Ilsa

This is the fourth of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

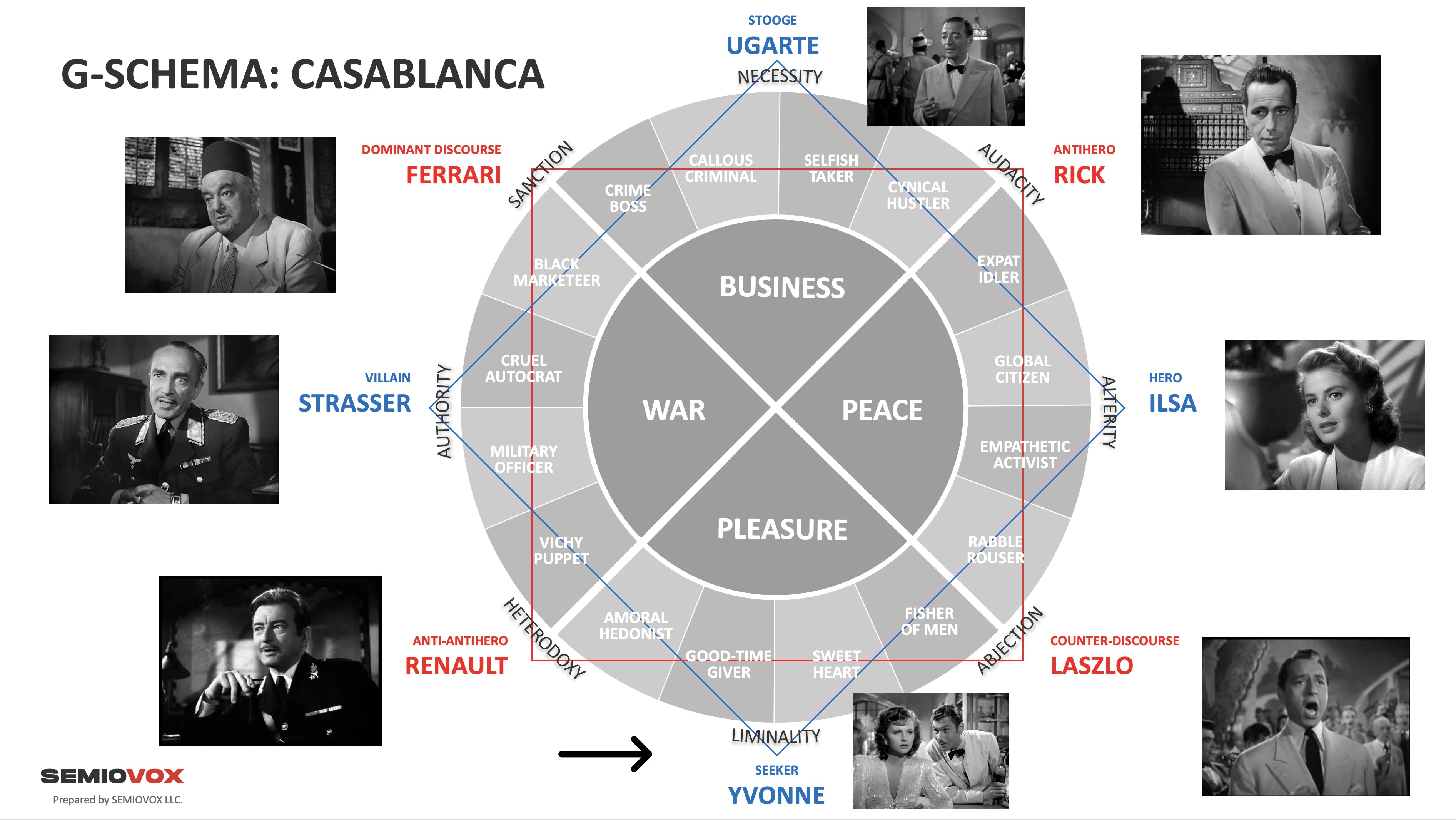

So far in this series, we’ve identified FERRARI as the Casablanca semiosphere’s dominant-discourse paradigm, LASZLO as its counter-discourse paradigm, and STRASSER as its villain paradigm. All of which is charted out via the Casablanca G-schema reproduced here.

