Judge Smails

Judge Smails takes a golf ball to the crotch

This is the sixth installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

In this series’ second installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed (over the past 20+ years) in order to productively and insightfully map any product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s network of meaningfulness. In constructing each new G-Schema, I proceed in a tried-and-true fashion — the idiosyncratic methodology of which this series aims to demonstrate.

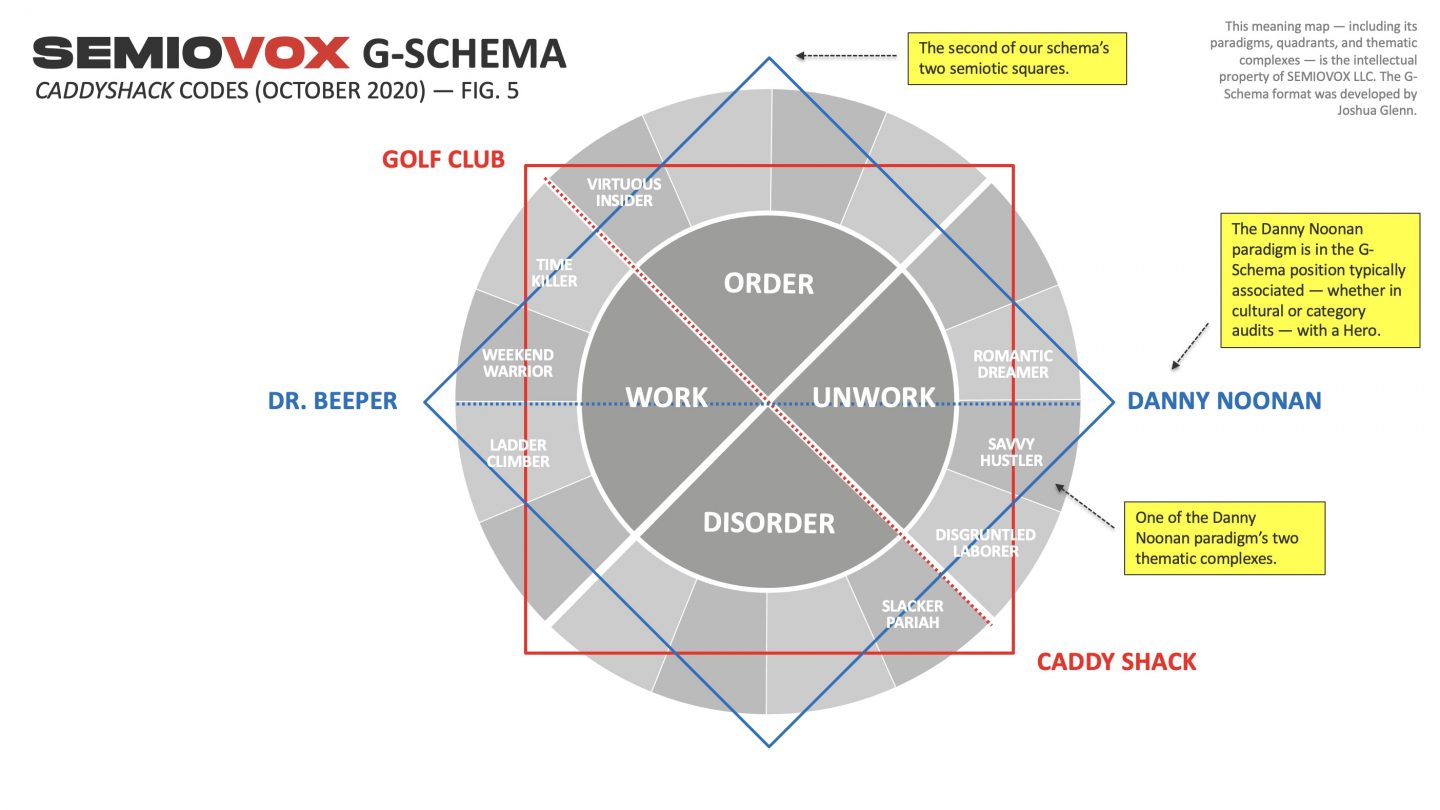

By the end of this series’ fifth installment, we’d arrived at the mapping stage illustrated in Fig. 5 (above). As you can see, we’ve now completed our analysis of two of this map’s four codes: Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack and Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan. (As explained in our second installment, a semiotic code is alway a binary opposition of a symbolic expression with its direct inversion, hence the “vs.” aspect of the codes described here.) In this post, we’ll begin the process of completing our second semiotic square — rendered in blue, in the G-Schema — by looking at the first term, Judge Smails, in this semiosphere’s third code: Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler.

