Nobrow Mickey

In 1971, David Bowie (born 1947) released “Life on Mars?” — one of his best tunes — as a single, as well as on his album Hunky Dory. He explained, at the time, that the song’s protagonist — a sensitive young woman — “finds herself disappointed with reality… that although she’s living in the doldrums of reality, she’s being told that there’s a far greater life somewhere, and she’s bitterly disappointed that she doesn’t have access to it.” One of the girl’s sorrows is articulated like so: “It’s on America’s tortured brow / that Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow.”

The scrappy, witty, trickster-ish MM had turned into someone lame, a drag. It’s also worth noting that the neologism “cash cow” was then brand-new.

As we’ve seen in previous installments in this series, throughout the Sixties (1964–1973) members of Bowie’s generation snarkily savaged MM as a capitalist stooge, and an avatar of American shittiness. However, I’d suggest that Bowie’s take on MM, in “Life on Mars?”, isn’t snarky; it’s mournful. Bowie’s “girl with the mousy hair” is looking back sorrowfully; at a structural level, the song is a rebuttal to the Rat Pack bravado of Sinatra’s “My Way” (lyrics by Paul Anka, set to the tune of the 1967 French song “Comme d’habitude,” a favorite of Bowie’s).

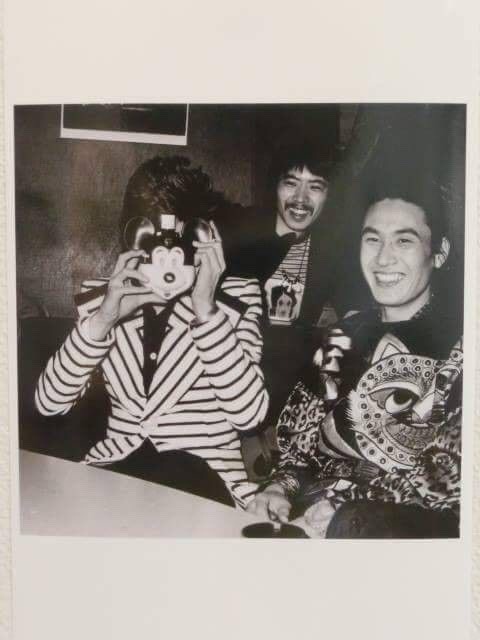

Above: Bowie, c. 1973, with a Mick-A-Matic camera.

I’m including this note about “Life on Mars?” in this installment, as opposed to in the SIXTIES BACKLASH post, because — as always — Bowie was at least a decade ahead of his peers. They were snarky and cruel, when it came to depicting MM; he was ironic — in an engaged, not dismissive, way. He tried a little tenderness. During the cultural era known as the Seventies (1974–1983), as this installment will demonstrate, an anti-Sixties backlash occured within the MM backlash; it became OK, among nobrow cultural creatives following in Bowie’s footsteps, to love MM again… even if, simultaneously, one’s love were expressed in an ironic fashion.

