Taking the Mickey

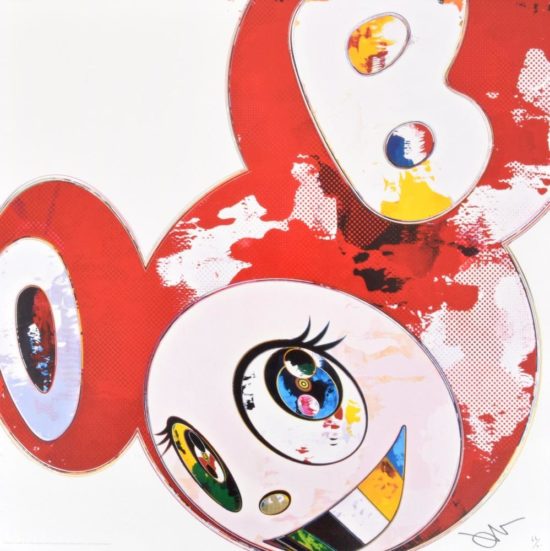

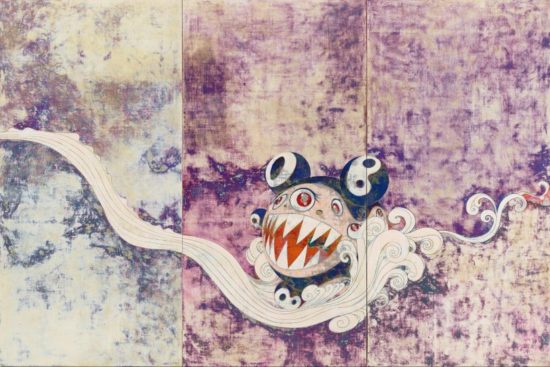

Takashi Murakami’s first character, “Mr. DOB."

If the Fifties (1954–1963) and Sixties (1964–1973) MM backlash expressed — often in an adolescent fashion — rage about what Mickey Mouse had become, and what the character had come to represent (call it: neoliberal hegemony masquerading as aw-shucks pluckiness and cheer), and if the Seventies (1974–1983) showed us how artists could appropriate MM iconography to explore complex negative/positive, personal/political expressions, then ever since then we’ve seen a marvelous proliferation of Mickey’s meaning.

From c. 1984–on, when it comes to deploying MM as a sign or symbol, anything goes. During the past three-plus decades, artists have felt free to reboot aspects of MM’s original aspects (minstrel, trickster, plucky survivor), and to express admiration and affection for MM, safe in the knowledge that audiences will understand that there is some level of irony involved. They’ve also rebooted aspects of the various MM parodies (stoner Mickey, capitalist Mickey etc.), minus the heavy-handed, strident political angst that flattens out parodies and renders them unfunny.

NB: It would be impossible to capture every MM appropriation or parody from 1984 through the present, in this post. I’m not going to try. I’ve just pointed out a few that I particularly enjoy, or which seem important.

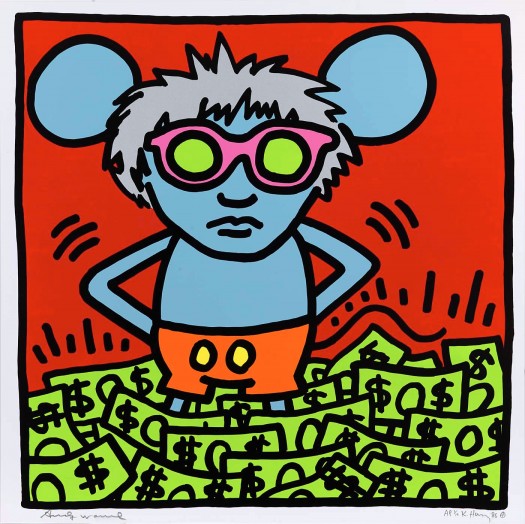

Keith Haring began portraying Any Warhol as a MM figure, c. 1985. The two artists met in 1984, and realized that they both admired Walt Disney.

There is a cargo-cult or Santeria aspect to Haring’s “Andy Mouse” prints. It’s as though Haring has invented a new god, the worship of whom will bring Disney-like financial success to an artist….