Paradigm

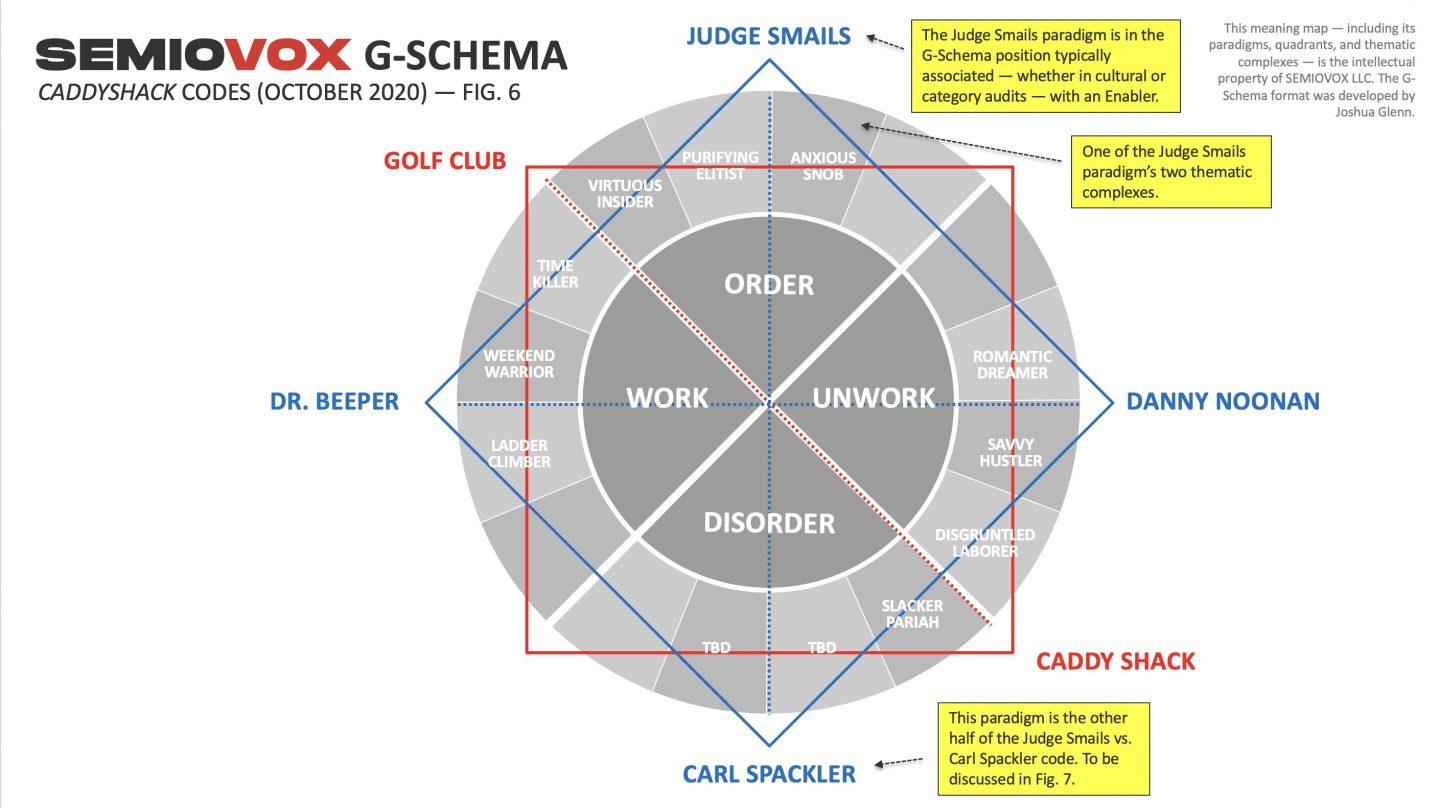

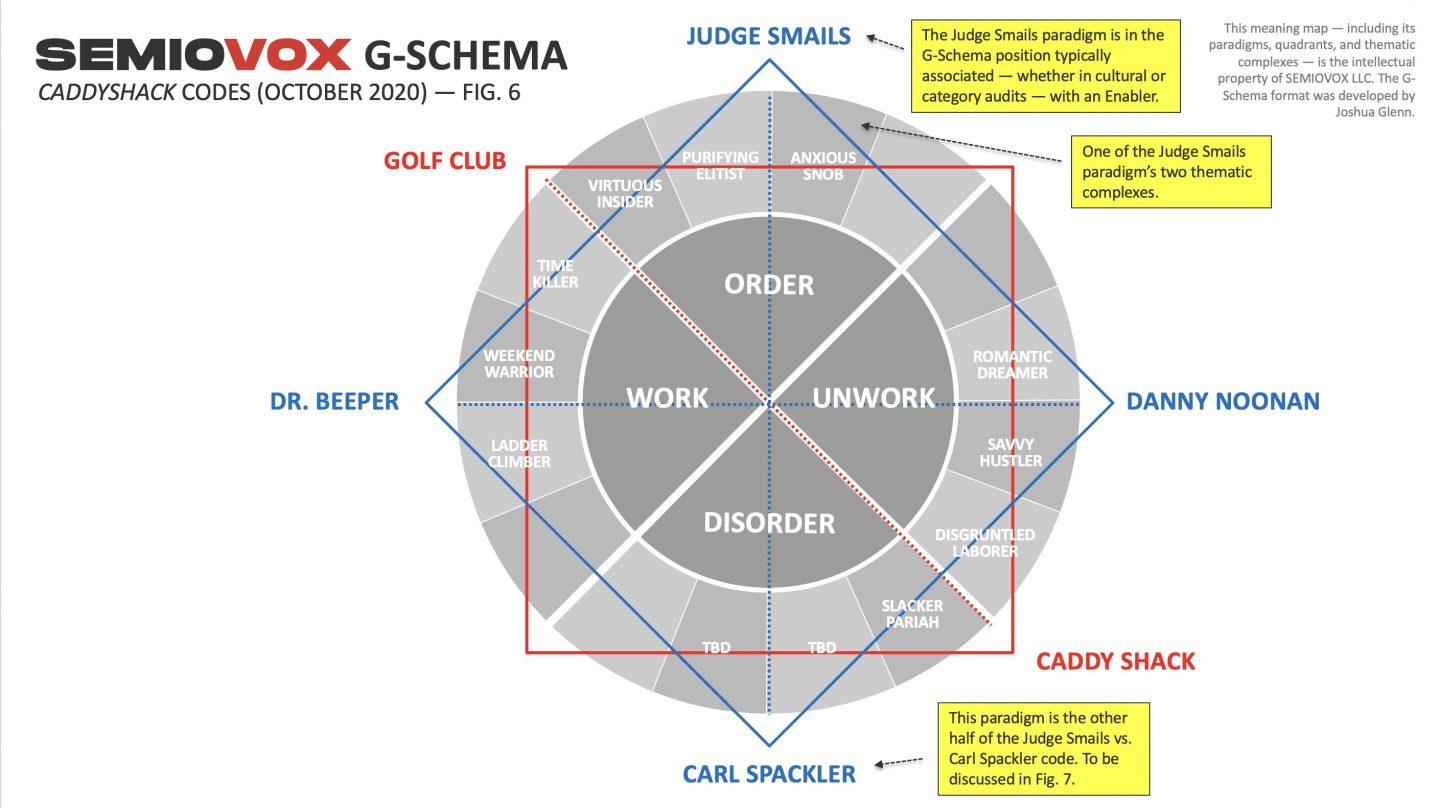

As Fig. 6 (below) indicates, according to my analysis the paradigm Judge Smails governs the Caddyshack meaning-map’s ORDER quadrant. According to Greimasians, the “meta-term” that emerges a posteriori from the opposition between a semiosphere’s unmarked term (i.e., the dominant discourse, according to our analysis; in this case, the Golf Club) and its marked term (the top right of our diagram; to be explicated later) is a “complex” one. Judge Smails is indeed a complex figure. Dogmatism and self-sufficient presumption are often associated with the complex meta-term; these grow out of deep-seated insecurity, a desperate effort to mediate between the semiosphere’s unmarked and marked terms. Note that Greimas suggested that this meta-term could be thought of as a utopian one, transcending the semiosphere’s main opposition; I disagree, though it’s certainly the case that within this semiosphere, Judge Smails “has it all.”

In psychological terms, following Gregory Bateson we can say that a semiosphere’s complex figure (at top center of a G-schema) is caught in a “double bind.” This figure can’t win. If intensified and prolonged, Bateson would have us understand (in a 1956 essay collected in 1969’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind), a double-bind situation can lead to a person becoming “a clown, a poet, a schizophrenic, or some combination of these.” Which brings us back to Judge Smails — played by Ted Knight, whose turn as the vain, bombastic, yet deeply insecure news anchor Ted Baxter on The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970–1977) won him two well-deserved Emmy Awards — is this semiosphere’s “complex” figure, a clown, and an avatar of what Lacan calls the socio-symbolic order.