We turn now to the Casablanca semiosphere’s hero(ine) paradigm… the second of four vertices that we’ll explore on our G-schema’s second semiotic square.

The hero paradigm of any G-schema governs the territory diametrically opposed to the territory governed by the villain paradigm. As was explored in the previous installment, the villain paradigm STRASSER is central — structurally centered, that is to say; it’s not a hybrid paradigm — to the semiosphere’s WAR territory. WAR, in this case, is one of this semiosphere’s “dominant discourse” territories (the other being BUSINESS); a G-schema’s villain paradigm always represents the dominant discourse’s authority. Conversely, the hero paradigm is central to this semiosphere’s PEACE territory, which is diametrically opposed to the WAR territory. The hero represents alterity — the quality or state of being radically alien to a particular (in this case, the villain’s) cultural orientation.

Dialing “down” from the Casablanca G-schema’s paradigm level (the eight characters listed around the chart’s outermost edge) to its thematic level (the sixteen thematic complexes identified here), we find diametrically opposing the “villain” complex MILITARY OFFICER the “hero” complex GLOBAL CITIZEN; meanwhile, diametrically opposing the “villain” complex CRUEL AUTOCRAT is the “hero” complex EMPATHETIC ACTIVIST.

So… which Casablanca character best embodies these [Casablanca semiosphere-specific; different semiospheres require different heroes] heroic qualities?

Ilsa Lund, an idealistic young Norwegian character, is at first presented to us as a globe-trotting mystery woman: Rick’s lover in Paris, who dumped him when the Nazis arrived; she turns up in Casablanca on the arm of Laszlo. Later, we’ll discover that she is an empathetic activist tormented by the necessity to choose supporting the leader of the anti-fascist cause over true love. The hero paradigm, for the semiosphere Casablanca, is: ILSA.

In this installment, we’ll examine in depth the thematic complexes governed by the ILSA paradigm. Let’s pause, though, for a few notes about the actress who portrays Ilsa Lund.

Ingrid Bergman (1915–1982) began her acting career in Sweden and Germany. She made her Hollywood début three years before co-starring with Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca (1942). She would go on to earn Oscar nominations for her performances in For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), Gaslight (1944), The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), and Joan of Arc (1948); and she’d win Oscars for Gaslight (1944) and Anastasia (1956). Bergman would also appear in three Hitchcock movies. Late in her career she’d win another Oscar, for Best Supporting Actress, for Murder on the Orient Express. Alongside Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Audrey Hepburn, and Greta Garbo, she is considered one of Classic Hollywood’s most influential female screen legends.

I’ve suggested that Casablanca is overrated; Bergman felt the same way. “I made so many films which were more important,” she’d lament, “but the only one people ever want to talk about is that one with Bogart.” Late in life, when asked to explain why the movie had become such a cultural touchstone, she’d say: “I feel about Casablanca that it has a life of its own. There is something mystical about it. It seems to have filled a need, a need that was there before the film, a need that the film filled.”

The structural underpinning of the extraordinary Casablanca mystique is precisely what SEMIOVOX’s series investigates.

GLOBAL CITIZEN

The stunning Miss Ilsa Lund enters Rick’s Café Americain on the arm of the famous resistance leader Laszlo, an older man. Is she his mistress, he her sugar daddy? That’s our initial impression.

This impression is, we’ll eventually discover, a carefully calculated one. Ilsa’s marriage to Laszlo is a closely kept secret, lest Laszlo’s enemies seek to manipulate him via threats to her. Perhaps this is why Ilsa can so often seem cold and distant; when out in public with Laszlo, she must (heroically) play the thankless role of a cynical, self-interested “adventuress.”

We don’t know any of this yet. Our first impression of Ilsa was influenced by the following dialogue between Rick and Renault, who have just been discussing women cynically, and who have furthermore made a bet about whether Laszlo will escape from Casablanca. Renault doesn’t believe that he’ll succeed.

