Dr. Beeper

Beeper reacts to being called "Dr. Frankenpuff"

This is the fourth installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

In this series’ second installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed in order to productively and insightfully map a product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s network of meaningfulness. In constructing each new G-Schema, I typically proceed in the same, tried-and-true, idiosyncratic way, the methodology of which this series aims to demonstrate.

☸

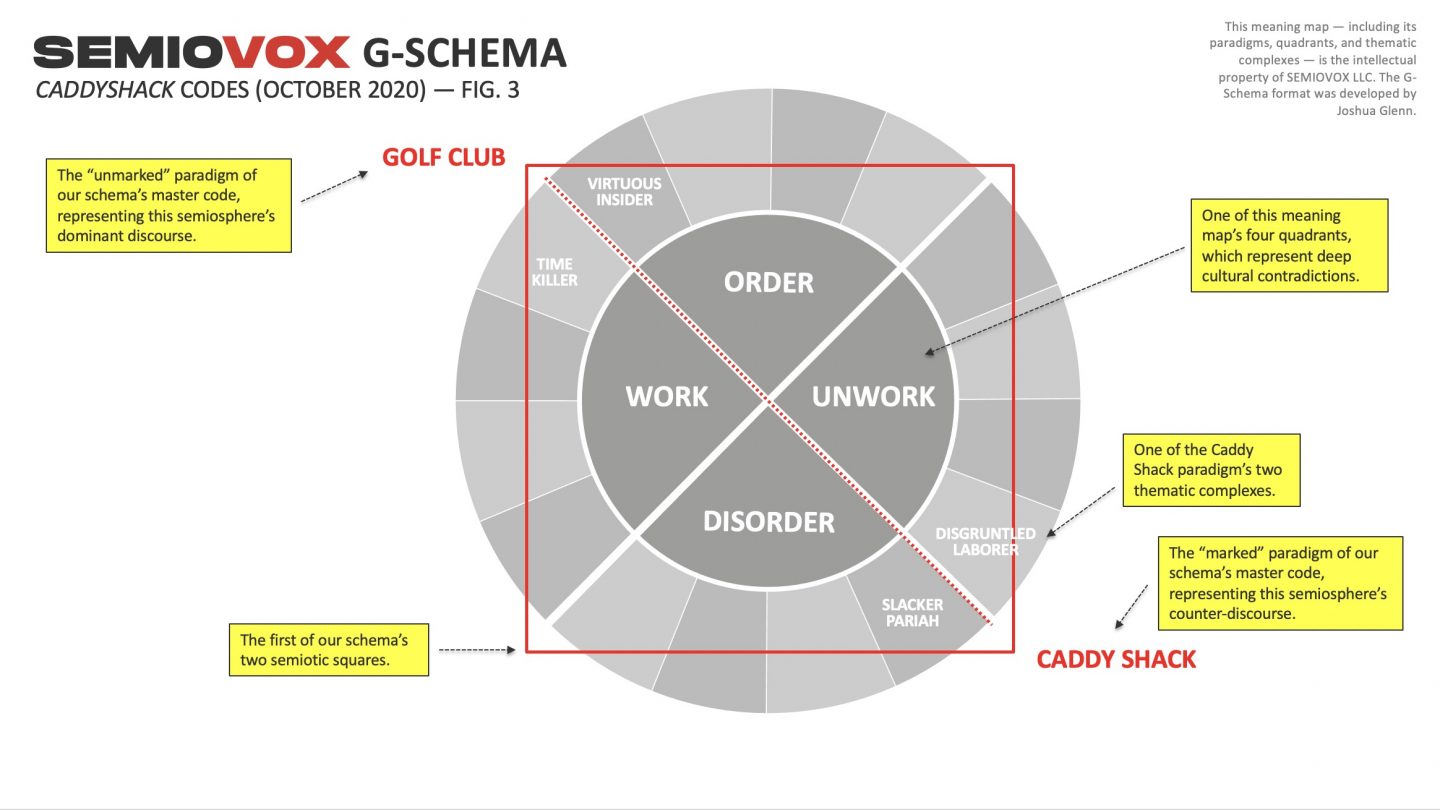

By the end of the third installment, we’d arrived at the mapping stage illustrated in Fig. 3 (below). Our schema’s master code, i.e., Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack, and its two paradigms’ thematic complexes are plotted. PS: Although naming a meaning-map’s quadrants is normally something I’d do last, for the sake of this exercise I’ve gone ahead and unveiled the four Caddyshack meaning-map quadrants.

