Al Czervik

This is the ninth and final installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

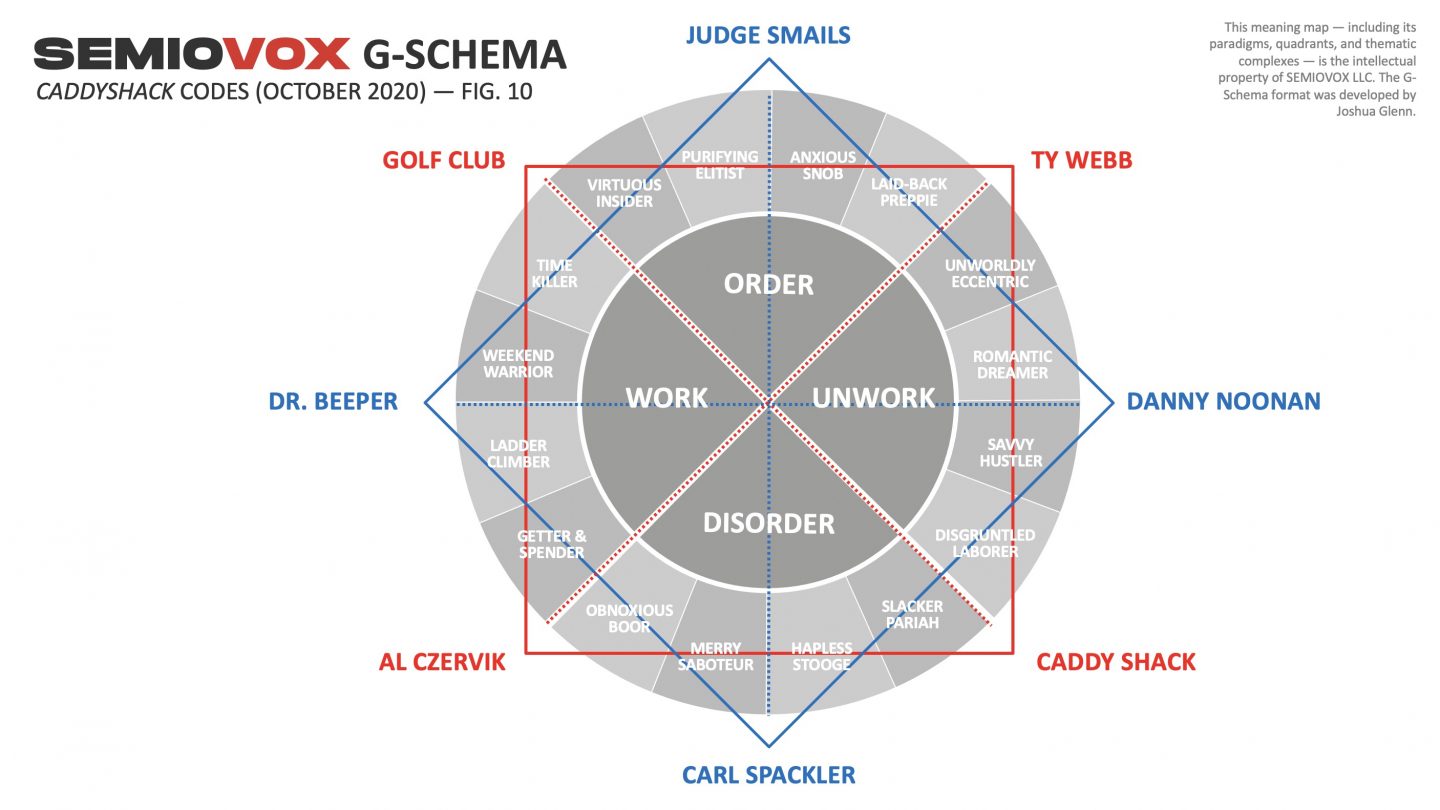

In this series’ second installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed (over the past 20+ years) in order to productively and insightfully map any product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s “semiosphere” — which is to say its network of meaningfulness, a matrix of values and disvalues that subtly helps shape and guide perceptions and sense-making within this space.