Before we get into Lacan’s theory, let me just reiterate a sentiment that I’ve expressed before: Ted Knight’s performance makes Caddyshack, despite its obvious flaws, one of the all-time greatest comedy movies. In Chris Nashawaty’s book on the making of Caddyshack, we read that “beneath his confident gas-bag veneer, Knight’s Baxter was nothing more than a grown-up child — desperate for approval, easily wounded, and unwilling to come clean when he was wrong.” That goes for Smails, too. (And for the sitting US president, as I write this post.) It takes tremendous skill, on the part of an actor, to make such a character less villainous than pathetic, even slightly lovable; Steve Carrell’s Michael Scott is the only other example that comes to mind.

In order for a child to join society, according to Lacan, whose adaptation of Saussurean semiotics revolutionized Freudian psychoanalysis, he or she must first internalize the “big Other”: society’s rules and dictates. These are absorbed almost by osmosis, as part of accepting language’s rules. The symbolic order that helps shape our perceptions and control our desires is a social world of linguistic communication, intersubjective relations, knowledge of ideological conventions, and the acceptance of the law. This order is closely bound up, Lacan persuasively suggests, with the father, whose internalized voice is the superego, as well as with the “phallus.”

Judge Smails, as we’ll see, is a wannabe version of the father-superego-phallus construct; Knight’s performance helps us find this failure funny.

In my experience, the top-most vertex in a G-Schema represents not a semiosphere’s superego (that would be the top-left vertex, i.e., the primary term of the semiosphere’s master code; here, the paradigm Golf Club) but its ego. Which is not to suggest, of course, that a semiosphere is a human being with a psychic apparatus of its own. However, as Lacan helped us understand, in his own not entirely comprehensible way, a structuralist approach to psychology has a great deal to learn from structuralist anthropology… and vice versa.

The least understood aspect of the psyche is the ego — which is deformed, according to Freudian theory, warped by its inability to reconcile the id’s relentless instinctual drives with the superego’s nagging and preaching. The ego is an enabler, of sorts, trapped in a self-destructive pattern of trying to appease these two masters. The paradigms that turn up in a G-Schema’s top-vertex position, I’ve found, may appear confident and reasonable (the ego is all about projecting confidence and reasonableness) but in fact they’re faking it. So casting Ted Knight in this role was a stroke of genius. His ability to toggle back and forth between authoritarian bombast and cringing insecurity allows him to illustrate for his audience the ego’s deformity.

Adapting and building upon the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Judge Smails categorical proposition like so: “It must not be the case that Caddy Shack is not Golf Club.” The proposition Golf Club simply takes it for granted that Caddy Shack shares its values, ideas, and so forth. It is left to the propositions flanking Golf Club (and therefore “infected” by uncertainty) on our diagram to do the dirty work of preserving this illusion. We’ve talked about Dr. Beeper in another installment; here we’ll look at how a Judge Smails figure works, within a semiosphere, to prevent the dominant paradigm (here: Golf Club) of becoming aware of and subverted by the antiheroic proposition (represented here by Ty Webb).

A Fig. 6 (above) indicates, my analysis of the paradigm Judge Smails suggests that the two thematic complexes governed by this paradigm are Purifying Elitist and Anxious Snob. In this post, I’ll bring these complexes to life via a close analysis of the source codes (“signs”) native to each.

Purifying Elitist

In this series’ second installment, we analyzed the paradigm Golf Club’s thematic complex Virtuous Insider — which, as Fig. 6 (above) indicates, is adjacent to the paradigm Judge Smails’s thematic complex Purifying Elitist. According to the self-serving weltanschauung of the Golf Club’s members, their Bushwood membership offers evidence of their own WASPy virtue. Eager for us to understand that WASPdom’s self-congratulatory culture is flaccid, hypocritical, and corrupt, the creators of Caddyshack offer us the example of Judge Smails — whose self-defeating antics demonstrate that at some level he isn’t entirely persuaded that he truly deserves his privilege.

His deep-rooted lack of faith in his own bullshit helps explain that aspect of Smails’s character and behavior that we’ll analyze here — i.e., his obsession with border-patrolling Bushwood’s boundaries and, by extension, preserving his own elite status. Or vice versa.