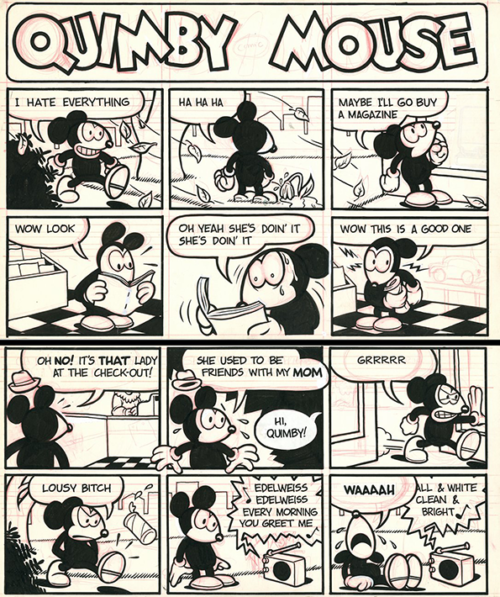

Genius cartoonist Chris Ware created an early version of his Quimby the Mouse character while attending the University of Texas at Austin from 1990-1991.

He experimented with “cartoon faces created more or less by drawing Mickey Mouse without ears,” Ware has recalled, and created a “strip about a lone pale character lost in a landscape of nostalgia.” However, members of the Black Student Alliance found Ware’s earless mouse character, who looked liked a minstrel, racist; the strip was pulled from The Daily Texan.

For his debut in the great comics anthology Raw (“High Culture for Lowbrows”), edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly and published from 1980 to 1991, Ware resuscitated his Mickey-ish mouse for an avant-garde strip called “I Guess” — which is where we first meet Quimby.

Ware is one of the most formally inventive cartoonists working today. His Quimby comics are not to be missed.

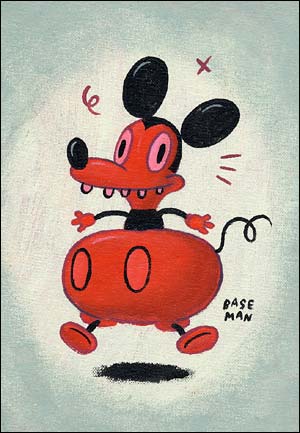

The Art of Mickey Mouse: Artists Interpret The World’s Favorite Mouse (1991), edited by Craig Yoe and Janet Morra-Yoe, is a fun collection of MM artwork commissioned by the editors — as well as a few earlier pieces. Contributors include Charles M. Schulz, Ward Kimball, Ever Meulen, R. Crumb, Jack Kirby, Maurice Sendak, Moebius, Keith Haring, Gary Baseman, and many more. The introduction by John Updike is perhaps the best essay ever written about MM.

PS: The cover of the book features Warhol’s MM screen print, which I find very uninteresting. Seems like a crass attempt, on Warhol’s part, to move some units.

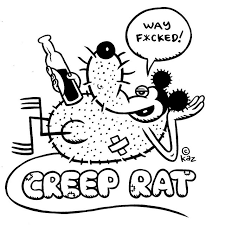

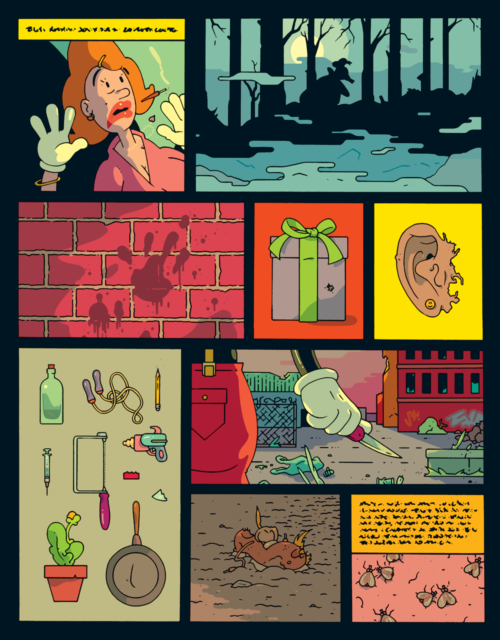

Beginning in 1992, Kaz Prapuolenis, another of my favorite cartoonists from RAW and Weirdo in the Eighties, gave us the character Creep Rat — the murderous, drug-addicted co-star of Underworld. Creep Rat is a descendant not so much of MM, but of Fifties and Sixties-era MM parodies like Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s Rat Fink and Robert Armstrong’s Mickey Rat.