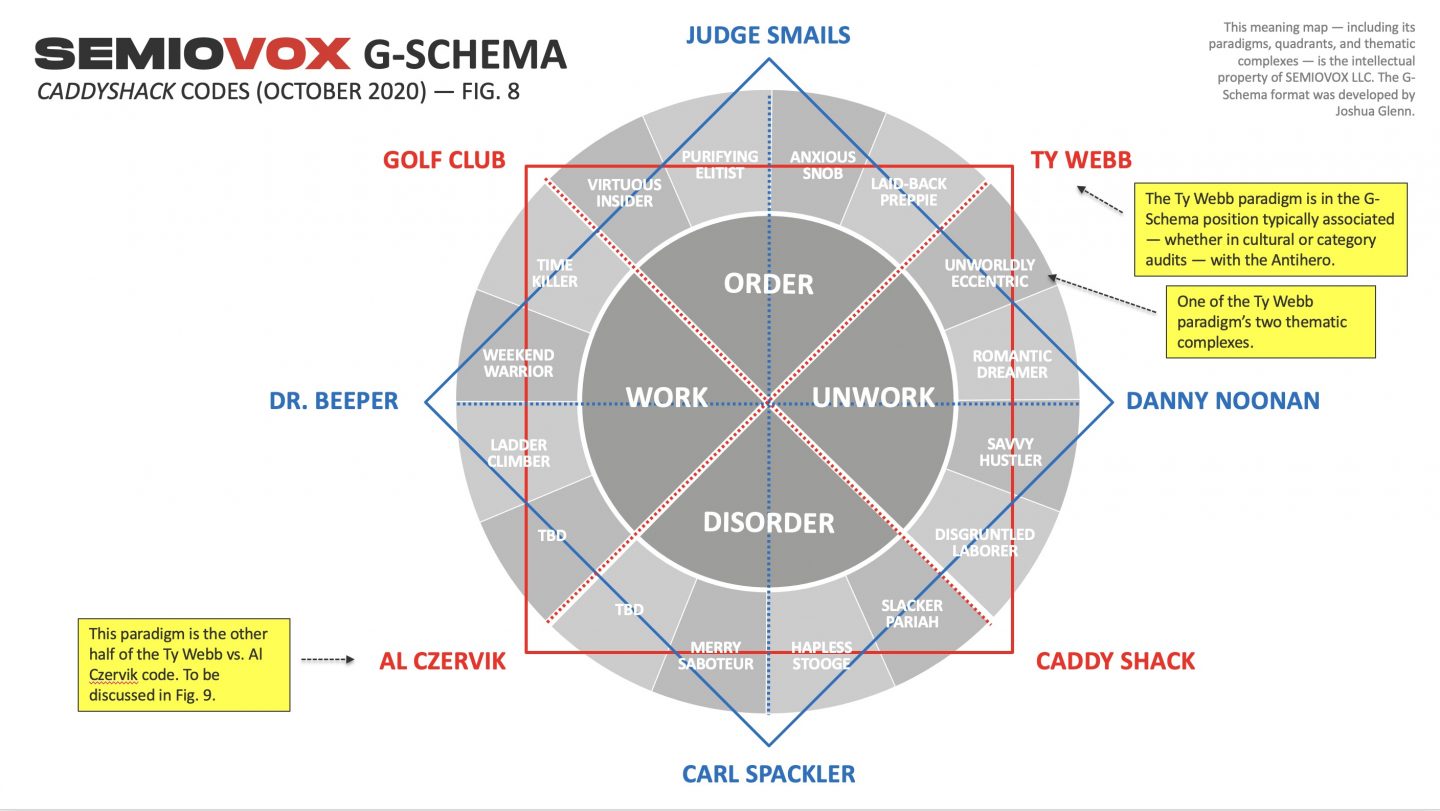

By the end of this series’ eighth installment, we had arrived at the semiosphere-mapping stage illustrated in Fig. 8 (below). Our meaning-map’s “master code,” Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack, has been thoroughly explicated, and its thematic complexes brought to life via source codes (“signs”) surfaced and dimensionalized through my analysis of the movie; the same goes for this semiosphere’s second code, Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan, as well as its third, Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler. Finally, we’ve explicated the paradigm Ty Webb, i.e., the first half of our fourth and final code, Ty Webb vs. Al Czervik. At long last, we’re ready to wrap up our Caddyshack analysis.