RENAULT: No matter how clever he is, [Laszlo] still needs an exit visa, or I should say, two.

RICK: Why two?

RENAULT: He is traveling with a lady.

RICK: He’ll take one.

RENAULT: I think not. I have seen the lady. And if he did not leave her in Marseilles, or in Oran, he certainly won’t leave her in Casablanca.

RICK: Maybe he’s not quite as romantic as you are.

Rick doesn’t know who Laszlo’s female companion is, yet. In his world-weariness, he assumes the two must be using one another; he certainly no longer believes in romantic love.

At first, we’re led to believe that Rick may be correct about Ilsa. Despite her innocent-looking face, the young Norwegian certainly seems to get around. Using a regrettable descriptor for Sam (Dooley Wilson), she remarks casually to Renault: “Captain, the boy who is playing the piano, somewhere I have seen him.” It seems she is a habituée of night clubs across the continent.

Sam wheels his piano to Ilsa’s table, and their conversation confirms that they know each other better than she’s let on.

Ilsa directs Sam to play “some of the old songs,” then asks him about Rick. Sam’s cheerful face grows anxious and evasive; his apparently tough, even hardboiled employer and friend, it appears, must be protected from Ilsa’s malign influence. Is she a femme fatale? She is amused by his clumsy efforts in this regard.

ILSA: Does [Rick] always leave so early?

SAM: Well… he’s got a girl up at the Blue Parrot. He goes up there all the time.

ILSA: You used to be a much better liar, Sam.

SAM: Leave him alone, Miss Ilsa. You’re bad luck to him.

This dialogue contributes to our sense that Ilsa is nothing but trouble. Like Mary Astor’s character in The Maltese Falcon, for example, she may look sweet and innocent, but she’s devilish.

The film noir-style repartee grows saltier once Rick and Ilsa are reunited.

RENAULT: I can’t get over you two. She was asking about you earlier, Rick, in a way that made me extremely jealous.

ILSA (to Rick): I wasn’t sure you were the same. Let’s see, the last time we met —

RICK: It was La Belle Aurore.

ILSA: How nice. You remembered. But of course, that was the day the Germans marched into Paris.

RICK: Not an easy day to forget.

ILSA: No.

RICK: I remember every detail. The Germans wore gray, you wore blue.

Reacting to this jibe, Ilsa suddenly shifts into another tonal register — one we’ll come to understand, later, as that of the thematic complex EMPATHETIC ACTIVIST. She says: “Yes, I put that dress away. When the Germans march out, I’ll wear it again.” The wise-cracking dame reveals her steely resolve, if only for a brief moment.

On their way out of the club, when Laszlo asks of Rick, “What sort is he?” she responds airily enough: “Oh, I really can’t say, though I saw him quite often in Paris.”

A flashback to Paris reveals that Ilsa and Rick (“Richard,” here) enjoyed a boozy, sexy, sophisticated relationship, one that required Richard not to ask any questions about Ilsa’s past.

RICK: Who are you really? And what were you before? What did you do and what did you think? Huh?

ILSA: We said “no questions.”

RICK: Here’s looking at you, kid.

Ilsa wants Richard to flee Paris, because he’s on the invading Germans’ “blacklist” (his words). Unlike him, she speaks German well enough to understand the commands that the Gestapo are broadcasting via loudspeaker; another sign of her worldly sophistication. He’s willing to do so, as long as she goes with him. Which she seems willing to do, though at the last minute she becomes evasive and squirrely: “I, uh, I have things to do in the city before I leave. I’ll meet you at the station, huh?”

Richard impulsively, tipsily, semi-jokingly proposes to Ilsa. She is evasive. This mystery woman, it seems, must forever remain on the move, a solo operator. But this noir-ish impression of Ilsa is complicated by her sincere tears, and her earnest declaration that “I love you so much, and I hate this war so much.”

