick’s uncharacteristically awkward behavior, of course he notices everything — which explains, one suspects, what happens next.

Victor offers a princely sum to Ferrari in exchange for his assistance in smuggling the two of them out of town, but Ferrari won’t play ball. “I might as well be frank, monsieur,” he explains. “It would take a miracle to get you out of Casablanca, and the Germans have outlawed miracles.” He also tells Victor and Ilsa that helping them could easily cost him his life. This can’t be true, though; surely Ferrari, the black-market monopolist, could smuggle Victor and Ilsa out. He’s playing a deep game, here. What’s he up to?

Ferrari persuades Victor to remain behind in Casablanca, while he smuggles Ilsa out of town; and once Ilsa joins them, Victor attempts to persuade her that this is a viable option. She won’t hear of it; structurally speaking, Ilsa is not a damsel in distress, but a heroine. But one can be certain that Ferrari had anticipated that this initial stratagem of his — a feint — would fail. Having manipulated them into a state of desperation, he’s ready to try a new gambit. As Victor and Ilsa prepare to leave the Blue Parrot, Ferrari says: “I am moved to make one more suggestion — why, I do not know, because it cannot possibly profit me. But… have you heard about Signor Ugarte and the letters of transit?” He suggests to Victor and Ilsa that they importune Rick for the letters of transit — thus cutting himself out of the bargain. Why?

For starters, LASZLO is the avatar of this semiosphere’s counter-discourse; he represents PEACE and PLEASURE, whereas Ferrari represents WAR and BUSINESS. Despite Ferrari’s outward cordiality and sympathy, then, structurally LASZLO is the abject other that FERRARI must at all costs eject from the semiosphere. So Ferrari does want Laszlo out of Casablanca, but… Ferrari cannot help Laszlo escape directly, only indirectly. Besides, Ferrari would never do anything unprofitable.

Most Casablanca viewers, reviewers, and scholars, however, seem to agree that Ferrari’s last-minute brainstorm demonstrates this villain’s well-concealed “heart of gold.” Ferrari is, according to this reading — to quote Renault’s favorite thing to say about Rick — a rank sentimentalist. It’s these misguided Casablanca exegetes who are rank sentimentalists. Ferrari doesn’t have any soft spots.

In Robert McKee’s bestselling screenwriting book Story, which is required reading for film and cinema schools at Harvard, Yale, UCLA, and elsewhere, in a section on “The Problem of Holes” (i.e., missing links in a screenplay’s chain of cause and effect), we read the following:

CASABLANCA: Ferrari (Sidney Greenstreet) is the ultimate capitalist and crook who never does anything except for money. Yet at one point Ferrari helps Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) find the precious letters of transit and wants nothing in return. That’s out of character, illogical. Knowing this, the writers gave Ferrari the line: “Why I’m doing this I don’t know because it can’t possibly profit me…” Rather than hiding the hole, the writers admitted it with the bold lie that Ferrari might be impulsively generous. The audience knows we often do things for reasons we can’t explain. Complimented, it nods, thinking, “Even Ferrari doesn’t get it. Fine. On with the film.”

McKee’s analysis is frequently quoted to explain Ferrari’s behavior in this scene, but I don’t buy it!

Ferrari isn’t being impulsively generous — if he was, he’d go ahead and smuggle Victor and Ilsa out himself, free of charge — or at a reduced price. Instead, his shrewd observation of Rick’s behavior regarding Ilsa has encouraged the chess master to attempt, yet again, to reactivate Rick’s sense of morality and compassion. True, if he succeeds in this gambit, he’ll lose access to the letters of transit… but unlike everyone else in the movie, Ferrari seems cynically aware that these are just a MacGuffin.

Structurally, if Ferrari’s final gambit does succeed, Rick’s effort to help Laszlo and Ilsa will remove RICK from the semiosphere’s BUSINESS territory and move that “chess piece” into the PEACE territory… which will result in Rick selling the Café Américain to Ferrari. A prize worth far more than any letters of transit.

Ferrari’s “why I’m doing this I don’t know” handwringing is, according to this structuralist analysis, nothing more than manipulative theatrics.

When Ferrari swats at a fly, just after Victor and Ilsa leave, this is his surreptitious version of punching the air in triumph.

The next and final time we meet Ferrari, he once again makes a ritual gesture of respect, pouring a cup of tea for Rick. NB: I’ve added a separator (above), because this final scene depicts Ferrari as both a crime boss and a black marketeer.

Over tea, Ferrari and Rick negotiate sharply but amicably over the sale of the Café Américain. Though Rick appears to win these negotiations, who knows what Ferrari will do once Rick leaves town? After all, it’s just a handshake arrangement. As a crime boss, Ferrari has succeeded at last in taking over Rick’s gambling operation; this wouldn’t have been possible, though, if it weren’t for Ferrari’s role as head of the war-related black market, thanks to which he was finally able to manipulate Rick.

Which teaches us something about the dominant-discourse paradigm in all such narratives. Structurally speaking, its position as “governor” of two of the semiosphere’s territories offers it a crucial advantage. Assets in one territory can be leveraged to the advantage of an underpowered scheme in another. We’ll see the mirror image of this sort of thing in our next installment (LASZLO).

FERRARI, the dominant-discourse avatar, has expelled LASZLO, the counter-discourse avatar, from the semiosphere — and out-maneuvered RICK, the semiosphere’s antihero avatar, in the bargain. As Rick leaves, Ferrari picks up his fly swatter and swats at a fly. Utter triumph!

Next CASABLANCA CODES series installment: LASZLO.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.