However, unlike these unpleasant freaks, in a perverse way Creep Rat is actually kinda loveable. Like the earliest MM, in other words, he is a resilient, sassy, funny trickster, survivor, criminal and cad; we root for him, despite his debauched way of life and utter lack of social graces.

In the early 1990s, Joyce Pensato began painting drippy, blurred, sinister, yet also scrappy and endearing portraits of Batman, Homer Simpson, and other cartoon characters… including MM.

Pensato once said, during a videotaped studio visit, that she thought Walt Disney had made Mickey Mouse seem “lobotomized.” Her goal was to extract much stronger, more conflicted, feelings from her subject. Above: “Big Mickey” (2007).

In 1995, Walt Disney Feature Animation released the first new MM short in years: Runaway Brain. It’s a macabre story — featuring a possessed MM — which caused a certain amount of consternation among fans, at the time. By the same token, Disney was signaling that they were no longer going to be quite so protective of their mascot.

It’s a pretty clever film, with lots of references: We see MM playing a videogame in which Dopey and the Wicked Witch fight one another; we spot a photo of MM piloting the boat from Steamboat Willie, in his wallet; Zazu from The Lion King (1994) briefly appears; and Jeffrey Katzenberg’s firing from Disney Co. is referenced by a pink slip featuring the initials “JK.”

Takashi Murakami — “the Warhol of Japan” — rejects any distinction between high art and pop culture or commerce. Murakami’s first character, “Mr. DOB,” a sharp-toothed yet playful anime-esque character, was inspired by MM.

Mr. DOB made his debut in the three-paneled painting “727” (1996), which evokes the woodblock prints of the 19th-century Japanese artist Hokusai.

In 1999, the street-art KAWS (Brian Donnelly) created his first toy, “Companion,” a vinyl figure of Mickey Mouse with x-ed out eyes. Produced in an edition of 500, “Companion” sold out almost immediately. Since then, KAWS has built a career toggling back and forth between fine art — sculptures, paintings — and commercially available figures and toys. “Companion” keeps showing up, in new forms.

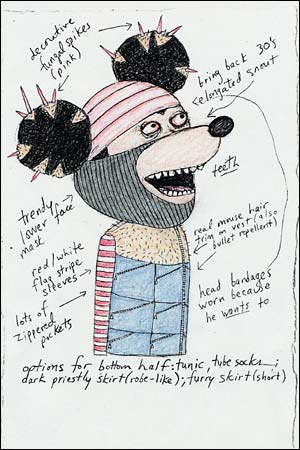

In 2004, the New York Times invited several contemporary artists (including Bruce McCall, Gary Baseman, and Milton Glaser) to reimagine MM. Laylah Ali created the version shown above. “I just think the current Mickey doesn’t give us a reason to stay focused on him,” Ali told the NYT. So she gave him ear spikes, a head bandage, the fur of conquered mice for his vest, and a red-white-and-blue ensemble.

“He is aware that he is a symbol of the cultural inclinations of the United States,” Ali explained, “and he’s not going to fight it.”

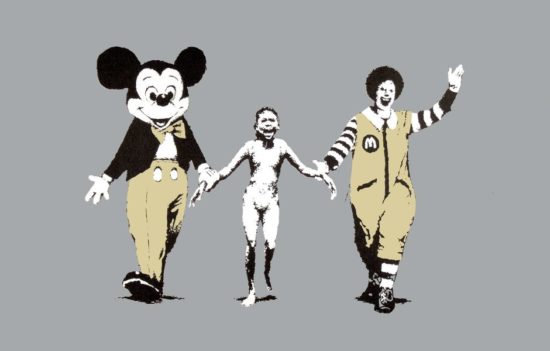

Banksy’s 2004 print Napalm — also known as Can’t Beat That Feeling — is a throwback to the Vietnam War-era MM backlash. According to the website Myartbroker.com: “Prevalent symbols of American commercialism, Banksy uses the characters as an attack on American consumer culture and to reflect upon the dangers of capitalism, its impact on the population, especially children, denouncing its lack of humanism.”