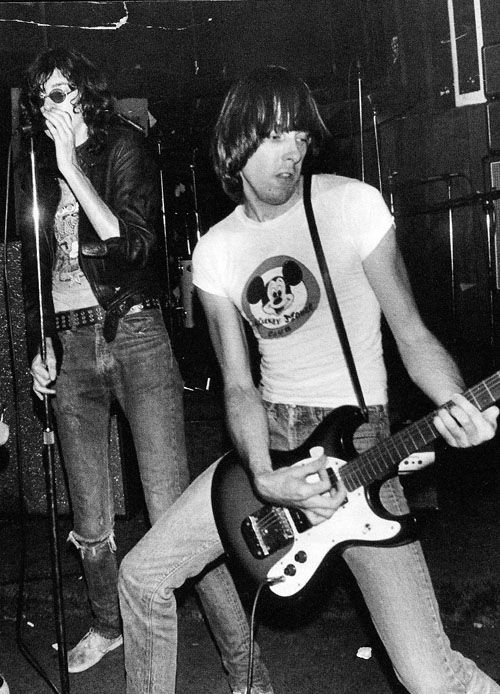

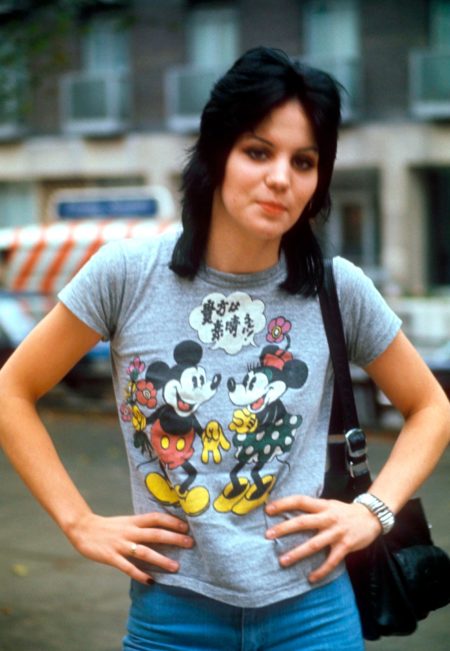

The first years of the Seventies era (1974–1983) saw the birth of Punk, a movement that first developed — thanks to acts such as Television, Patti Smith, and the Ramones in New York, and the Sex Pistols and the Clash in London — from 1974–1976. The Ramones were known for reanimating uncool Fifties-era cultural detritus that their hip peers affected to despise. They brought back bubblegum pop, the 7″ single, leather jackets, straight-legged jeans, and… yes, Mickey (and Minnie) Mouse t-shirts.

If you resent what Mickey has become, but admire what he used to represent, while at the same time despising the sanctimonious Mickey-rejection that characterized the Sixties, how to advertise your complex MM affiliation? For the Ramones, as well as other punks and new wavers in the same milieu, the answer was: wear a Mickey tee, framed by your ripped jeans, chaotic hairdo, and ironic demeanor. The uninitiated might think you’re making fun of Mickey; the clueless might think you’re a Mouseketeer gone to seed. Let ’em wonder.

Andy Kaufman’s “Mighty Mouse” act — performed in NYC comedy clubs in the Seventies — is another excellent example of this sort of put-on.

In Bob Zmuda’s book about Kaufman — specifically about the period when he was doing his “Mighty Mouse” act — he writes, “Was Andy a wide-eyed innocent? Or was he a fearless and subversive outlaw, lampooning the mediocrity of the entertainment industry? To me, his writer for ten years, he was both.”

Let ’em wonder.

The rest of the Seventies (1974–1983) were a weird time, both for MM and MM’s critics — whether snarky or nobrow. Here are a few notes:

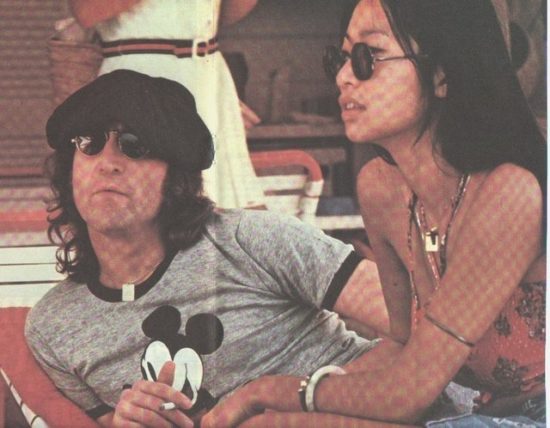

John Lennon and his assistant/lover, May Pang, took Julian Lennon to Disney World for a week in 1974. The trio stayed at the Polynesian Village Resort. While there, and while wearing a Mickey tee, John signed the paperwork officially disbanding The Beatles. Thus officially ending the Sixties.

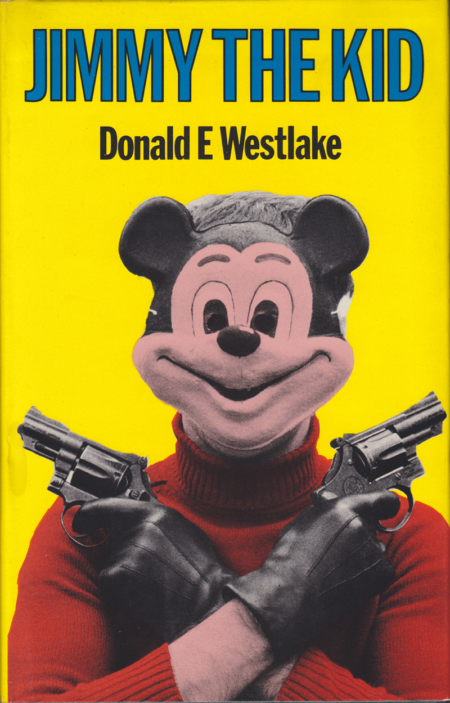

Above: UK hardback first edition of Donald E. Westlake’s Jimmy the Kid, published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1975.