As discussed in the previous installment, Ty Webb vs. Al Czervik is the Caddyshack semiosphere’s hermeneutic code. The paradigms Ty Webb and Al Czervik, that is, challenge and subvert the structure of meaningfulness established by the master code Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack. The paradigm Ty Webb does so in an antiheroic fashion — by rejecting both the “value” Golf Club and the “disvalue” Caddy Shack; the character Ty Webb refuses to buy into either the dominant culture or the counterculture. The antihero wants it all; they want to have their cake, and eat it too; faced with an either/or decision, they choose “all of the above.” Al Czervik, as we’ll demonstrate in this installment, also refuses to buy into either the dominant culture or the counterculture… but this paradigm is anto-antiheroic. The anti-antihero doesn’t want anything this semiosphere has to offer; faced with an either/or decision, they choose “none of the above.”

An anti-antihero is always a troubling, fascinating figure because they find themselves trapped in a semiosphere that they want out of. The anti-antihero serves to remind us that a semiosphere’s taken-for-granted assumptions, which seem natural, permanent, and inevitable, are in fact unnatural, impermanent and evitable. Our experience is framed by convention; the anti-antihero force us to recognize the framing. They’re villainous figures, of sorts — yet we can’t help but admire them. Another way to describe the anti-antihero, then, is: the sympathetic villain. A villain whose motivation is orthogonal to his or her semiosphere’s master code.

If, as I’ve suggested in previous posts, the top-left vertex of a G-Schema (in this case, the paradigm Golf Club) can be thought of as the semiosphere’s superego, the top-middle vertex (in this case, Judge Smails) as its ego, and the top-right vertex (Ty Webb) as its id, then the bottom-left vertex can be thought of as that aspect of the unconscious which views the whole psychic apparatus with detached, compassionate, philosophical irony. Whereas the antihero is cynical, the anti-antihero laughs at the absurdity of everything.

Chris Nashawaty’s book Caddyshack: The Making of a Hollywood Cinderella Story informs us that Harold Ramis, originally wanted Don Rickles for the part of Al Czervik. But by the summer of 1979, Rodney Dangerfield was in the middle of an incredible 36 guest-appearances run on The Tonight Show, reducing Johnny Carson to tears almost every time. The character didn’t have a lot of lines in the first draft of the script. However, after the producers saw the first rushes of Dangerfield’s scenes, they told Ramis that he needed to give the Czervik character a larger role.

To quote a character in Samuel Beckett’s Watt:

“The mirthless laugh is the dianoetic [philosophical] laugh, down the snout—Haw!—so. It is the laugh of laughs, the risus purus, the laugh laughing at the laugh, the beholding, the saluting of the highest joke, in a word the laugh that laughs—silence please—at that which is unhappy.”

Dangerfield’s laugh is precisely this: mirthless, down the snout, a “Haw!” He is extraordinary in this, his first movie role. He was perfectly cast for the part, since his mirthless comedy is about the absurdity of… everything.

Paradigm

We’ve used Julia Kristeva’s theorizing to help us elucidate paradigms elsewhere in this series. When it comes to a semiosphere’s anti-antihero paradigm, it might be helpful to turn to her writing on the “semiotic chora.” She borrows the term chora from Plato’s Timaeus to denote an essentially mobile (uncertain, indeterminate) “articulation” that precedes and disrupts a “disposition… that gives rise to a geometry.” Kristeva helps us understand that the paradigms Golf Club, Caddy Shack, Judge Smails, Carl Spackler, Danny Noonan, and Dr. Beeper (in our analysis of Caddyshack) are certain, determinate dispositions that together give structure to this semiosphere. Even Ty Webb, our antihero, troubles the paradigm only to the extent that this paradigm won’t be governed by either extreme of the master code. In rejecting both extremes of the master code, however, the paradigm Al Czervik makes us fatally aware of this semiosphere’s inherent limitations.