Those readers familiar with the typical construction of a semiotic (or “Greimas”) square are no doubt puzzled by how I’ve proceeded. Instead of first naming the “positive” and “negative” terms (i.e., our square’s top left and top right vertices), thus forming an initial binary relationship between two contrary terms, I’ve instead first named the positive term (in this case, Golf Club) and our contradictory or “complex” term (in this case, Caddy Shack). Fredric Jameson is not wrong when he claims that the “neutral” term (bottom-left vertex) of a semiotic square is always trickiest to figure out; I always leave that paradigm for last. In my experience, though, a semiotic square’s “negative” term (top-right vertex) is almost as tricky. Over the years, I’ve come to realize that it’s best to triangulate our way towards the elusive “hermeneutic” code (formed by the paradigms at top right and bottom left) via a second semiotic square.

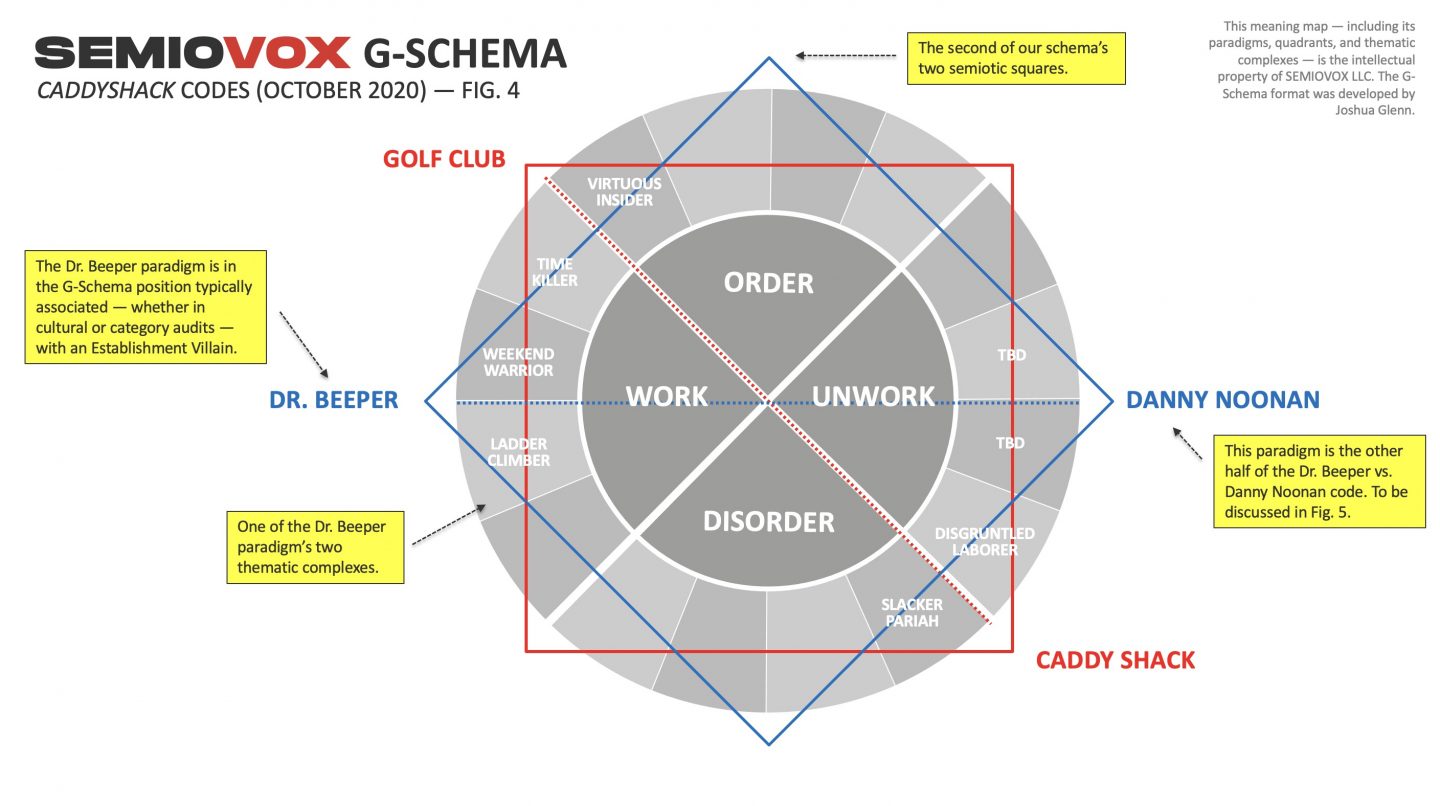

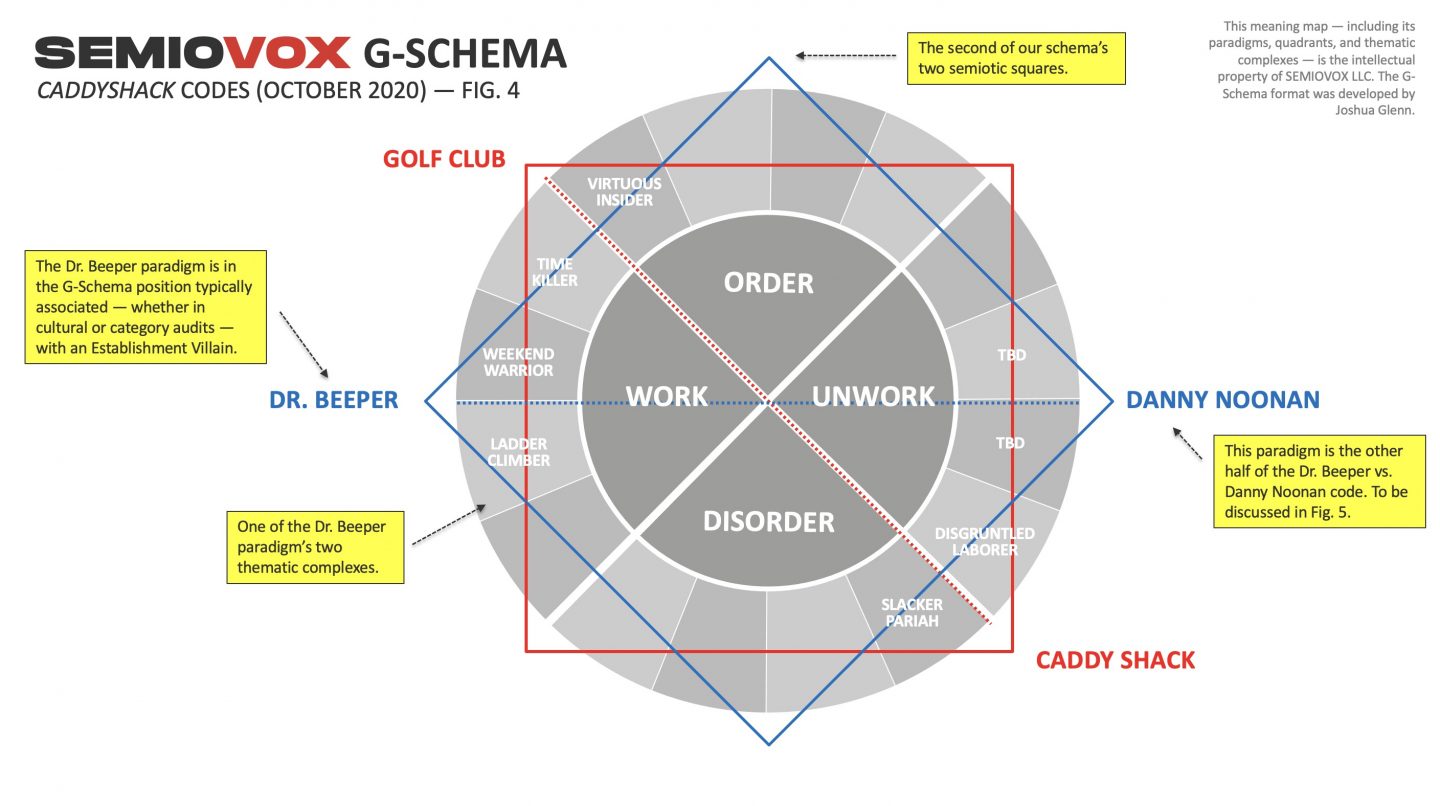

Voilà! Fig. 4 (above) features a second semiotic square, rotated 45 degrees from the first square. The resulting potent geometrical figure may be familiar to Muslims, for example, as a Rub el Hizb, to Hindus as a Star of Lakshmi, or to Mormons as the Seal of Melchizedek. Or to those of us who’ve made a pilgrimage to Norbiton, as the Plan of Sforzinda. However, I’m afraid there is no esoteric religious aspect to the G-Schema — sorry.

