Caddy Shack

This is the third installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

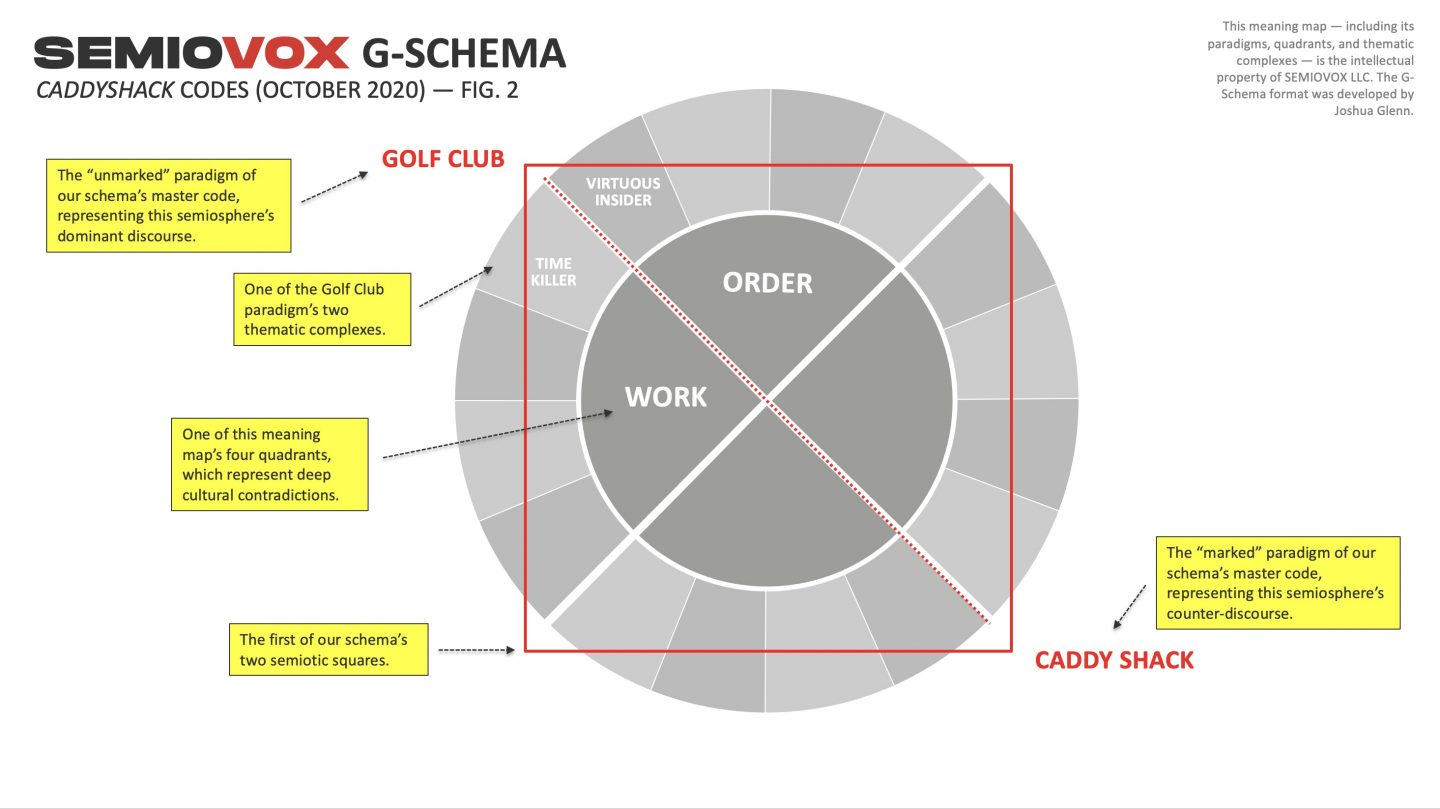

In this series’ previous installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed in order to map a product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s network of meaningfulness. Also, I demonstrated how I typically begin such a mapping exercise — i.e., by hypothesizing a “master code” and then, via a meta-analysis of the source codes (“signs”) surfaced via my analysis of an audit’s stimulus set, naming and bringing to life the two thematic complexes associated with each of the master code’s two paradigms. As Fig. 2 (below) indicates, our Caddyshack map’s master code is Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack. I’ve previously identified Golf Club’s thematic complexes as Virtuous Insider and Time Killer. In this post, we’ll take a close look at the paradigm Caddy Shack and its associated thematic complexes.