Our impression of Ilsa is now a more complicated one. Like Richard, we want to know: Who is she really? What was she before? What did she do and what did she think?

Sneaking out of her hotel room that night, without Laszlo’s knowledge, Ilsa returns to the Café Americain, intending at last to reveal the answer to Richard’s questions. She finds him drinking alone, awash in self-pity and anger. We’ll look more closely at this scene in the following section of this installment, as well as in the RICK installment.

The next day, in Strasser’s office, Ilsa continues to behave like a cold adventuress.

LASZLO: Well, perhaps I shall like it in Casablanca.

STRASSER: And Mademoiselle?

ILSA: You needn’t be concerned about me.

In the bazaar, Rick offers Ilsa a valid excuse for having ditched him in Paris, and suggests that he’s ready and willing to resume their affair.

RICK: Did you run out on me because you couldn’t take it? Because you knew what it would be like, hiding from the police, running away all the time?

ILSA: You can believe that if you want to.

RICK: Well, I’m not running away any more. I’m settled now, above a saloon, it’s true, but… walk up a flight. I’ll be expecting you.

lsa turns her head away.

RICK: All the same, someday you’ll lie to Laszlo. You’ll be there.

ILSA: No, Rick. No, you see, Victor Laszlo is my husband… and was, even when I knew you in Paris.

Ilsa’s big reveal — and what we’ll learn later, that Laszlo had been arrested by the Gestapo and supposedly killed when she’d met Rick in Paris — requires us to revise our initial impression of this character. If Rick is stunned by it, then so are we.

In our Casablanca G-schema, the complex GLOBAL CITIZEN is adjacent to the complex EXPAT IDLER. Why do these themes belong in the PEACE territory? Because the ability to move from country to country, to leave your small world behind for a larger world, is not something we should take for granted. In fact, it’s an almost utopian achievement, the closest humankind will likely ever come to an H.G. Wells-type one-world utopia. Among the many reasons to oppose fascism, Casablanca — the plot of which concerns refugees, borders, travel papers — places the utmost emphasis on the freedom of movement.

As our Casablanca G-schema shows, the “hero” thematic complex GLOBAL CITIZEN is diametrically opposed to the “villain” complex MILITARY OFFICER. Whereas Strasser, the military officer, is driven to strategize and issue commands, Ilsa is driven to help establish a utopian world in which strategy is unnecessary, and in which no one must obey commands. Strasser seeks to cross borders forcefully; Ilsa wishes to do so freely and peacefully. Strasser’s tonality is authoritative, he seeks to dominate; Ilsa’s seeks only to persuade.

Rick, the expat idler who can’t return to the United States, moves from country to country smuggling weapons to anti-fascist underdogs, and hanging around in nightclubs. Ilsa, too, we now discover, has spent years on the move from country to country. She is a global citizen struggling to keep those borders open… by assisting Laszlo in his peripatetic crusade to rouse anti-Nazi resistance wherever they go. Her commitment to this cause is so profound that she was willing to abandon Rick, whom she loves in a romantic way that she doesn’t love her husband.

Revisiting Ilsa’s first scene, when she asks Sam to play “As Time Goes By,” a song that she and Rick strongly associate with their time together in Paris, we now realize that this is a self-lacerating moment. The seemingly cold and self-involved global citizen is briefly permitting herself to re-experience emotions that, as an activist, she cannot and will not permit herself ever again to experience.

If what I’ve written seems to suggest that Ilsa is merely pretending to be a [jet-setting, femme fatale] citizen of the world, in order to prevent Laszlo’s enemies from attempting to get to him via her, that’s not the case. She is doing this, but at the same time Ilsa actually is a citizen of the world — in an idealistic, even utopian way. The downside of which is a tendency to prioritize idealistic love for humanity and freedom over romantic love for individuals and local attachments. Both Laszlo and Ilsa wrestle with this problem….

EMPATHETIC ACTIVIST

Ilsa’s first line in the movie, uttered shortly after she and Lazlo enter the Café Americain, is: “Victor, I… I feel somehow we shouldn’t stay here.”