The chora, according to Plato, is (in Kristeva’s words) “a mobile receptacle of mixing, of contradiction and movement, vital to nature’s functioning.” If the semiosphere represents the seemingly inevitable construct that is culture, then the chora reminds us that culture is preceded by nature. If in culture only some things are possible, in nature all things are possible. So in any semiosphere, the chora is that which opens our eyes to the artificiality of that which seems but is not nature; it is a “dancing body” (from the Greek khoreia, “dance”) in perpetual motion, suggesting infinite possibility. An anti-antiheroic character like Al Czervik dances through a semiosphere in an open, mobile, non-subjugated manner, crashing the party… and encouraging the partygoers to consider that another world is possible.

Adapting the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Al Czervik categorical proposition like so: “There exists a Golf Club which is Caddy Shack.” This proposition suggests just how radically deconstructive and threatening an Al Czervik-like figure is within a semiosphere — they deny the validity of the fundamental “tentpole” opposition structuring the system of meaning! Czervik is a Samson figure, threatening to push over the temple’s pillars and bring the roof crashing down on everyone inside — destroying not only Golf Club, in this example, but Caddy Shack. As I’ve suggested above, the anti-anti-hero’s motivation is this: He has stumbled into the wrong narrative, and he wants out. Which serves to alert those of us within the narrative that… it’s just one of many possible narratives.

