Trickster Mickey

There’s a certain animile, making everybody smile. What’s this fellow’s name? Mickey! Mickey! Tricky Mickey Mouse!

— 1930 song by Harry Miles

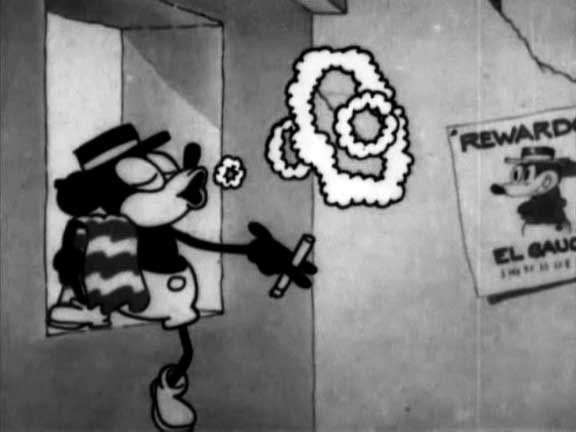

From 1928 through c. 1933, which is to say through what I’d call the second half of the cultural era known as the Twenties (1924–1933), Mickey Mouse was a rogue, a prankster, sometimes even a jerk. As noted in this series’ first installment, MM’s persona is indebted to that of minstrelsy’s roguish, work-averse, libidinal “coon” character. In Mickey’s earliest cartoons, he is 100% concerned with “getting over” — that is to say, doing just enough work to keep from being fired. In his earliest appearances, Mickey drinks beer, smokes, lusts after Minnie Mouse, and lives by his wits. He is petty and vengeful, looking for ways to one-up anyone who annoys him.

However, within just a couple of years, Walt would begin a whitewash campaign to make us forget the original Mickey. How? He began to spread the story that Mickey’s personality was modeled more or less entirely after Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp character.

A 1931 piece by Harry Carr quotes Disney saying, “We wanted something appealing, and we thought of a tiny bit of a mouse that would have something of the wistfulness of Chaplin… a little fellow trying to do the best he could.” Ever since, Mickey has been described as “a graphic analogue to Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, trying to get by (and have a little fun) in a not-always-friendly world,” to quote Garry Apgar’s Introduction to A Mickey Mouse Reader. Yes, there’s something to the Chaplin-Mickey comparison, but let’s dig into this a bit. It’s not nearly so simple as that.

Alva Johnston, writing in 1934, noted that although Chaplin and Mickey may “have the same blend of hero and coward, nit-wit and genius, mug and gentleman,” Mickey lacks “the emotional subtleties of Chaplin, his repose, wistfulness and pathos.” This is a key insight: Mickey was not, at least at first, a sentimental figure. We learn nothing from Mickey, he isn’t inspiring. Writing in 1934, the highbrow novelist E.M. Forster indicates that this is exactly why he likes Mickey Mouse, as opposed to middlebrow cinema: “Here [in the movie theater] art is not, life is not. Not happy, not unhappy, I sit in an up-to-date stupor, while the international effort unrolls.” Mickey, however, is “energetic without being elevating. No one has ever been softened after seeing Mickey or has wanted to give away an extra glass of water to the poor. He is never sentimental, indeed there is a scandalous element in him which I find most restful.”

Scandalous: Mickey was shocking, outrageous to settled norms. The same could not be said of Chaplin’s Little Tramp.

Mickey Mouse was also outrageous to settled forms. An antic hodgepodge of rubbery limbs and round body parts, at the level of form the Mickey character is incommensurable. He isn’t fungible. Literally and figuratively, Mickey is a round peg that won’t fit into a square hole. Like Silly Putty, a Super Ball, a Slinky, a Crazy Straw, Mickey’s form is not useful or educational; it is weird, funny, eccentric, scandalous.