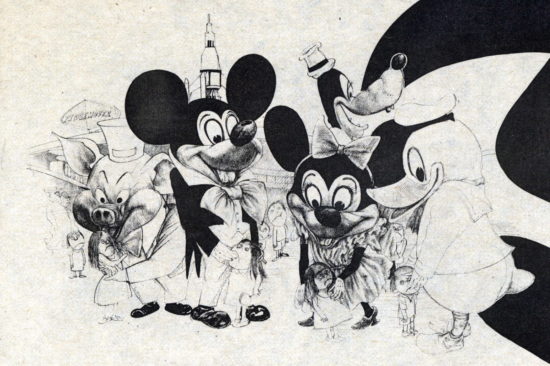

In 1975, the British illustrator Ralph Steadman — whose illustration for Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) we saw in an earlier installment in this series — was sent by Rolling Stone to write and illustrate “Ralph Steadman’s Disneyland”.

In 1977, the Walt Disney studio rebooted the Mickey Mouse Club. The results were unintentionally hilarious.

In 1978, MM turned 50. The 1978 TV event Mickey’s 50, a special 90-minute edition of The Wonderful World of Disney, featured appearances and tributes from Ed Asner, Anne Bancroft, Edgar Bergen, Mel Brooks, Carol Burnett, Red Buttons, Karen and Richard Carpenter, Johnny Carson, Chewbacca, Dick Clark, Bette Davis, Phyllis Diller, Dale Evans, Sally Field, Gerald Ford, Jodie Foster, Kermit the Frog, Annette Funicello, Eva Gabor, Elliott Gould, Rev. Billy Graham, Goldie Hawn, Sterling Holloway, Bob Hope, Bruce Jenner, Elton John, Shirley Jones, Gene Kelly, Christopher Lee, R2-D2, Joe Namath, Willie Nelson, Gregory Peck, Peter Sellers, O.J. Simpson, Burt Reynolds, Kenny Rogers, Roy Rogers, Mickey Rooney, James Stewart, Jan-Michael Vincent, Barbara Walters, Raquel Welch, Lawrence Welk, and Henry Winkler — among others. Weird!

Even weirder: Throughout Mickey’s 50, a three-part live-action/stop-motion short animated by and starring Mike Jitlov seems to suggest that MM memorabilia collectors are actually insane.

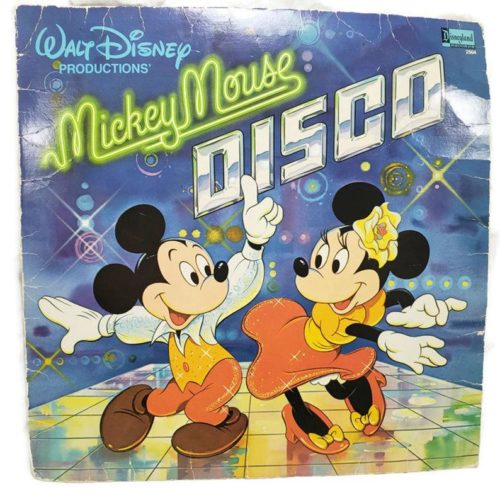

Releasing a 1979 album of disco versions of Disney songs (e.g., “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” “It’s a Small World”) and Disney-fied versions of disco hits (e.g., “Disco Mickey Mouse,” “Macho Duck”), titled Mickey Mouse Disco, sounds like a terrible idea — right? Right. It went double platinum, anyway. A theatrically released compilation cartoon music video of the album was released in 1980. It’s horrible.

In 1979–1981, during the The Iran hostage crisis, images of Mickey Mouse flipping the bird — with the caption “Hey Iran” — became a popular meme.

In 1981, Serge Gainsbourg’s reggae-ish novelty song song “Mickey Maousse” uses MM’s moniker as a euphemism for penis.

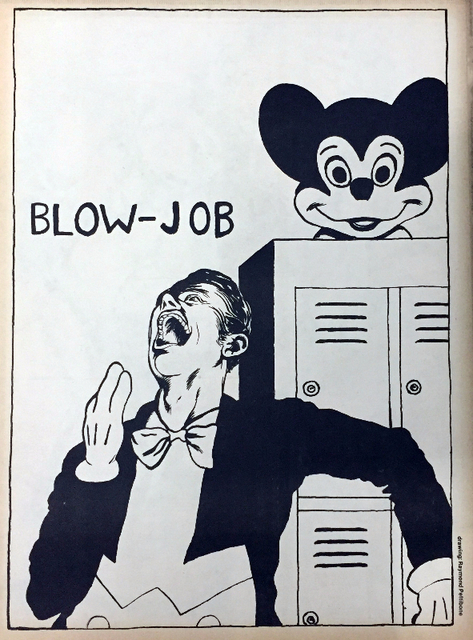

Above: A 1981 artwork by Raymond Pettibon (Raymond Ginn, born 1957), who came to prominence around that time in the southern California punk rock scene. Pettibon was first known for creating posters and album art — e.g., Black Flag’s Family Man, In My Head, Jealous Again; Minutemen’s Paranoid Time, What Makes a Man Start Fires?; — for SST Records, which was owned and operated by his brother, Greg Ginn of Black Flag.