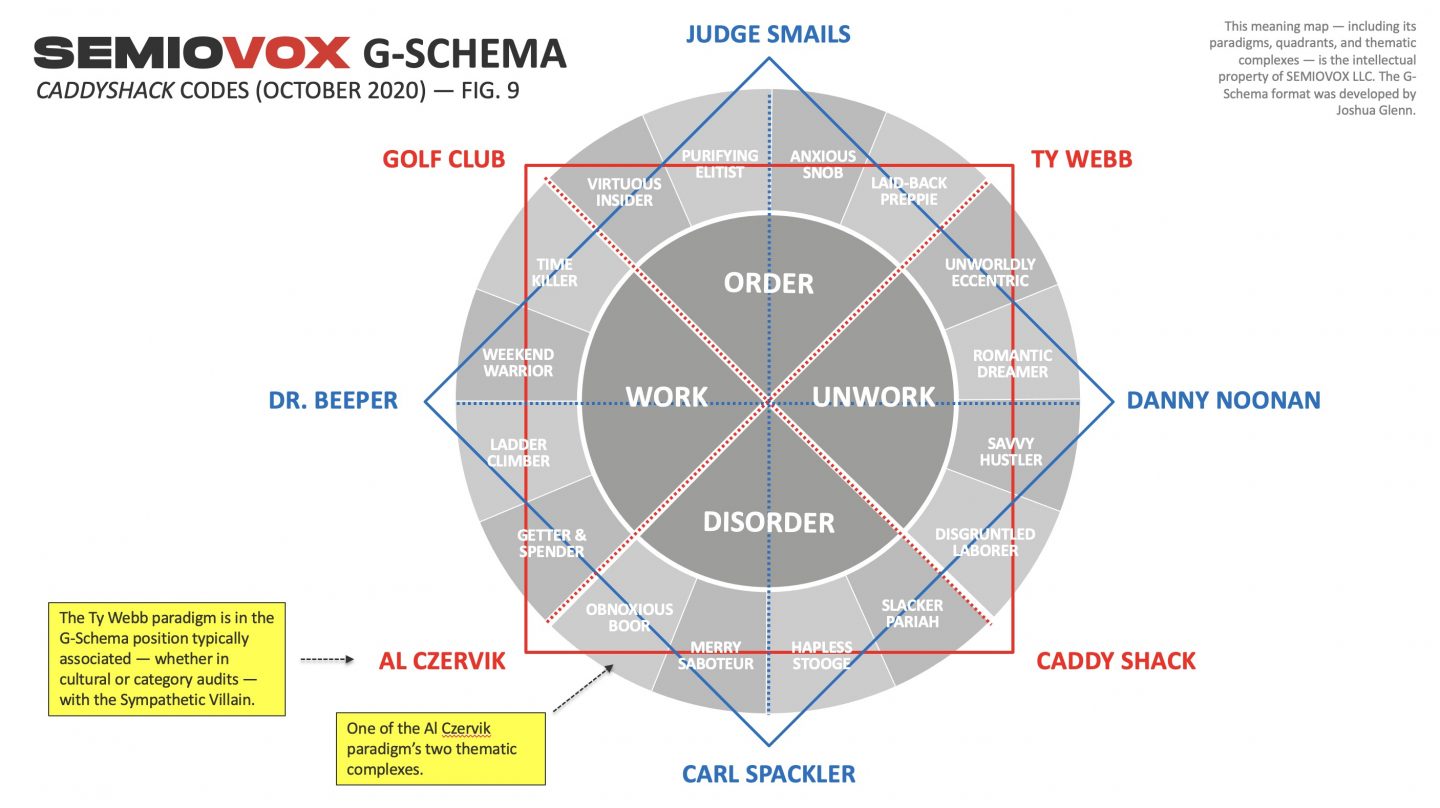

As Fig. 9 (above) indicates, my analysis of Caddyshack — and an abductive meta-analysis of the map itself, triangulating our way (as this series has demonstrated) toward the elusive bottom-right vertex — suggests that the paradigm Al Czervik is brought to life by source codes (“signs”) playing in these two thematic complexes: Obnoxious Boor and Getter & Spender.

Obnoxious Boor

In Czervik’s first appearance (17:45), he and his associate, Mr. Wang (played by Dr. Tsung-I Dow, a history professor at Florida Atlantic U.), roll up to Bushwood in a scarlet ’64 Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III convertible. The car’s horn tootles “We’re in the Money.” Czervik, who sports red pants, a green shirt, and a rainbow-striped cardigan, is obviously a cretin, a boor, a goon.

Czervik is a guest of the Scotts — one of Bushwood’s hard-partying couples of whom Judge Smails disapproves. (Drew Scott is played by Brian McConnachie, who,as noted elsewhere in this series was one of the main writers for National Lampoon and then Saturday Night Live.) At 20:18, we find Scott and his crony Gatsby (Scott Powell, a founding member of Sha Na Na, and an orthopedic surgeon in real life) snickering as Czervik loudly castigates and harasses Judge Smails; they appear to be day-drinking.

Things rapidly devolve from bad to worse, for Bushwood’s sedate, rather zombified members, as Czervik and his group disrupt the serenity of the country club. At 22:25, Czervik starts blasting music and dancing enthusiastically, if rather spasmodically. Wang, Scott, Gatsby, and their caddies follow suit. He offers beers from his portable keg. At 26:48, he attempt to bet Smails a thousand dollars that he’ll miss his putt. At the 4th of July gala dinner, Czervik disrupts Smails’s dinner (30:30–31:30) by bragging about his wealth (“If you keep busting your hump 16-20 hours a day,” he ventriloquizes his doctor, “you’ll end up with a 60 million funeral”), insulting Bushwood’s food (“This steak still has marks where the jockey was hittin’ it”), and loudly farting.

While the conversation at Smails’s table is dull and formulaic, we see Scott, Gatsby, another guest — this is Douglas Kenney, National Lampoon cofounder and coauthor of the movie — and their dates yukking it up. Czervik’s subversive attitude towards Bushwood, his lack of fucks to give, is contagious. As Fig. 9 shows, the Obnoxious Boor thematic complex is adjacent to the Merry Saboteur complex. Although Czervik doesn’t go around lopping the heads off of flowers, much less dynamiting the golf course, make no mistake: He poses an existential threat to Bushwood.

Getting up from the dinner table, Czervik proceeds through the dining room like an insult comic — dropping truth bombs right and left. Bushwood is antiquated, stuffy, tedious, pretentious, and preposterous, he wants everyone to know. When an older gentleman expresses displeasure with Czervik’s antics, he replies, “The graveyard is two blocks to the left” (31:09). A few moments later, as he approaches the dance floor, Czervik scoffs, “The dance of the living dead!” In one of his best lines of all, at 36:05 he confides to his associates that “I never saw dead people smoke before!”