By identifying the four terms/paradigms whose relationship of contrasts and oppositions is mapped by this second square, and dimensionalizing each paradigm via an analysis of its two thematic complexes, we’ll eventually maneuver ourselves into a position where we can identify the first square’s “negative” (top-right vertex) and “neutral” (bottom-left vertex) terms/paradigms. One step at a time, though. In this post, we’ll analyze the Caddyshack semiosphere’s second code: Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan.

Paradigm

As Fig. 4 (above) indicates, the paradigm that I’ve named Dr. Beeper governs the Caddyshack meaning-map’s WORK quadrant. That is to say, the relatively minor character Dr. Beeper — played by the well-cast Dan Resin, who is perhaps best remembered as the Ty-D-Bol man — is the movie’s avatar of the repressive “work idea” that we discussed in this series’ second installment.

In my experience, the “positive” term of a cultural-production G-Schema’s second code is typically an Establishment Villain, of sorts. So Dr. Beeper — not Judge Smails! — is, according to my analysis, this movie’s villain. As with Grand Moff Tarkin in 1977’s Star Wars, for example, the Establishment Villain isn’t necessarily the most frightening, colorful, or evil baddie in the story; instead, he’s an avatar of what counts for authority and expertise within that particular semiosphere. When SEMIOVOX conducts a brand-communications audit of a product or service category, it’s fascinating to see what “villainous” paradigms emerge; in the Real Food space, for example, it’s the Old-Fashioned Farmer, while in the Oral Care space it’s the Dentist. These aren’t evil villains, of course; but in their respective semiospheres these paradigms represent reactionary authority figures.

Adapting and building upon the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Dr. Beeper categorical proposition like so: “It shall not be the case that there exists a Caddy Shack which is not Golf Club.” The proposition Golf Club simply takes it for granted that Caddy Shack shares its values, ideas, and so forth. It is left to the propositions flanking Golf Club (and therefore “infected” by uncertainty) on our diagram to do the dirty work of preserving this illusion. We’ll talk about Judge Smails in another installment; here we’ll look at how a Dr. Beeper figure deploys ideological methods, within a semiosphere, to prevent the dominant paradigm (here: Golf Club) of becoming aware of and subverted by the anti-anti-heroic paradigm represented, here, by Al Czervik.