Paradigm

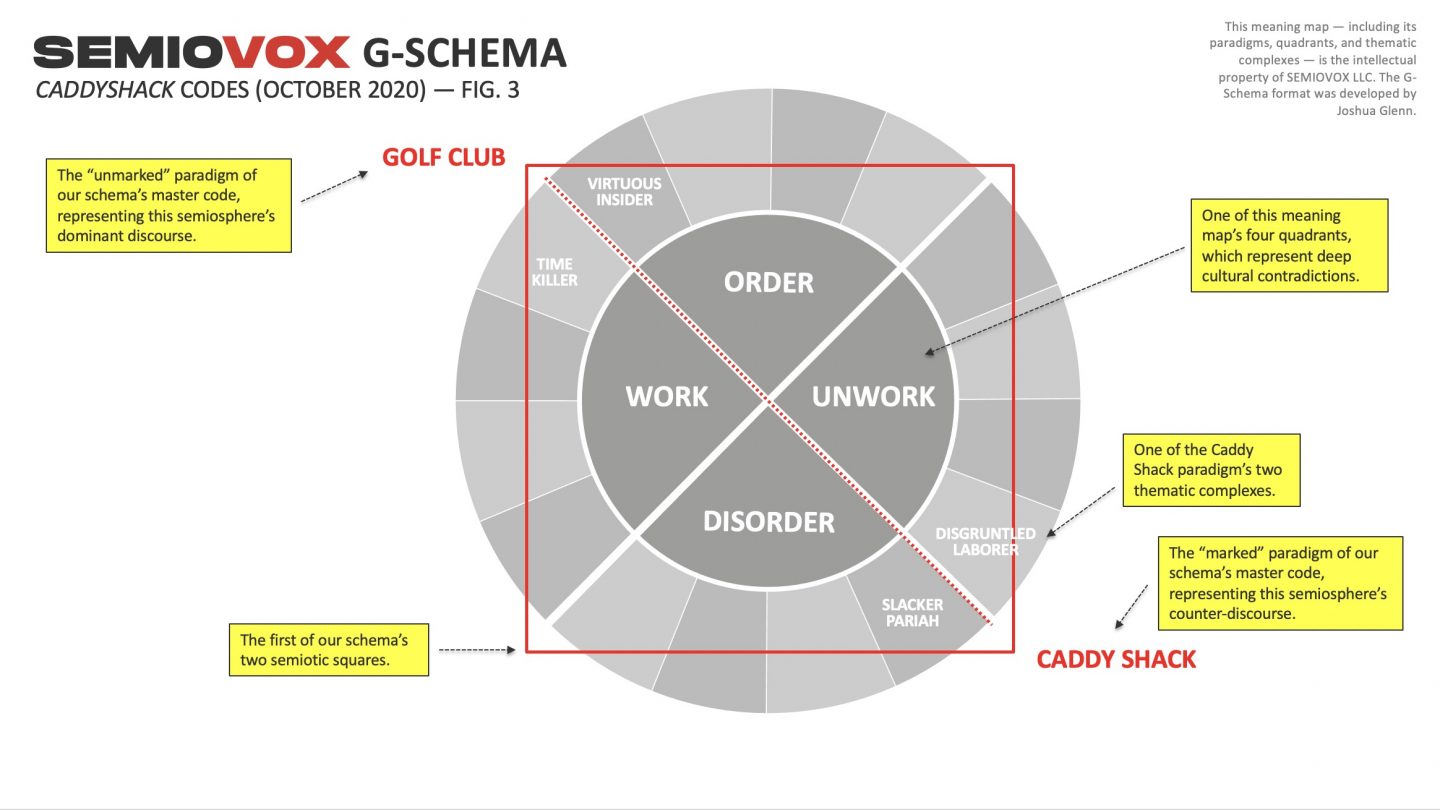

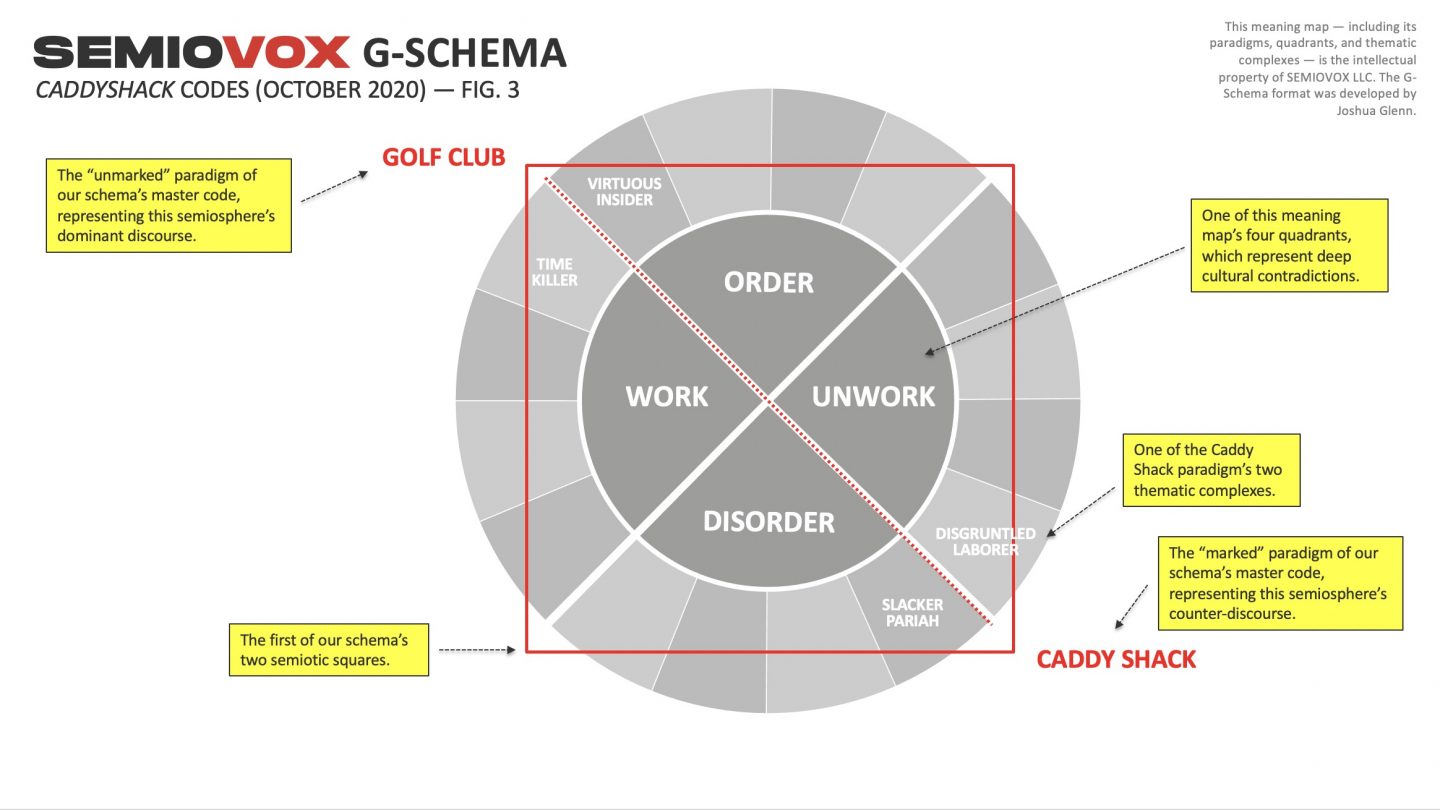

The paradigm that I’ve named Caddy Shack represents the Caddyshack semiosphere’s counter-discourse. Golf Club, as noted, is our dominant discourse; this paradigm, with its ideologies around Work and Order, reigns supreme. The paradigm Caddy Shack directly opposes Golf Club; it is the “disvalue” to Golf Club’s “value.” Caddy Shack’s two thematic complexes, as we will explore below, directly oppose Golf Club’s two thematic complexes. Whereas Golf Club straddles our map’s ORDER and WORK quadrants, the Caddy Shack paradigms straddles the quadrants DISORDER and UNWORK.