Czervik is particularly savage towards Smails. Their confrontation in the club’s Pro Shop we’ve already discussed, in this series’ Judge Smails installment. Catching sight of the judge in his formal red jacket, at the 4th of July gala, Czervik pretends to think he’s a waiter… and even offers him a tip. Then he calls Smails “Captain Hook” — a double jibe, mocking the naval-ish jacket and Smails’s epic slice, earlier. (Smails’s niece, Lacey, enjoys the spectacle, laughing openly at her uncle.) He pretends to flirt with Mrs. Smails: “You must have been something before electricity.” As for their grandson, Spaulding, Czervik rolls his eyes and says, “Now I know why tigers eat their young.” It’s a shock-and-awe campaign of insult comedy.

Although Smails perceives him as a déclassé striver hoping to win acceptance to an elitist sanctuary, again and again Czervik makes it clear that the Bushwood scene is not for him. Flinging cash at the club’s band, he importunes them to play disco music. Not satisfied with this disruption — which Smails and his wife actually seem to enjoy, somewhat — he cuts in on their dance, and makes obscene remarks to Mrs. Smails. “You’re a lot of woman, you know that? Yeah, wanna make 14 dollars the hard way?” He’s not there to make friends. In a world characterized by jockeying for social status, his lack of interest in doing so makes him a uniquely liberated man.