Ilsa has spotted Sam, and realizes who the club’s owner is. She wishes to leave, we’ll later discover, because it took every ounce of her willpower to abandon Rick in Paris when she learned that Laszlo was in fact alive, wounded, and in need of her aid. In a movie replete with hardboiled types who care only for themselves, Ilsa cares nothing for herself. Her passion for Laszlo’s cause, and warm admiration for him (as a good man and important anti-fascist leader, less so as a husband) are at odds with her deep attraction to and true love for Rick.

If she sees Rick again, will she be able to go on? This question haunts her.

Later that night, Ilsa attempts to explain her situation to Rick. She wants to tell him a story, she says.

ILSA: It’s about a girl who had just come to Paris from her home in Oslo. At the house of some friends she met a man about whom she’d heard her whole life, a very great and courageous man. He opened up for her a whole beautiful world full of knowledge and thoughts and ideals. Everything she knew or ever became was because of him. And she looked up to him and worshipped him with a feeling she supposed was love.

Rick doesn’t buy any of this, for now. But for us, it explains the origins of Ilsa’s progressive activism… and why her activism cannot be untangled from her feelings about Laszlo. She doesn’t love Laszlo, exactly — but no one has ever (or will ever) been more inspiring to her. Because she believes in Laszlo and his cause, she has sacrificed true love for the opportunity to go on supporting him, which involves pretending to love him as he loves her.

When Ferrari offers to help Ilsa escape on her own, she refuses:

ILSA: We are only interested in two visas, Signor.

LASZLO: Please, Ilsa, don’t be hasty.

ILSA: (firmly) No, Victor, no.

She can’t bring herself to say that she loves him, in this scene, but she remains loyal.

ILSA: But, Victor, if the situation were different, if I had to stay and there were only a visa for one, would you take it?

LASZLO (not very convincingly): Yes, I would.

ILSA: Yes, I see. When I had trouble getting out of Lille, why didn’t you leave me there? And when I was sick in Marseilles and held you up for two weeks and you were in danger every minute of the time, why didn’t you leave me then?

LASZLO: I meant to, but something always held me up. I love you very much, Ilsa.

She smiles again.

ILSA: Your secret will be safe with me. Ferrari is waiting for our answer.

Later, back at Rick’s Café Americain, when Laszlo leads the crowd in singing “La Marseillaise” (see LASZLO installment in this series), the look on Ilsa’s face speaks volumes. She is moved by his ability to rouse resistance against fascism, and awed by his courage… but deeply worried that he will get himself captured and/or murdered.

Before she sings along with “La Marseillaise,” Corinna Mura sings “Tango Delle Rose”: “Pick me. My life is like a flower. It blossoms early and soon dies. My heart is for you alone.” The songs represent the two contrasting, sometimes conflicting aspects of the paradigm ILSA.

When Strasser approaches her, she displays her fierce courage and commitment to protecting and supporting Laszlo. As previously discussed, in the STRASSER installment in this series, the Princess Leia/Grand Moff Tarkin scene in Star Wars is an homage to this.

STRASSER: Mademoiselle, after this disturbance it is not safe for Laszlo to stay in Casablanca.

ILSA: This morning you implied it was not safe for him to leave Casablanca.

STRASSER: That is also true, except for one destination, to return to occupied France.

ILSA: Occupied France?

STRASSER: Uh huh. Under a safe conduct from me.

ILSA (with intensity): What value is that? You may recall what German guarantees have been worth in the past.

STRASSER: There are only two other alternatives for him.

ILSA: What are they?

STRASSER: It is possible the French authorities will find a reason to put him in the concentration camp here.

ILSA: And the other alternative?

STRASSER: My dear Mademoiselle, perhaps you have already observed that in Casablanca, human life is cheap. Good night, Mademoiselle.

It’s worth mentioning, here, the scene between Rick and the young Bulgarian refugee, Annina. Her story parallels that of Ilsa’s, though at the moment Rick can’t see that. Still, his sympathy for her — and effort to help her — is part of his “conversion” process.