Adapting the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Caddy Shack categorical proposition like so: “There exists a Caddy Shack that is not Golf Club.” The Golf Club’s assumption or presumption that the Caddy Shack shares the Golf Club’s values, ideas, and so forth is not the case.

Semioticians talk about “unmarked” and “marked” terms within a semiosphere. The former are related to the semiosphere’s dominant discourse, an ideology rendered seemingly natural, inevitable, and permanent by its unremarkableness. Markedness, by contrast, is the state of standing out as nontypical or divergent. In this movie, the Bushwood country club and its members are orderly, well-groomed, tasteful, “normal”; the Caddyshack and its denizens are chaotic, sloppy and garish, weird. Judge Smails and his flunkies fight a never-ending war to keep Bushwood’s unmarkedness safe from the threat of marking. Nowhere is this made more clear than in the “poop in the pool” scene, the movie’s exact midpoint. But this tension is also manifest via wardrobe, language, accents, perspiration, etc.

My meta-analysis of the source codes surfaced and dimensionalized via an analysis of Caddyshack suggests that the paradigm Caddy Shack is constituted by the contrasting but not entirely contradictory thematic complexes Disgruntled Laborer and Slacker Pariah. The former plays in the quadrant UNWORK, the latter in the quadrant DISORDER.

Disgruntled Laborer

As Fig. 3 (above) indicates, the Disgruntled Laborer thematic complex is directly opposed to the Golf Club’s thematic complex Time Killer, wherein we discover a range of source codes communicating various notions about conspicuous leisure — i.e., the lazy, disobedient, ill-behaved actions of the leisure class, who consider Bushwood’s employees lazy, disobedient, and ill-behaved. There is evidence to support that opinion, which we’ll look at in the Slacker Pariah section of this post. The source codes that bring the Disgruntled Laborer thematic complex to life, however, portray Bushwood employees as hard-working, duty-bound, and reliable, if often disgruntled.

Our first view of Danny Noonan (2:02), for example, shows him up and at ’em before anyone else in the family. He barely has time to eat breakfast, and leaves home even before his blue-collar father, who works at a lumber yard, does. He’s saving his caddying tips, rather reluctantly, for college. (The best tipper, he suggests, in a moment of foreshadowing [2:49], is Ty Webb.)

When Noonan rolls his bicycle onto the grounds of Bushwood, as he passes by two club members on horseback, he tugs on his cap’s brim deferentially (4:28). It’s a neo-medieval moment: a peon truckling to mounted nobles. Pulling down the front of one’s cap (or tugging at one’s forelock) is, of course, a traditional demonstration of an inferior’s respect to superiors.

Noonan’s fellow caddy and rival Tony D’Annunzio (Scott Colomby) boasts many flaws, but he’s certainly not lazy. At 11:45 – 12:45, we see him struggling along in the wake of the doddering golfers Mr. and Mrs. Havercamp. We also spot D’Annunzio picking up shifts as a bartender at various stations within the Bushwood complex; and Noonan works there as a waiter. Other club employees, including the groundskeeper Sandy McFiddish, caddy wrangler Lou Loomis, Smoke Porterhouse (portrayed by Hammond electric organ maestro Jackie Davis), and Charlie the Cook, may skive off at times — when we first see Lou, he’s on the phone with his bookie — but the general impression is that they run a fairly tight ship.

The employees are disgruntled, though. When word gets out about the money match between Smails and Beeper and Czervik and Webb, they drop everything in order to root for Czervik and Webb, or more precisely, against Smails and Beeper… not to mention place innumerable bets on the match, too. (When Lou, who acts as referee of the money match, ignores the explosions and chaos at the movie’s end in order to render final judgment, one wonders whether he’s doing so entirely for altruistic reasons.) And who can forget Porterhouse’s destructive act of revenge (17:35) when he overhears Smails and the Bishop laughing at a joke about “the Jew, the Catholic, and the colored boy who went to Heaven?” Not me, anyway.