As Caddyshack‘s villain, Dr. Beeper represents everything that Noonan feels pressured, by his family, to become. Judge Smails, who represents Order, and hails from an old-money aristocracy, does not represent an achievable goal for Noonan; but if he were to attend college and graduate school, he could be a Beeper — a doctor, lawyer, businessman, politician, etc., etc. In order to fully understand Noonan’s identity crisis, we’ll turn now to an investigation of the paradigm Dr Beeper’s two thematic complexes: Weekend Warrior and Ladder Climber. Along with the Time Killer theme analyzed in this series’ second installment, plus a fourth theme as yet unidentified, the source codes playing in these complexes will reveal the Caddyshack perspective on work and the work idea.

Weekend Warrior

Our first view of Dr. Beeper (15:58) reveals that he is what the TV Tropes wiki would describe as a Dr. Jerk — that is to say, an unempathetic, narcissistic medical professional. He is obsessed with golfing to the exclusion of his patients’ wellbeing, and we’ll soon learn that his dedication to his game has paid off: Beeper, it seems, has been the club’s golf champion for the past three years. The golf-obsessed doctor trope is an old one, of course; it’s mocked in the 1970 movie M*A*S*H, for example; and Golf Digest used to publish a ranking of the “Top 250 Golfer Doctors in America.” But the satirical portrait of Beeper is particularly harsh: “Just snake a tube down her nose,” he orders a flunky back at the hospital, “and I’ll be there in four or five hours.” Although bland and boring, he is the movie’s villain.

In Minima Moralia (w. 1944–1949, p. 1951), T.W. Adorno has a few harsh words to say about what passes for leisure activities in a modern capitalist society in general… and about the game of golf in particular. Even in the “desperate exertion” of bourgeois leisure activities, he laments in an entry titled “Timetable,” one does not experience true leisure, but instead merely a regimented “recuperation” — that is to say, a mere recharging of one’s robotic-worker batteries. Pointing to intellectuals as examples of those who derive deep pleasure from their work, and who therefore aren’t driven to seek substitute pleasures in hobbies and sports, Adorno suggests that we “could no more imagine Nietzsche in an office, the secretary answering the telephone in the foyer, sitting at a desk until five, than playing golf after a full day’s work.” We can certainly imagine Dr. Beeper and his peers doing so, though. Worse, we see that Beeper is addicted to his substitute pleasure, stealing time away from patients in distress in order to lower his handicap.

The creators of Caddyshack agree with Adorno: Being a weekend warrior is not something of which you should be proud. It’s embarrassing, really. And yet, within the Golf Club’s dominant discourse, we’re led to understand, Dr. Beeper’s companionship is to be assiduously cultivated — because he is so narrowly focused on winning at the game. His aggravated work ethic, which has apparently made him a successful doctor, cannot be turned off; even when he’s out on the golf course, that is to say, he’s working. I mean that figuratively, but as we’ll see when we examine the Ladder Climber thematic complex, below, it’s also true literally.

The weekend warrior, we’re led to understand, doesn’t — can’t — actually enjoy his leisure activities. Instead, they represent one more thing to be accomplished. Despite all the trophy-substitutes that they’ll amass in their lifetimes, like the shiny cars we see Czervik, Beeper, and Smails driving, these workaholics won’t ever win a life-trophy; but a golf trophy will fill that void, at least temporarily. Dr. Beeper’s no-nonsense attitude to his golf game is contrasted with Al Czervik’s (at 22:36), when Czervik, Wang, Drew Scott, Gatsby, and their caddies take a break from their own game to dance to Journey’s 1980 hit song “Any Way You Want It” — which blasts from Czervik’s golf-bag boombox. Speaking of Beeper’s car, when we see Spaulding puke through the Porsche’s sunroof, and Beeper (seen whisking his companion away, in horny anticipation) squish into the vomit (at 37:02), we realize just how Caddyshack‘s creators feel about such trophies.

Dr. Beeper isn’t the only weekend warrior at Bushwood, of course. The Bishop, who is willing to golf in a torrential storm if it means beating the club record, is another. Smails, too, takes his golf game far too seriously — but we’ll voyage inside Smails’s head in a later installment.