In Smails’s very first scene, he spies a gopher tunneling on the golf course. The exaggerated expression of horror on Knight’s countenance (8:10) could serve as an illustration next to a definition of Purifying Elitist. For Smails, Bushwood is emblematic of the socio-symbolic order that he must defend; and any incursion into this sanctified space made by impure outside forces — whether gophers, ethnics, vulgarians, etc. — must be summarily dealt with. In this mission, he has appointed himself judge, jury, and executioner.

The gopher, according to Bushwood’s groundskeeper, has been driven into the golf course by the disruptive, nearby construction of a condominium complex; a glimpse of the construction project (8:27) reveals a sign advertising the Czervik Construction Co. Almost subliminally, we’re afforded some insight into the true source of Judge Smails’s outrage: The borders of his elite world of privilege are being threatened from outside, tunneled under even, by an ethnic upstart.

Are we reading too much into a brief glimpse of a business’s sign? Is Smails really racist, xenophobic, anti-Catholic, and so forth? Yes, he is. In a locker-room scene that follows not long after this one (17:25), Smails begins to tell a joke about “a Catholic, a Jew, and a colored boy” to one of his Bushwood cronies… who, laughing uproariously, turns out to be a (Protestant) bishop. If we didn’t already understand that the Bishop is a bigot, it’s made very clear (at 25:15) when he invites Danny Noonan to the church’s new youth center… then disinvites him once he learns that Noonan is a Catholic.

A moment later, Czervik shows up in the Bushwood Pro Shop, wearing tasteless clothes and spending money freely on his Asian business partner. Czervik makes an ethnic joke of his own, when he enters, warning the obviously un-Jewish Mr. Wang that the club doesn’t admit Jews — har har. (At least Czervik’s joshing is at the expense of the segregated Bushwood.) Smails, whose own outfit is supposedly more tasteful, looks on grimly. Not only does Czervik turn the tables on Smails, here — as we’ll see when we dig into the Anxious Snob thematic complex — but in a few minutes’ time he’ll accidentally fire a golf ball into the Judge’s groin. What’s with that?

As mentioned earlier, Lacan’s work elaborates language as a symbolic order that precedes and makes possible human subjectivity. (“Symbolic” is Lacan’s term for the way in which reality becomes intelligible and takes on meaning and significance, through words.) Importing Saussurean semiotics, as well as the semiotics-driven anthropology of Claude Levi-Strauss, into the domain of psychoanalysis, Lacan argues that the “order” of language is instituted through a symbolic articulation in precisely the same way that, in primitive (and modern) societies, paternal prohibition provides the conditions for human sociality — i.e., by repressively dictating desire and its limits. In order to assume his or her place in society, a child must submit both to the nom du père (authority) and the non du père (repression of desires); in thus submitting, a child is symbolically castrated. The subject’s “phallus,” which for Lacan represents primordial being in all its fecund possibility, is cut off; to be a subject in society, therefore, is to be fractured.

Do we have to bring Lacan and Kristeva into our discussion of Caddyshack? you ask. We don’t. However… Lacan and Kristeva’s theories, particularly when it comes to the Judge Smails character, is undeniably pertinent in grokking the tensegrity — that is, the dynamic tension — of the relation between our Caddyshack meaning map’s ORDER and DISORDER quadrants. Plus, the movie’s otherwise juvenile castration gags become highly relevant and meaningful when viewed through the lens I’ve just tried to explain.

In this series’ earlier installment on the paradigm Caddy Shack, I brought up Julia Kristeva’s post-Lacanian theory of “abjection.” In abjection, the Lacanian fractured subject confronts (unconsciously) what he or she must exclude or expel in order to maintain their inherently unstable identity. Women, homosexuals, immigrants, members of ethnic and religious minorities, and others who are perceived as socially marginal, or refusing cultural assimilation, become troubling figures to the symbolically castrated Lacanian subject. Which brings us back to Judge Smails.

I seriously doubt that Harold Ramis was familiar with French theory — as mentioned, Kristeva’s Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection appeared in 1980, the same year as Caddyshack — but it’s fascinating to see how often Judge Smails is figuratively castrated during this movie. And not always figuratively: At 22:02, Czervik’s wayward golf ball literally hits Smails’s nuts.