Maggie O’Hooligan — the Irish exchange student played by Sarah Holcomb, who made her debut appearance as supermarket cashier and good-time gal Clorette DePasto, in Animal House — is perhaps the hardest laborer of all. In fact, except for when she’s mostly naked we rarely see her out of uniform. An immigrant, albeit a temporary one, Maggie’s work ethic puts Noonan’s and D’Annunzio’s to shame; she has internalized the “work idea” promulgated by the Golf Club. The tragedy of this character, Caddyshack would have us understand, is that she has also internalized her culture’s prohibition on abortion. The one somber scene in the movie (beginning at 1:05:00) depicts Noonan’s awkward efforts to comfort Maggie when she believes that she’s become pregnant. And the nighttime scene (beginning at 1:11:06), in which Maggie skips around the 18th hole her nightgown, feels like an outtake from Friday the 13th — which debuted the same year.

This is a sweaty thematic complex. The caddies huff and puff, and perspire freely. As noted in the previous series installment, this sort of thing is frowned upon by the Bushwood elite. (When Mr. Havercamp says “Oh golly, I’m hot today,” it’s an ironic moment; he’s referring to his lousy golf game, but his caddie, D’Annunzio, is slick with perspiration.) PS: As we’ll see, his sweatiness is a not insignificant aspect part of Al Czervik’s anti-appeal.

The Disgruntled Laborer thematic complex is governed by our map’s UNWORK quadrant — which is not to suggest the laborers don’t work. The map’s WORK quadrant is about an ideology of work — the Protestant Work Ethic, the idea that one can feel satisfied that one has earned one’s privileged status, even if one has inherited one’s wealth and social position. The UNWORK quadrant, by contrast, features thematic complexes that in various ways challenge the WORK quadrant’s smug, blinkered dogmatisms.

One final note: I’ve described the club’s employees as “laborers” rather than “workers” in order to distinguish, with Hannah Arendt, between the homo faber who embodies the values of permanence and duration, and the animal laborans, whose values are those of productivity and sheer survival. Per Arendt, labor is a cyclical, repeated process that carries with it a sense of futility; Caddyshack suggests that the caddies’ labor is not fit for humans. Why not call this quadrant LABOR? Because, as we’ll see when we explore the other thematic complexes here, other work-opposed themes are in play.

Let’s turn now to the paradigm Caddy Shack’s other, contrasting yet complementary thematic complex.

Slacker Pariah

Whereas the paradigm Caddy Shack’s Disgruntled Laborer thematic complex falls into our meaning map’s UNWORK quadrant, the Slacker Pariah thematic complex falls into our DISORDER quadrant. Here, we find that the caddies and other Bushwood employees subvert the Golf Club’s discourse not merely through their sweaty disgruntlement but via their foot-dragging, rowdy, disobedient, altogether carnivalesque behavior.

Note that this theme is what Caddyshack was originally supposed to be about — that is to say, the anarchic antics of Animal House as performed by working-class grunts instead of preppies. Although the movie evolved into much more than that, the remnants of this original idea, inspired by Brian Doyle-Murray’s and his brother Bill Murray’s anecdotes about caddying in suburban Chicago as teens, can be glimpsed in this complex’s source codes.