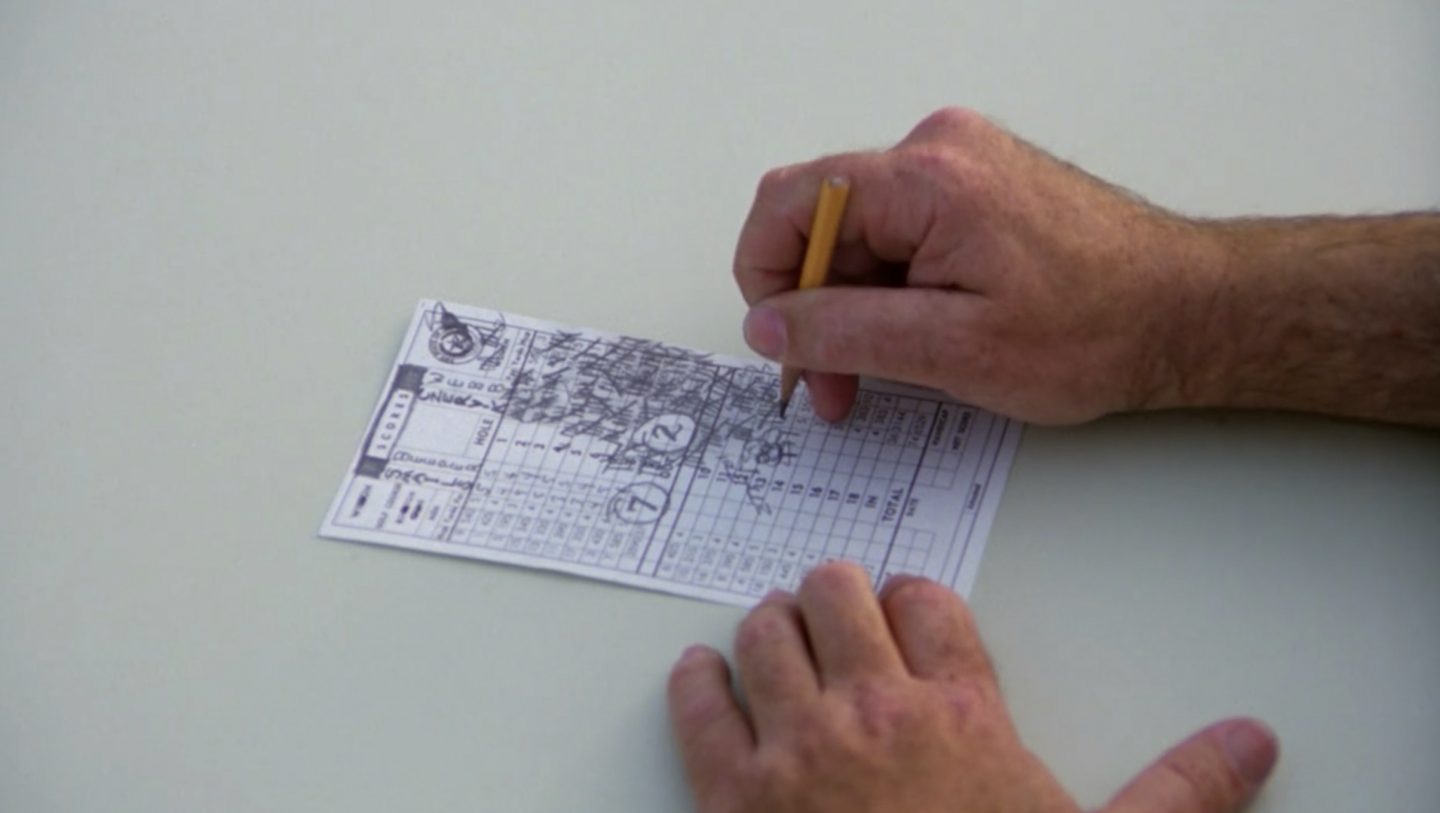

Even Czervik’s lousy golf game is a sign of his liberation. As noted elsewhere in this series, prowess at golf is regarded — within Bushwood’s preppie culture — as evidence that one truly deserves one’s (inherited) privilege. Czervik is terrible at golf. If Smails’s game is too fussy, too inhibited, Czervik’s is eccentric, rushed, and entirely ineffectual. At 1:25:14, and throughout the money match, we see him struggle with every stroke.

It’s not that Czervik is unaware that Smails, et al., are obsessed with status. At the yacht club, he goes — literally — out of his way to demonstrate to Smails that he is by far the wealthier man. “Hey Smails! My dinghy’s bigger than your whole boat!” he trumpets, at 56:48. He’s a Trump-esque parvenu obsessed with penis size… an unpleasant figure, to be sure. And yet, because his target is Bushwood and Smails, because he’s an amusing populist who takes down elitists with brio, we find him oddly charismatic. His final line in the movie, “Hey, everybody! We’re all gonna get laid!” (1:34:20) might as well have been Trump’s 2016 campaign platform.

As Fig. 9 indicates, the Obnoxious Boor thematic complex is opposite the Laid-Back Preppie complex. Czervik is neither preppie nor laid-back. At 25:40, we find him posing in front of a sign for his own condo development; his sweaty shirt indicates that unlike Ty Webb, Al Czervik runs hot, not cool. Although both characters refuse to make the either/or choice — Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack — demanded by this semiosphere’s master code, the antiheroic Ty Webb is no outsider. He wants to be in the club but not of the club. But Czervik stands outside the movie altogether; he’s an alien invader!

Getter & Spender

What, exactly, is Czervik doing at Bushwood? What does he want? When it comes to a semiosphere’s anti-antihero, the question of motivation is always a tricky one. The anti-antihero’s motivation is orthogonal to the semiosphere’s master code. Although Czervik is a builder, he’s very much in the business of the dissolution of structure. He doesn’t want to join the club, nor does he want to join the caddies in their countercultural resistance to the club. Like Galactus, devourer of worlds, he’s come to destroy.

We get a foreshadowing of Czervik’s sinister intent — but possibly salutary, too; it depends on whether or not you want Bushwood to survive — at 8:27, when club’s groundskeeper explains to Smails that the gopher has been driven onto the course by the abutting new condo development. Cut to the source of this disruption, with the sign Czervik Construction Co. visible. However, for a while at least, we’re just shown examples of Czervik’s extravagant wealth — we don’t know exactly what he may be scheming.

Note that on our map, the Getter & Spender thematic complex is adjacent to the Ladder Climber complex. Like Dr. Beeper and Bushwood’s white-collar, nouveau riche members, Czervik is concerned primarily with getting ahead. Unlike these doctors and lawyers, however, he is an entrepreneur. He’s not climbing any ladders, he’s making his own way in the world. As a result, he’s become wealthier than anyone at Bushwood.