Smails, who perceives himself as Bushwood’s bearer of the nom du père and non du père, is a fervent no-sayer. No to the gopher, no to Czervik, no to the caddies’ antics, no to Danny Noonan’s game efforts to hustle his way into the Establishment, and no in particular to his nose-picking, weed-smoking grandson Spaulding’s bad habits. Symbolic order-wise, Spaulding is un-castrated, i.e., following his own desires willy-nilly; Smails takes it upon himself to fracture his grandson’s phallus. In this series’ second installment, we reviewed Smails’s rebuke to the greedy Spaulding, which could have been ventriloquized by Lacan, “You’ll get nothing — and like it!” Here, we should also mention Smails’s rebuke when Spaulding, at the Fourth of July gala, ravenously enquires whether Dr. Beeper’s companion is planning to eat her fat (29:59). Also, at the yacht club, in the midst of christening his new sloop, Smails barks, “Spaulding, get your foot off the boat!” (55:28). He’s got the non du père down pat — yet Smails is a failed authority figure.

Judge Smails and his wife, Pookie, struggle to police Bushwood’s socio-symbolic order — which, by extension, is America’s socio-symbolic order. Theirs is a Sisyphean task; in every single Caddyshack scene involving this husband-and-wife duo, borders are transgressed, the unsullied is sullied. At the Fourth of July gala, their dinner party is interrupted by Czervik’s antics; when they hit the dance floor (36:07) and discuss the interloper, they literally stick their noses into the air in disgust. Czervik then disrupts the dance by bribing the band to play a disco song, and cuts in on Mrs. Smails — making outrageous jokes, which we’ll discuss later on. “You’re no gentleman!” fumes Smails (36:41). “I never want to see that man here again!” Czervik is Bushwood’s abject; Smails is obsessed with expelling him.

The caddy’s tournament is, oddly, a big deal for Smails. As we’ve seen, Bushwood conflates skill at golf with personal virtue — i.e., like a Protestant’s worldly success, according to Weber’s analysis, an impressive golf handicap somehow demonstrates that one deserves one’s privilege. The tournament’s trophy is displayed to us with a medieval joust-like trumpet blast (39:36), and Smails follows Noonan’s progress every step of the way… even swatting D’Annunzio’s pesky brother for shouting “NNNOONAN” in a (since then, much-imitated) effort to throw Danny off his game (41:07). The caddies, too, are Bushwood’s abject; an abject that sabotages from within. No one is more overjoyed when Danny wins the trophy than Smails. It’s almost sweet… except that we mistrust Smails’s motives.

The swimming pool scene is a particularly abject moment, as we’ve seen in this series’ third installment. The horrified “O” of Mrs. Smails’s mouth gets larger and larger, from the first moment that she sees the caddies frolicking in the pool (47:13) to the moment at which she spots the “turd” in the water… at which point Pookie actually resembles Munch’s The Scream. Cut to Judge Smails overseeing white-suited figures: “I want the entire pool scrubbed, sterilized, and disinfected!” (48:14) He is at his most bombastic, at moments like this, striking a pose as abjection’s most implacable foe.

The free-floating candy bar in the pool could be likened to a castrated phallus, I suppose, but that’s a stretch. No need to make an effort to locate castration jokes in Caddyshack. Recall the sloop-christening scene at the yacht club, for example. After Elihu delivers himself of a Kipling-lite, supposedly wry poem about how a (WASPy) fellow ought to handle himself (stoically) in moments of adversity, Pookie strikes the phallic bowsprit of the Flying WASP with a champagne bottle… snapping the bowsprit off (56:00). Shortly thereafter, Czervik’s (large, tasteless) motor-powered yacht anchor plunges through Smails’s (small, tasteful) vessel, sinking it (58:26). Suffice it to say that Smails does not handle his adversity with stoicism.

Try as he might, Smails cannot prevent his socio-symbolic order from being sabotaged. Even once he returns to his own home, he finds Noonan in his bedroom with Lacey. Outraged — and perhaps jealous, since we infer that the WSPy Elihu and Pookie rarely couple — Smails snatches up yet another phallic symbol, a golf club, and pursues Danny (1:00:00). In his priapic rage, Smails smashes up his bedroom and batters a hole in the bathroom door; the message — that Smails’s obsession with order is more disruptive to the status quo he seeks to defend than anything else — is crystal-clear. And what does poor Smails see when he peeks into the bathroom (at 1:00:37)? His naked wife and a nearly naked Noonan exchanging admiring glances.

PS: Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, in which another toxic male hacks a hole in a door and peers through it menacingly — was also released in 1980. It might prove interesting to trace unexpected parallels between these two movies… but we’ll have to put that off for another time.