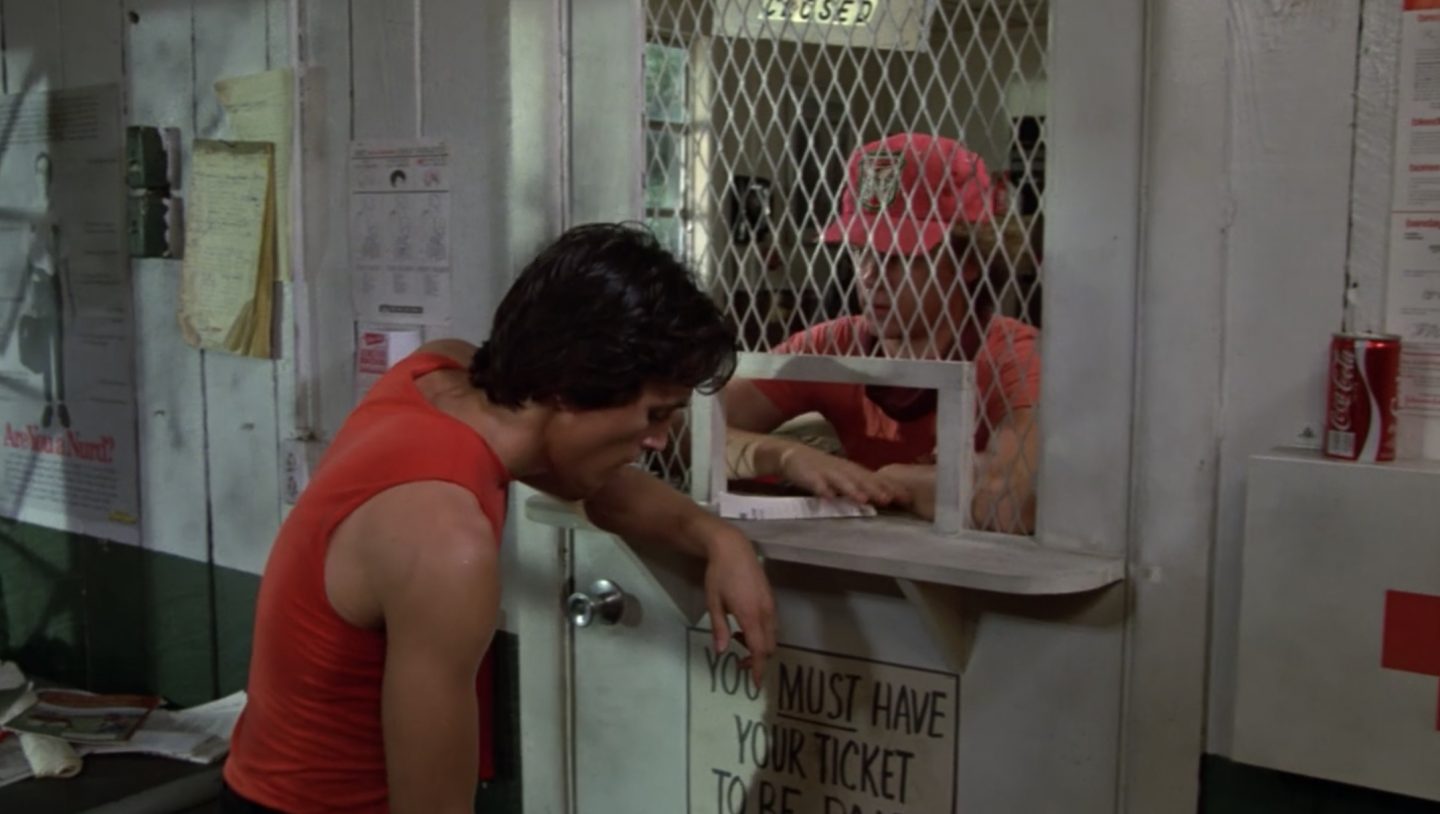

When the caddies aren’t hard at work, they’re goofing off. They aren’t idlers, but slackers; that is to say, their disorderly unworking doesn’t transcend and reject the Golf Club’s work ideology. [1] Instead, they find small ways to cheat the system, to get away with breaking the rules, to survive their ordeal. In our first view of the actual caddy shack, everyone is horsing around — to the tune of Eddie Cochran’s 1958 slacker anthem “Summertime Blues” (“Well I’m a gonna raise a fuss, I’m gonna raise a holler / About workin’ all summer just to try an’ earn a dollar”). Even Lou, the erstwhile enforcer of discipline among the caddies, is placing a bet on the Mets when first seen. The smug assumption of virtue that provides moral support to the Golf Club’s dominant discourse isn’t anywhere to be found here. Although the caddies do work hard, as we’ve seen, they don’t pat themselves on the back about it. They just want to get paid, and goof off.