It’s instructive to note the thinly veiled antagonism between Dr. Beeper and Ty Webb — the “zen” golfer who doesn’t play against others, and doesn’t keep score. Shortly before Smails’s dustup with Czervik, Beeper says to Ty, “I thought you’d be the man to beat this year” — issuing a well-bred challenge, and insinuating that Ty’s reputation as a golf ace is doubtlessly unearned (1:09:46). “I guess you’ll just have to keep beating yourself,” quips Ty, who has no intention of signing up for the club tournament, with cool aplomb. Everything about the weekend warrior rankles Ty, though, as we learn a few moments later when Ty pretends to help break up the fight by putting Beeper, who actually was trying to break up the fight, in a headlock. Twice.

Although Beeper appears to be a better sport than Smails, he is no less obsessed with winning. When Czervik claims to have slightly injured himself during their money match, Beeper acts like a concerned doctor momentarily… only to note that the arm could be broken (an impossibility) and therefore Czervik will have to forfeit the match (1:26:08). He and Smails are shown gloating at several times during the match, when things aren’t going well for Czervik and Webb. But when he fails to sink his final putt, choking at the worst possible moment, Beeper gets his comeuppance, i.e., for having wasted the last three years of his life chasing golf glory (1:29:12). Note, too, that we almost never see Dr. Beeper hit a golf ball; presumably, this is because he plays with robotic efficiency — so who cares? Ty Webb’s eccentric game, Smails’s persnickety game, Czervik’s erratic game, even the Bishop’s divinely inspired game interest the viewer; Beeper’s game doesn’t.

So what does Danny Noonan make of Dr. Beeper? We’re never explicitly told — the two characters are rarely in the same shot. Still, when Noonan agrees to substitute for Czervik, it’s apparent to us that he’s not only extricating himself, George Bailey-style, from Smails’s Potter-esque web of favors and threats, but also rejecting Dr. Beeper as a role model. Also, Noonan is no weekend warrior. Unlike Adorno’s intellectual, he doesn’t love his work; he’s a savvy hustler, not a desk jockey. But unlike Dr. Beeper, et al., Noonan isn’t addicted to battery-recharging leisure pursuits, either. Except for an impromptu lesson from Ty Webb, we don’t see him golfing, at all, until he plays in the caddie tournament and then the money match. Yes, he’s decent at golf — but we see no evidence that he’s obsessed with the game. His idea of fun leisure activities involves smoking weed and getting laid… idle, truly enjoyable pursuits of which even Adorno might approve.

One final note about the Weekend Warrior thematic complex. As Fig. 4 indicates, it’s adjacent to the Time Killer thematic complex. These two complexes are similar in that they both bring to life and “problematize” the theme of conspicuous leisure. However, leisure is a continuum. So as we move closer to the ORDER quadrant — which is about old money and its privileges — the WORK-quadrant complexes become increasingly leisurely. The Weekend Warrior is a less leisurely complex, that is to say, than Time Killer (remember the day-drinking, Go Fish-playing characters we observed when discussing that complex); however, it’s a more leisurely complex than Ladder Climber — and also the fourth, as yet unidentified WORK complex.

Ladder Climber

I’ve tentatively named our other Dr. Beeper thematic complex “Ladder Climber” despite the fact that a career in medicine isn’t the same as one in business. That said, Dr. Beeper is depicted as being successful and powerful enough that he can blow off his duties and golf in the middle of the day; he has obviously succeeded in jumping through his profession’s various hoops.