When next we see Judge Smails, he’s in what appears to be his office — striking a Faustian bargain with Noonan. Alternately bullying and flattering Noonan, he says things like, “I think you can still become a gentleman some day… if you understand and abide by the rules of decent society” (1:07:45). His non du père tactics aren’t working with Noonan, so here Smails is in full-blown nom du père mode. He pontificates, preaches, and bloviates: “I’ve sentenced boys younger than you to the gas chamber. Didn’t want to do it. But I… owed it to them.” (1:08:01) Only Ted Knight could pull this off. Finally, he offers Noonan the college scholarship in exchange for Noonan’s loyalty. He has, or so he believes, converted a saboteur into a gentleman.

There are two or three additional moments where Smails’s obsessive need to preserve the elitist purity of his world runs up against various saboteurs. At 1:10:05, Smails tells Czervik, “You have worn out your welcome at Bushwood, sir!” And also: “I guarantee you’ll never be a member here.” Unperturbed, Czervik both insults Bushwood and threatens to purchase it — which precipitates their scuffle, and following that, the money match. On the day of the money match, Czervik and Ty Webb violate the sanctity of the golf course — an above-ground version of what the gopher is doing below — by driving Czervik’s gaudy ’64 Rolls Royce Silver Cloud III convertible directly to the first tee (1:19:58). A flustered Smails demands that Ty drive it away, to no avail; Ty is the passenger, not the driver. And as we know, Carl Spackler will in the movie’s final scene blow up the entire golf course.

That which we repudiate, as Kristeva warned, always threatens to return. There’s a timely lesson here for America’s Republicans, of course. But there’s also a lesson for complacent liberals who can only vaguely comprehend the fact that (to quote Slate’s Lili Loofbourow), “Joe Biden still may win the presidency, sure. But a bigger proportion of the country than we thought is fine with things as they are. And they want more of it.” Each of us struggles in vain to fortify our porous borders against abjection.

Let’s move on, now, to the Judge Smails thematic complex Anxious Snob.

Anxious Snob

Judge Smails isn’t merely a purifying elitist; he is also an anxious snob. His need for others to demonstrate the proper respect for Bushwood’s customs, and for his own (inherited) social status, is unrelenting, all-consuming.

Smails’s fanatical devotion to keeping up appearances is evident from the beginning. He rolls into Bushwood in a 1972 Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow I — a vehicle that communicates wealth and status without being vulgar. As he changes into his golfing togs, he complains to the attendant Porterhouse about the wax build-up on his cleats, and gives him explicit instructions on how to remedy the situation (16:37). At the Fourth of July gala dinner, he is inordinately proud of his ceremonial jacket, the meaning and function of which he bores Lacey with (30:14). At the yacht club, he and Pookie demand that everyone gather around as they portentously christen their new sailboat. In his own home, a jacketed butler bears a massive silver tea set. His outfits — at the office, in the club, on the course — are impeccable.

All of this preppie peacockery masks a deep-seated insecurity, however. There’s an awkward moment in the Bushwood pro shop when Czervik, who is himself dressed eccentrically, clownishly — mocks what passes for preppie chic. “You buy a hat like this,” he says, pointing to a rainbow-striped, lightweight fedora, “I bet you get a free cup of soup!” (18:34) Humiliated, Smails flings off his own striped fedora and flees the scene. PS: Smails’s fedora has since become a fetish object, highly prized by golfers.

PS: A 2016 Medium essay by “Miles Gloriosus” uses Judge Smails as a prime example of the alazon, an ancient comedic archetype. The alazon is a braggart, an authority figure who acts like he knows everything. In the Trump era, according to “Miles Gloriosus,” this figure is no longer funny.

Smails’s status anxiety is also very much tied up with his own (middling) prowess at golf. As mentioned a few times in this series, for Smails — and Bushwood generally — one’s low golf score is proof of one’s elect status. Which is why Smails and his golfing buddies — Dr. Beeper and the Bishop — invariably lie about their scores to one another, and to themselves too. This also explains why it’s so troubling, to Smails, that Ty Webb won’t reveal his own score — and, in fact, dismisses the importance of keeping score. So Smails and Beeper are eager for the opportunity to compete against the elusive Webb. Although Smails often cheats when his fellow golfers aren’t looking — “Winter Rules,” “I was interfered with,” etc. — you can’t fake the first drive from the tee. Which is why he’s so persnickety about his swing, fiddling with his approach — to the exasperation of those behind him.

In Greimasian theory, the opposition between a semiotic square’s unmarked and marked terms is itself an unmarked opposition; the dominant discourse moves in mysterious ways, that is to say — controlling without seeming to do so. So we’ll rarely see the tension that drives Judge Smails to such extremes… but we can catch glimpses of it, for example when he’s golfing. It’s in these scenes where we sense how surprisingly, oddly insecure he is.