In 2009–2010, beginning with the video game Epic Mickey, Disney began to rebrand MM by emphasizing the cantankerous and cunning aspects of his character.

The New York Times reported, at the time:

Epic Mickey, designed for Nintendo’s Wii console, is set in a “cartoon wasteland” where Disney’s forgotten and retired creations live. The chief inhabitant is Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a cartoon character Walt Disney created in 1927 as a precursor to Mickey but ultimately abandoned in a dispute with Universal Studios. In the game, Oswald has become bitter and envious of Mickey’s popularity. The game also features a disemboweled, robotic Donald Duck and a “twisted, broken, dangerous” version of Disneyland’s “It’s a Small World.”

All of which sounds like a nod to the Fifties MM backlash.

We mentioned, in an earlier post, that in 1970 members of the Youth International Party (Yippies) briefly invaded Disneyland. the painter Bob Dob‘s 2012 solos show at the gallery La Luz De Jesus featured a series of paintings about the fictional Mouseketeer Army — a reactionary guerrilla force fighting to preserve the Magic Kingdom from its enemies.

Since 2013, the Disney Channel has been airing new 3.5-minute Mickey Mouse shorts. Created, written, storyboarded, executively produced, and directed by Paul Rudish, the shorts exude contemporary ’tude while using the character designs and personalities of the earliest MM shorts as their (retro) reference point.

Also: The 2013 Walt Disney Animation Studios short Get a Horse!, which combines black-and-white hand-drawn animation and color CGI animation, and stars the characters of the earliest MM cartoons, is sort of brilliant.

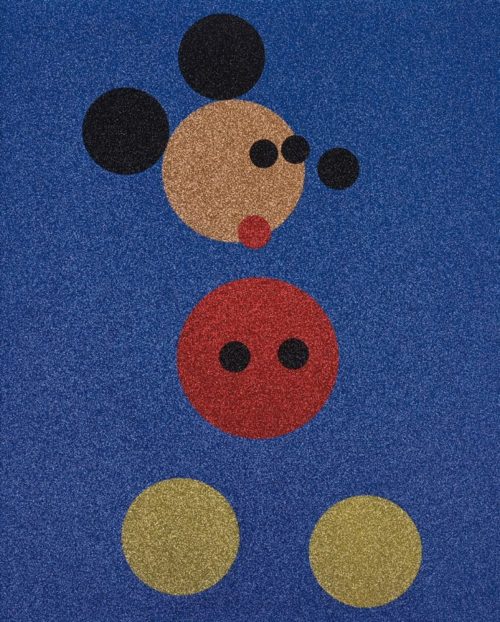

And now for something completely different: Damien Hirst’s 2016 silkscreen print (with glitter) “Mickey.” Hirst explains that his prints of Mickey and Minnie “represent happiness and the joy of being a kid and I have reduced the shapes down to the basic elements of a few simple spots….”

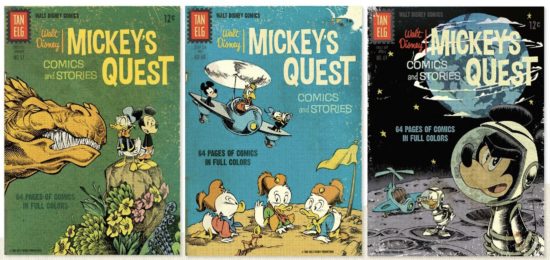

Mickey’s Craziest Adventures, a 2016 provocation by Lewis Trondheim (writer) and Nick Keramidas (artist), features 44 pages from a lost MM comic book, Mickey’s Quest, originally published from 1962–1969. It was supposedly too wild for kiddies, and never saw wide circulation. In fact, there was no such comic.

Tommi Musturi (b. 1975) is a Finnish cartoonist best known for his two comic series Walking with Samuel and The Books of Hope. The above image is from Musturi’s The Anthology of Mind (Fantagraphics, 2019).

Artists today use Mickey’s entire history — including the backlash — as a source for inspiration; they knowingly involve their readers in a potent admixture of nostalgia, irony, love, scorn, and hope.

Mickey Mouse is dead. Long live Mickey Mouse!

Thanks, Jeff Malmberg, Meghan Walsh, and Money Mark for prompting me to undertake this MM research and analysis…