Minstrel Mickey

Walt Disney’s animated Mickey Mouse character debuted publicly in the short film Steamboat Willie (1928). Although Disney never acknowledged this fact, it’s clear that aspects of the character’s appearance evolved from the blackface caricatures used in minstrel shows. More precisely, aspects of Mickey’s appearance evolved from earlier cartoon characters, which themselves were referencing 19th century blackface caricatures that had survived in early 20th century vaudeville.

The tradition of minstrelsy — an American form of racist entertainment developed in the early 19th century — lampooned black people as dim-witted, lazy, and buffoonish, though also, and FWIW, happy-go-lucky and subversively clever. The physicality of blackface minstrel characters is “fluid, voracious, and libidinal,” according to one historian. Around the turn of the 20th century, the minstrel show began to be replaced by — and incorporated into the structure (e.g., gags and puns, “hokum” songs, proto-standup comedy) of — vaudeville.

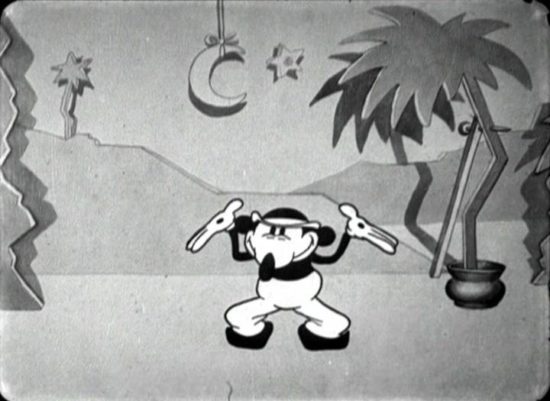

Like Fleischer’s Bimbo the dog, Sullivan and Messmer’s Felix the Cat, and Universal’s Oswald the Lucky Rabbit (created, on a work-for-hire basis, by Disney and Ub Iwerks), among other animated film characters who preceded him, Mickey had a black body and head, large eyeballs, and a partially white face. (The white gloves, also a staple feature of minstrelsy, came later.) One can also point to the offensive Looney Tunes character Bosko, who was supposed to be a “Negro boy.” Bosko’s popular catchphrase: “Mmmm! Dat sho’ is fine!”

The Nov. 5, 2019 episode (“‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,’ Minstrels in Hollywood and The Oscars”) of Karina Longworth’s podcast “You Must Remember This” helps us get more granular. Here, we learn that the song “Zip Coon,” whose melody is derived from the folk standard “Turkey in the Straw,” dates to the early 1830s. The song, and a character called Zip Coon, became major features of minstrel shows. Historians of minstrelsy note that the 1946 Disney song “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” likely refers to “Zip Coon.”) Whereas the character Jim Crow was a dancing, singing black field-hand who avoided work, “Zip Coon was usually a free man, a caricature of an ‘uppity’ African American who fancies himself smarter and more refined than Jim, but is revealed to be just as bumbling and ignorant.” He may look like a sophisticate, but Zip Coon is an example of the “coon” stereotype — a flamboyant trickster who avoids work and pursues maximum leisure.