The scene (1:29:29 – 1:29:46) near the end of the money match, in which Smails ceremoniously calls for his special putter — “the old Billy Baroo” — which he caresses, and whispers to “(“Oh, Billy, Billy, Billy”), is a joy. Smails has made such a fetish of his own golf prowess that he literally possesses a fetish object — a kind of Excalibur, an implement that is somehow magical. Billy Baroo is one of the great movie objects; it’s a metaphor for Smails’s own character flaws — his hubris, his misplaced faith in golf’s significance.

Preserving Bushwood as a bulwark of elitism in a too-democratic world is supremely important to Smails. In fact, we learn that he and Webb’s father helped found the country club after WWII. “Ty — your father and I prepped together. We went to war together, we played golf together,” he murmurs to Webb, trying to dissuade the ace golfer from accepting Czervik’s offer to partner up in the proposed high-stakes money match (1:12:54). “We built this club, he and I. Let’s face it, son — some people simply do not belong.” He’s speaking in preppie code to Webb, invoking their families’ equally exalted social status; he assume that Ty is as much of a snob as he is. Of course, he’s wrong — but we’ll return to Ty Webb in a later installment.

Fun fact: Ted Knight dropped out of high school to enlist in the US Army in World War II. He was a member of A Company, 296th Combat Engineer Battalion, earning five battle stars while serving in the European Theatre.

During the money match, Smails has every intention of cheating. He selects Danny Noonan as his caddy — knowing that Noonan, to whom he has just promised the caddy scholarship, will be forced to look the other way. Which Noonan does, reluctantly. Later, when Czervik drops out of the game and Ty suggests that Danny should take his place, Smails reverts to his bullying ways — first suggesting that Noonan wouldn’t want to get involved “in something as illegal as this” (1:26:39), then coming right out and asking Noonan, rhetorically, “You don’t want that scholarship, do you?” (1:26:56) When Noonan stands up to to the bullying, Smails reverts to childish snark.

Smails, who’d bitterly resented being hurried (by Czervik) during his own golf game, and who’d defended Noonan against the younger D’Annunzio’s heckling during the caddy tournament, now heckles and hurries Noonan. Knight’s hilariously grotesque delivery (at 1:31:42) of the otherwise unremarkable line “Well? We’re waiting!” has deservedly become a meme. We glimpse D’Annunzio’s brother, whom Smails had swatted for this sort of poor sportsmanship during the caddy tournament, smirking behind him.

I’ll just add one final note, to this analysis of Judge Smails’s Anxious Snob thematic complex. As Fig. 6 indicates, this complex is adjacent to one of the meaning-map’s top-right paradigm’s two complexes — and it therefore offers us a clue as to the nature of that paradigm. As we moved clockwise through the ORDER quadrant, from Virtuous Insider to Purifying Elitist to Anxious Snob, we find a decrease in confidence and faith regarding the Golf Club’s status as exemplar of this semiosphere’s dominant discourse. Ideology works, as we’ve discussed previously, by persuading us to accept the way things are as natural, normal, and inevitable. To this end, it tends to “speak” calmly, with perhaps a hint of asperity or superciliousness when challenged; ideology is “cool.” Smails’s “hot” behavior lays bare the artifice.

So we can predict that our meaning-map’s top-right paradigm is going to be — at least in part — highly skeptical towards the claims of the Golf Club paradigm, which is to say the claims of this semiosphere’s “master code.” This figure will be one who — although not a rebellious hero figure like Noonan, nor a countercultural force like the caddy shack, nor an avatar of disorder like (as we’ll see, in this series’ next installment) Carl Spackler — embodies a cynical rejection of this semiosphere’s work-and-order ideologies. I noted, earlier, that the ego is an enabler — deformed by its inability to satisfy the competing demands of the superego and the id; if the Golf Club paradigm is this semiosphere’s supergo, then the top-right paradigm is its id. Knight’s tour de force performance, his contorted facial expressions and over-compensatory line deliveries, helps us understand the ego — which contorts and over-compensates, without ever finding relief.

There you have it: the first half of Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler, our Caddyshack meaning map’s third code. I’ve identified the paradigm Judge Smails’s contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. I’ve established not only what Judge Smails means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the character — but how this paradigm means what it means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts to facial expressions, clothing, mannerisms, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what Judge Smails signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

This series’ next installment will explore the second half of the Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler code: i.e., the paradigm Carl Spackler and its complexes.

Click here for the Carl Spackler post.