America, in the early 20th century, was the source of Fordism — the mass production of standardized goods on a moving assembly line. Mickey is an anti-Fordist homonculus. He serves as a rebuke to standardization, to efficiency. Note that Chaplin wouldn’t be sucked into factory equipment, in Modern Times, until 1936.

When C.A. Lejeune, the first female British film critic, admiringly wrote, in 1929, that “the whole cunning of Mickey lies in its deliberate sub-tones — it is a whispered and wicked commentary on Western civilization,” she was voicing the highbrow’s (anti-middlebrow) appreciation for the comic, carnivalesque lowbrow. Gilbert Seldes, writing in The New Yorker, in 1931, describes MM as a trickster figure: “In the current American mythology, Mickey Mouse is the imp….”

The credit for early Mickey’s impish physicality must go to Ub Iwerks, who first drew and animated Mickey. One of his colleagues noted that Iwerks’s cartoons “swing” — his syncopation, his gift for extending rhythmic lines, distinguished Iwerks’s animations from all the rest.

John Canemaker, writing in the New York Times in 1995, described MM’s original look like so: “A white mask on a black circular head with pie-shaped eyes, two smaller ear-circles and two-button short pants on a round black body. But Mickey was also a grungy, goggle-eyed, long-snouted ratlike creature, with tubular arms and legs, no gloves, no shoes and no class.”

Edwaard Lewine, writing in the same newspaper in 1997: “He was scrawny, with a long, sinister face. His hands and feet knew neither glove nor shoe and he spoke in funny noises, not words. And he was a mean guy.”

Maurice Sendak, on MM: “He was a malignant little creature in the beginning, which is why he was so charming.” In a 2004 New York Times interview, Sendak would elaborate: “His character was the kind I wished I’d had as a child: brave and sassy and nasty and crooked and thinking of ways to outdo people.”

Gravity Scofflaw

The French famously love American figures — Edgar Allan Poe, Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, Jerry Lewis, Philip K. Dick — whose work rebukes, at the level of form, remorseless American-style efficiency. They were early adopters of Mickey Mouse. A 1929 article in the Parisian monthly Jazz: l’actualité intellectuelle exults, “Never have pictures achieved greater, more varied effects, never has freer rein been given to lively antics and subtle humor.” In a more philosophical vein, the article asks: “Where are we, if not somewhere in the uninhibited world of dreams, in the lawless realm of inanimate objects?”

“Society’s most natural ally in maintaining law and order, conformity, and the institutions that relegate freedom to a perpetual utopia,” claimed Herbert Marcuse at midcentury, is resignation to the subjective tyranny of time and space. Mickey Mouse knows no such resignation. A 1930 article by Creighton Peet titled “Miraculous Mickey” exults that MM cartoons “are ‘free’ in the fullest and most intelligent sense of the term. They know neither space, time, substance nor the dignity of the laws of physics.” Writing in the New York Times in 1935, L.H. Robbins said of Mickey: “He suspends the rules of common sense and correct deportment and all the other carping, conventional laws, including the law of gravity, that hold us down and circumscribe and cramp our style.” And Graham Greene, writing in 1935 about Fred Astaire, noted that with his “quick physical wit, his incredible agility,” Astaire — who might almost be a character created by Disney — “belongs to a fantasy world almost as free of Mickey’s from the law of gravity.”

Mickey’s rubbery form made him an emblem of a free-wheeling, fast-thinking, adaptable mode of living — which, during the Depression — must have been extremely attractive.

Innocent

For all this talk of scandal, impishness, wickedness, though, Mickey was an innocent figure — a childish grownup, one who may smoke and drink but who has somehow avoided becoming resigned to the way-things-just-are. Neither man nor mouse, child nor adult, Mickey is fascinatingly feral. “Childhood is cannibals and psychotics vomiting in your mouth!” Maurice Sendak — an exact contemporary, and fan, of Mickey’s once said in an interview with Art Spiegelman. What Sendak means is that childhood is feral; it’s innocent and wicked, sweet and scandalous. Like Mickey.