What Dr. Beeper represents to Danny Noonan, a romantic dreamer uninterested in enduring the monotony and humiliations involved in climbing a corporate ladder, jumping through hoops, running a maze, etc., is the typical output of America’s success-factory: i.e., a robotic drone. The “New York intellectual” Irving Howe, who never earned a doctorate, once observed that the Ph.D. program is a relentless mill that grinds its victims down; only the least interesting thinkers typically survive such an ordeal. Dan Resin’s excellent delivery of the line, addressed to Lacey Underall, “Must be a nice change from dreary old Manhattan” (20:02), perfectly encapsulates Beeper’s obliviousness to his own utter tediousness… and makes it perfectly clear why Noonan might not want to end up like him. When not golfing, he bobs around the club aimlessly, at a loss for words. Note how unempathetic he is when the Bishop falls from grace (1:09:20).

Beeper’s beeper — a wireless telecommunications device allowing him to receive messages from the hospital when he’s at the club — is a metonymic device. It stands in for Beeper’s entire way of life, i.e., working all the time. (The character’s name, then, is a satirical aptronym; now that I think of it, so is Lacey Underall’s.) He’s testing his beeper when we first meet him (16:14), in a moment that one suspects is a reference to the self-important workaholic Dick Christie’s behavior in Play It Again, Sam (1972). Later, at the yacht club, after a dripping wet Beeper jokingly says, “Hey, man, save me a toke, ha ha ha!” to Spaulding, his beeper goes off. “Gotta do my ‘doctor’ thing,” he says, in a transparent effort to relate to the youth… before zapping himself — Woody Allen-style — with his own gizmo (53:50).

Although we’ve seen that his golf game is more important than his duties as a doctor, even on the golf course Dr. Beeper can’t stop checking his messages. This is how we know he’s a white-collar member of Bushwood, i.e., as opposed to old-money types like Smails and Webb, who barely seem to work at all. When his beeper beeps just before the match begins (1:20:25), Beeper wants to use Czervik’s golf-bag telephone to call in. Nervous about the money match’s ever-increasing stakes, Beeper tries to use his beeper’s urgent summons as an excuse to drop out of the game (1:25:04); when Smails tempts him with half of an $80,000 prize, Beeper mutters, “It’s probably just a routine emergency.” I think this gag — which suggests, again, how callous and arrogant he really is — is his last line in the movie.

What thematic complex might fall on the other side of Ladder Climber, in our G-Schema – i.e., the WORK aspect of the WORK/DISORDER paradigm located at our first semiotic square’s bottom-left vertex? We get our first inkling in the scene just before the game begins. Czervik is even more work-addicted than Beeper is; long before Gordon Gekko showed off his Motorola DynaTac 8000X in Wall Street (1987), we realize that Czervik doesn’t merely carry a beeper — he somehow has a rotary telephone built into his golf bag. Although Beeper is no fan of Czervik — who at 1:12:13 insultingly called him “Dr. Frankenpuff” — when we see the two men wrangling over whose need for the telephone is more urgent (1:20:40), we realize that they may have more in common than, say, Beeper and Smails do. When we get around to identifying the fourth WORK thematic complex, we’ll return to Czervik and his nonstop wheelings and dealings.

Danny Noonan wants to be carefree, and he seems to admire some of the trappings of wealth and status… but he doesn’t want to pay the price of success. His idol, at least for a while, is Ty Webb — who is entirely blasé about work and money. Dr. Beeper, who has succeeded in becoming a wealthy and well-respected medical professional, isn’t anyone’s idea of a good role model. As we saw when we examined the Weekend Warrior complex, he’s addicted to his leisure activity; and our analysis of the Ladder Climber complex suggests that he’s equally addicted to work. Night and day, he’s trapped on the hamster wheel. Noonan wants no part of this torment.

So there you have it: one-half of Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan, our Caddyshack meaning map’s second code. I’ve identified the paradigm Dr. Beeper’s contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. I’ve established not only what Dr. Beeper means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the character — but how Dr. Beeper means what he means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts to facial expressions, clothing, mannerisms, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what Dr. Beeper signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

The series’ next installment will take a close look at the paradigm Danny Noonan — this paradigm’s opposite number, i.e., the “rebel hero” term opposing the villainy of the paradigm represented by Dr. Beeper.

Click here for the Danny Noonan post.