Bitter that Ilsa never loved him the way that Annina loves her husband (or so he believes), Rick fails to understand how Annina’s story parallels Ilsa. Though Ilsa does love him, she was willing to make an enormous sacrifice in order to do what she knows is the right thing.

Like Annina, Ilsa is “so much older,” in important respects, than the man she loves.

Just as Ilsa had feared, when she first spotted Sam in Rick’s nightclub, Laszlo has become aware that she and Rick were lovers in Paris — when he was in a concentration camp, and reported killed. Laszlo is willing to forgive and forget; Ilsa, however, doesn’t want to discuss it — because doing so will eventually lead her to tell Laszlo the truth. She doesn’t love him.

After Rick tells Laszlo to ask Ilsa why he won’t sell the letters of transit to them, Laszlo gently broaches the subject.

LASZLO: Ilsa, I —

ILSA: — Yes?

LASZLO: When I was in the concentration camp, were you lonely in Paris?

Ilsa cannot look at him.

ILSA: Yes, Victor, I was.

LASZLO: I know how it is to be lonely. Is there anything you wish to tell me?

ILSA: No, Victor, there isn’t.

LASZLO: I love you very much, my dear.

Again, Ilsa can’t bring herself to tell Laszlo that she loves him. (Her response to him will be echoed in Han Solo’s famous response to Princess Leia’s “I love you” moment.)

ILSA: Yes. Yes, I know. Victor, whatever I do, will you believe that I, that —

LASZLO: — You don’t even have to say it. I’ll believe.

After this wrenching scene, Ilsa returns to the Café Americain, hoping that she can persuade Rick to give her the letters of transit. She’ll appeal to his anti-fascist fervor, and if that fails she’ll remind him of how much he used to love her. Will either ploy succeed?

ILSA: I know how you feel about me, but I’m asking you to put your feelings aside for something more important.

RICK: Do I have to hear again what a great man your husband is? What an important cause he’s fighting for?

ILSA: It was your cause, too. In your own way, you were fighting for the same thing.

RICK: I’m not fighting for anything anymore, except myself. I’m the only cause I’m interested in.

ILSA: Richard, Richard, we loved each other once. If those days meant anything at all to you -—

RICK: — I wouldn’t bring up Paris if I were you. It’s poor salesmanship.

ILSA: Please. Please listen to me. If you knew what really happened, if you only knew the truth —

RICK: — I wouldn’t believe you, no matter what you told me. You’d say anything now to get what you want.

Bitter and cynical, Rick still believes that Ilsa isn’t sincere.

Ilsa now tells Rick the truth about himself. Like Adorno, whose Minima Moralia entry “Tough baby” scoffs that the film noir “he-man” is over-compensating for his weakness, she pulls no punches. Written from 1944–49, and very much inspired by Hollywood movies of the early 1940s, Minima Moralia might perhaps have been referencing Bogart movies like Casablanca.

ILSA: You want to feel sorry for yourself, don’t you? With so much at stake, all you can think of is your own feelings. One woman has hurt you, and you take revenge on the rest of the world. You’re a — you’re a coward, and a weakling.

There are tears in her eyes.

ILSA: No. Oh, Richard, I’m sorry. I’m sorry, but, but you, you are our last hope. If you don’t help us, Victor Laszlo will die in Casablanca.

RICK: What of it? I’m going to die in Casablanca. It’s a good spot for it.

He turns away to light a cigarette, then back to Ilsa.

RICK: Now if you —

Ilsa is pointing a small revolver at him.

ILSA: — All right. I tried to reason with you. I tried everything. Now I want those letters. Get them for me .

RICK: I don’t have to. I’ve got them right here.

ILSA: Put them on the table.

RICK: No.

ILSA: For the last time, put them on the table.

RICK: If Laszlo and the cause mean so much to you, you won’t stop at anything. All right, I’ll make it easier for you.

He moves closer to her.

RICK: Go ahead and shoot. You’ll be doing me a favor.

Ilsa lowers the revolver. She turns and walks away from him.