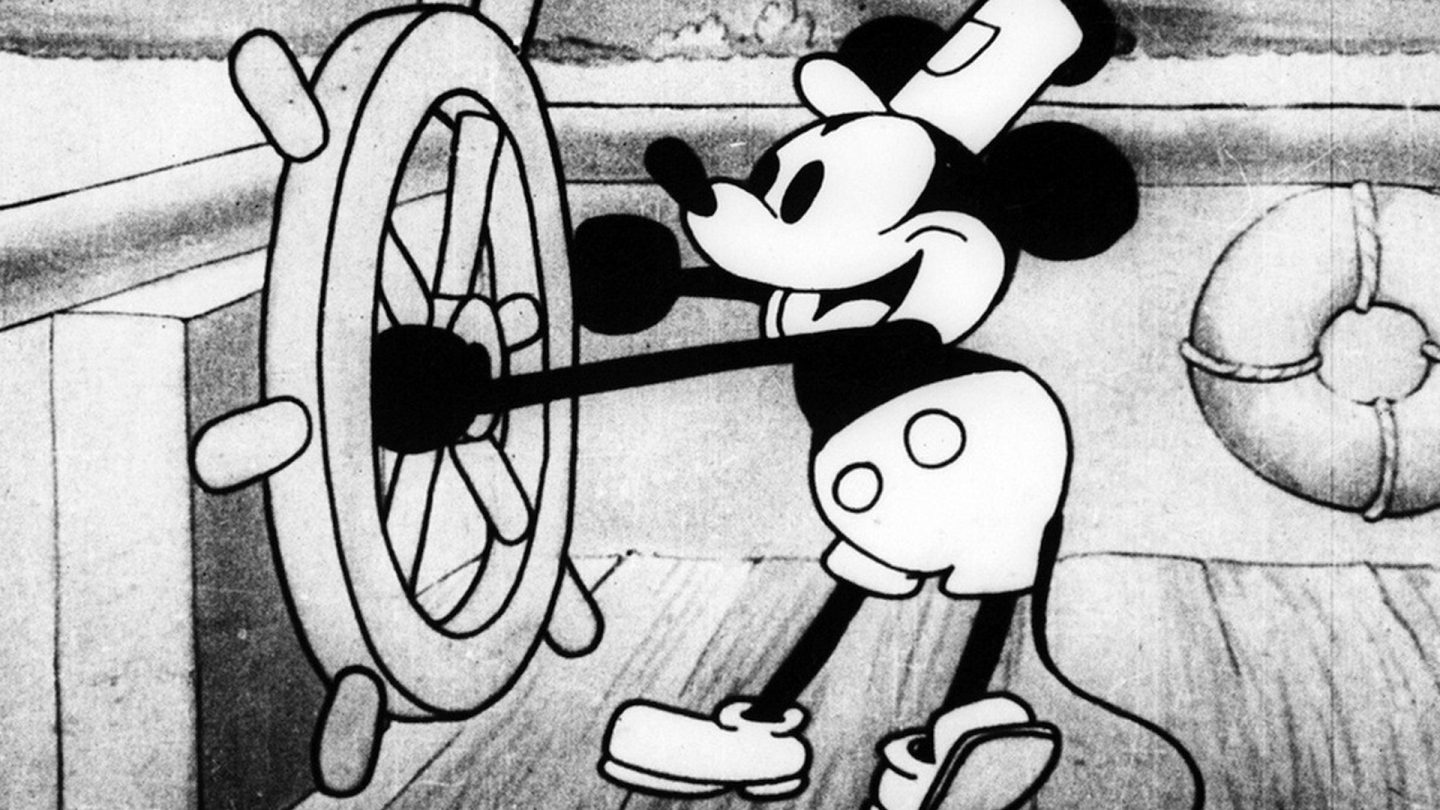

In Longworth’s discussion of Steamboat Willie (1928) and other early MM cartoons, she notes that Mickey and his friends were associated with minstrelsy thanks to “their big bug eyes and their white gloves, which were often worn in minstrel shows by dandy characters, as a signifier that they aspired to a higher class.” She also notes the use of “Turkey in the Straw” in Steamboat Willie — a song which had since “Zip Coon” become closely associated with minstrelsy. “So from the beginning, Disney sought to take up the tropes of this other form of popular culture.”

Mickey’s appearance, his bodily plasticity, his subversive mischief-making, even his ability to absorb punishment suggest that the character’s appeal tapped into America’s fondness for minstrelsy. So even if indirectly and relatively inoffensively (he wasn’t dim-witted, lazy, or buffoonish; he didn’t speak in “black” vernacular), Mickey Mouse’s 1928 origin was racist.