We don’t actually see the caddies goofing off as often as one might expect; no doubt most of this material ended up on the cutting room floor. Still, we know that it often happens. After breaking up the fight between Noonan and D’Annunzio (13:30), a fed-up Lou chastises the caddies for “fooling around on the course, bad language, smoking grass, poor caddying” (14:40). (Part of the threat posed by Czervik is his whole-hearted embrace of this sort of behavior. At 25:50, for example, we see a group of caddies eating sandwiches and watching a western on his high-tech golf bag’s TV set.) At 42:30, Noonan and Maggie sneak off for a nooner, spied on by D’Annunzio. And from 1:23:00 through the end of the movie, an ever-growing group of caddies and club employees surreptitiously shadows the Smails-Czervik money match across the entire golf course, only coming out into the open for the game’s final moments. There’s a live-action Disney quality to most of these caddy scenes; that is, we get the impression of innocent shenanigans.

But the caddies aren’t merely slackers, in the movie’s schema; they’re also pariahs. They’re the perpetual danger, to refererence Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection, which threatens the dominant discourse (i.e., in this case, the Golf Club). “Discourse,” Kristeva explains in her Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, which also came out in 1980, “will seem tenable only if it ceaselessly confronts that otherness, a burden both repellent and repelled… the abject.” The Golf Club’s order constitutes itself, according to this theory, only by repressing and excluding the disorder represented by the club’s caddies. But per Kristeva, the abject is no respecter of borders or rules; it draws attention to the fragility of “the law” by disturbing identity, system, order. It breaks down boundaries, disobeys orders, defiles privileged spaces.

No doubt the most memorable caddy-goofing scene in the movie is the invasion of the club’s pool at 43:10 — culminating in the “poop” incident, which transpires at just about exactly halfway through the movie. As a Kenny Loggins song plays, the caddies make the most of their allotted 15 minutes of leisure — jumping in the pool fully clothed, exposing themselves indecently, ignoring the lifeguard (and toppling him into the pool), etc., etc. We’ll discuss the various violations of Bushwood order, here, elsewhere in the series. But suffice it to say that this is a carnivalesque scene. We see D’Annunzio stop up Spaulding Smails’s snorkel; his sister Joey, meanwhile, tears off her caddy’s ballcap to unleash a glorious mane of frizzy hair — a gender-reveal moment, of sorts, as well as a rebuke to the club’s carefully coiffed WASP women — and shouts, “You shave your ass!” at the lifeguard before diving into the pool (43:59). D’Annunzio lasciviously, expertly rubs suntan oil onto Spaulding’s niece, Lacey. And then there’s the “doodie” — a misplaced candy bar, bumped into by Spaulding (48:00). It’s all very abject, indeed.

One final note on the thematic complex Slacker Pariah. The worst insult that one caddy can use in reference to another, we discover, is “brown-noser.” (An exceedingly abject slang term.) D’Annunzio, Motormouth, and Noonan’s other peers ritualistically intone this jibe (18:50) when Noonan volunteers to caddy for Judge Smails — an assignment usually to be avoided — because he hopes to win a college scholarship the disposition of which Smails control. Again at 1:19:45, when Noonan is selected to be Smails’s caddy for the money match, D’Annunzio and Motormouth mutter, “brown-noser.” In this vulgar idiom we find a message about both slacker-dom and pariah-dom. The slacker hates a brown-noser, because the brown-noser rebels against the slacker’s rebelliousness, seeking to ingratiate himself with the boss; and the pariah hates a brown-noser, because the brown-noser rejects the pariah’s rejection, seeking to worm his way into the Establishment. Within the Caddyshack semiosphere, preppies — like the law student Chuck — are taught to brown-nose; but proles loathe it.

It’s a poignant moment, then when (at 1:31:52) the caddies, including D’Annunzio, cheer Noonan on — once Noonan betrays Smails, that is.

So there you have it, the other half of Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack, our Caddyshack meaning map’s master code. In this post, I’ve identified the paradigm Caddy Shack’s two contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. I’ve thereby established not only what the caddy shack means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the caddies’ subculture — but how the paradigm Caddy Shack means what it means. In doing so, I’ve surfaced many of the key visual and verbal cues, from speech acts and tonality to hairstyles, clothing, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what the paradigm Caddy Shack signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of a counter-discourse to, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

This series’ next installment will look at one-half (that is, one of two paradigms) of the second Caddyshack code: Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan.

Click here for the Dr. Beeper post.