At 21:20, we get our first of several glimpses of Czervik’s golf bag in action — a high-tech version of Felix the Cat’s magic bag of tricks. It fires his clubs into the air via remote control, dispenses beer, plays music and TV. Czervik’s putter, with its computerized sighting mechanism that transforms golf into a video game is a gift, he claims, perhaps facetiously, from Albert Einstein. “Nice man. Made a fortune in physics” (24:41). And of course, Czervik’s endless over-tipping — the caddies, the bartender, the band, the referee of the money match — is another sign of his seemingly vast wealth.

However, at 25:37, while the caddies watch a western on his TV set, Czervik admires his condo development… and reveals his motivation. “Hey, I’d bet they’d love a new shopping mall right here,” he muses aloud. “I tell ya, country clubs and cemeteries are the biggest wastes of prime real estate.” How do we feel about Czervik now? We may applaud his efforts to mock and dismantle an oppressive, elitist institution like Bushwood… but if his disruptive innovation involves paving paradise to put up a parking lot (“PARKING GALORE,” boasts his billboard), should we still applaud? This is what it means, structurally, to be an anti-antihero. Czervik is a villainous figure… yet not an unsympathetic one. We admire him for subverting the semiosphere’s master code… yet what if something worse replaces it?

The billboard scene helps us understand Czervik’s utter liberation from Bushwood’s conventions and culture. He’s there to scope the place out before deciding whether he’ll raze it to the ground. His joking about graveyards and the living dead, at the 4th of July gala, chime with his revealing remark about cemeteries here. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living, this capitalist revolutionary understands. In order to make one’s fortune, it’s necessary to be liberal, not conservative; tradition just gets in the way.

Contrasting the Getter & Spender thematic complex with the Unworldy Eccentric complex — its opposite number, per our meaning map — we can see that whereas the antiheroic Ty Webb romanticizes his do-nothing way of life, seeing it as a kind of spiritual discipline, the anti-antiheroic Czervik is ultra-pragmatic about making his fortune. The hustle, for him, is real. No one is more perplexed by Ty Webb than Al Czervik, as we find in the scene at 1:12:25, when Czervik struggles to understand why Webb won’t play golf for money. Everything is about competition and winning, for Czervik; this aspect of his character — the compulsive betting, the one-upmanship — makes him exciting and fun, but at the same time something of a monster.

At 1:10:18, provoked by Smails, who threatens that he’ll never be allowed to join Bushwood, Czervik lets the cat out of the bag. “You think I’d join this crummy snobatorium? Why, this whole place sucks,” he scoffs. (In those days, “sucks” was considered extremely vulgar language.) “That’s right. It’s sucks! The only reason I’m here is maybe I’ll buy it.” This existential threat leads Smails, whom as we’ve seen is over-identified with Bushwood, to physically attack Czervik. (“I get no respect,” Czervik mutters at 1:10:31, a little meta-joke.) That fracas leads to Czervik proposing the money match, then doubling and redoubling his wager… even though Czervik, as we’ve seen, is not a very good golfer.

Why does Czervik insist on raising the stakes of a game he can’t win? I think the answer is to be found at 1:12:06, when Judge Smails, Dr. Beeper, and a Bushwood honcho chuckle at Czervik’s challenge. His motivation may be an orthogonal one, but at the end of the day even Al Czervik demands respect. “You’re no gentleman,” scoffs Smails. “I’m no doorknob either,” he replies.

There you have it: the second half of Ty Webb vs. Al Czervik, our Caddyshack meaning map’s hermeneutic code. I’ve identified the paradigm Al Czervik’s contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. In doing so, I’ve established not only what Al Czervik means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the character — but how this paradigm means what it means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts to facial expressions, clothing, mannerisms, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what Ty Webb signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

We’ll give the last word to Al Czervik, the character who doesn’t even want to be in Caddyshack: “I should have stayed home and played with myself!”