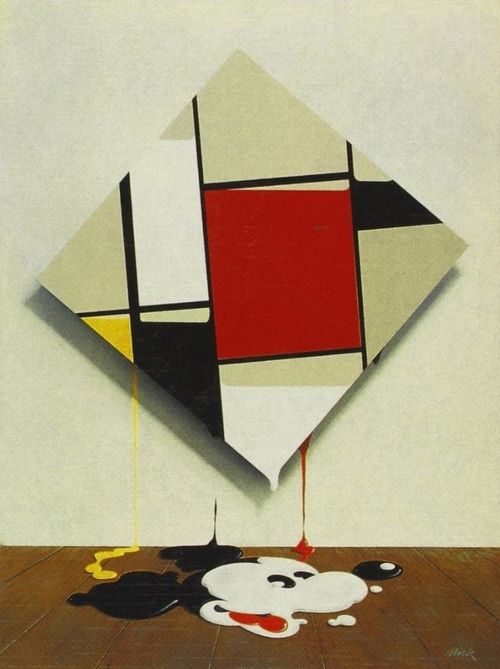

Above: In 1982–1983, when Condé Nast chairman Samuel I. Newhouse brought the long-shuttered café-society magazine Vanity Fair back to life, an early trial cover featured a 1978 painting, “Mickey Mondrian” by English designer and illustrator Mick Haggerty. Haggerty’s album covers — e.g., Pointer Sisters’ Steppin’ (1975), Supertramp’s Breakfast in America (1979), The Police’s Ghost in the Machine (1981), The Go-Go’s’ Vacation (1982), and David Bowie’s Let’s Dance (1983) — helped define the look of the Seventies (1974–1983).

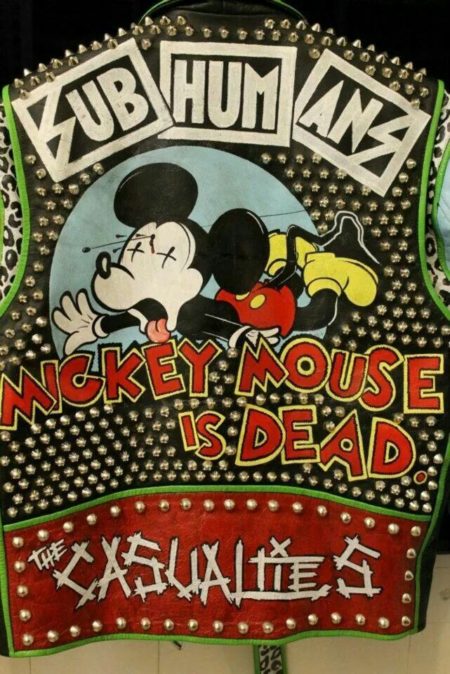

Let’s end this post with an excerpt from “Mickey Mouse Is Dead,” a 1983 song by the English hardcore punk band Subhumans:

Mickey Mouse is dead

Got kicked in the head

Cos people got too serious

They planned out what they said

They couldn’t take the fantasy

They tried to accept reality

Analyzed the laughsCos pleasure comes in halves

The purity of comedy

They had to take it seriously

Changed the words around

Tried to make it look profound

The comedian is on stage

Pisstaking for a wage

The critics think he’s great

But the laughter turns to hateMickey Mouse is on T.V.

And the kids stare at the screen

But the pictures are all black and white

And the words don’t mean a thing

Cos Mummy’s got no money

And Daddy is in jail

He couldn’t afford the license

She couldn’t afford the bailThe kids out in the road

Their minds have all gone cold

Cos Mickey Mouse is dead

They shot him through the head

With ignorance and scorn

They believed in something new

They read the papers watched the films

And they thought they knew the truth

Look what you’ve done to Mickey Mouse

Interesting to note that the Subhumans aren’t taking the piss out of MM, but angrily castigating those who’ve “killed” MM — which is who, exactly?