As shown on the Casablanca G-schema, the “villain” thematic complex CRUEL AUTOCRAT is diametrically opposed by the “hero” complex EMPATHETIC ACTIVIST. Whereas Strasser the cruel autocrat deploys ideology in an effort destroy everyone else’s ability to imagine something better, to isolate them, and to make them feel alone and powerless to fight authoritarianism, Ilsa the empathetic activist offers no ideological justifications. Her secret weapon is her utter sincerity, her emotional honesty. She wears her heart on her sleeve.

ILSA: Richard, I tried to stay away. I thought I would never see you again, that you were out of my life.

Rick follows her and takes her in his arms.

ILSA: The day you left, if you knew what I went through! If you knew how much I loved you, how much I still love you!

In this moment of Ilsa’s defeat and profound despair, ironically, she finally gets through to Rick. He realizes, now, that Ilsa has been telling him the truth. She does love him, but she is deeply committed to Laszlo’s cause… and these are conflicting attachments. He’s ready to listen to her story, at last.

ILSA: It wasn’t long after we were married that Victor went back to Czechoslovakia. They needed him in Prague, but there the Gestapo were waiting for him. Just a two-line item in the paper: “Victor Laszlo apprehended. Sent to concentration camp.” I was frantic. For months I tried to get word. Then it came. He was dead, shot trying to escape. I was lonely. I had nothing. Not even hope. Then I met you.

RICK: Why weren’t you honest with me? Why did you keep your marriage a secret?

ILSA: Oh, it wasn’t my secret, Richard. Victor wanted it that way. Not even our closest friends knew about our marriage. That was his way of protecting me. I knew so much about his work, and if the Gestapo found out I was his wife it would be dangerous for me and for those working with me.

RICK: When did you first find out he was alive?

ILSA: Just before you and I were to leave Paris together. A friend came and told me that Victor was alive. They were hiding him in a freight car on the outskirts of Paris. He was sick, he needed me. I wanted to tell you, but I, I didn’t care. I knew, I knew you wouldn’t have left Paris, and the Gestapo would have caught you. So I… well, well, you know the rest.

RICK: Huh. But it’s still a story without an ending. What about now?

ILSA: Now? I don’t know. I know that I’ll never have the strength to leave you again.

Casablanca, in our analysis, has something profound to teach us about a story’s HERO paradigm. The hero must be strong — not only to oppose the villain, but to reconcile the conflicting magnetic attraction of the ANTIHERO and COUNTER-DISCOURSE paradigms. The characters representing these paradigms make powerful claims on the hero’s loyalty.

ILSA: I can’t fight it anymore. I ran away from you once. I can’t do it again. Oh, I don’t know what’s right any longer. You’ll have to think for both of us, for all of us.

RICK: All right, I will. Here’s looking at you, kid.

The Casablanca G-schema positions the “counter-discourse” thematic complex RABBLE ROUSER (governed by the paradigm LASZLO) adjacent to the “hero” complex EMPATHETIC ACTIVIST (governed by the paradigm ILSA). While Ilsa the global citizen is attracted to the rootless, nomadic Rick, Ilsa the empathetic activist belongs at the side of the utopian visionary Laszlo. When Ilsa tells Rick, “I don’t know what’s right any longer,” she’s expressing this sense of being torn in opposite directions. She leaves it up to Rick.

What Ilsa doesn’t realize — nor does the viewer — is that Rick actually is thinking for everyone now. The chess master must begin to move pieces around the board. Which entails deceiving Ilsa… and abandoning her, for a good reason. Just as she once did to him.

At the airport, once Rick reveals his true plan, Ilsa protests. She wants to stay with him.

RICK: Inside of us we both know you belong with Victor. You’re part of his work, the thing that keeps him going. If that plane leaves the ground and you’re not with him, you’ll regret it.

ILSA: No.

RICK: Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life.

Thanks to Ilsa’s intervention, Rick is no longer what Adorno calls a “tough baby.”

Next CASABLANCA CODES series installment: UGARTE.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.