Bonnie and Clyde

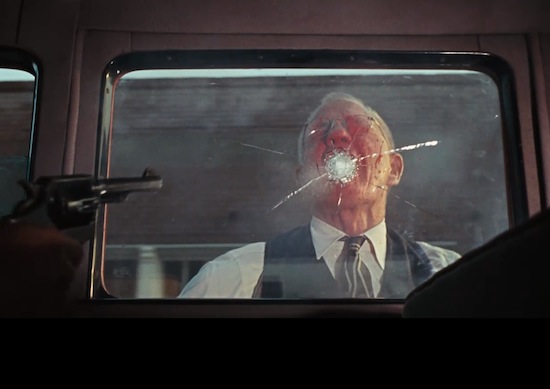

The violent scene, in Bonnie and Clyde, in which the formerly nonviolent Clyde (Warren Beatty) shoots an unarmed bank manager who has leaped onto the running board of the getaway car, is a tragic turning point. Why does Clyde pull the trigger? Arthur Penn’s blocking answers that question.

Like Apocalypse Now, Bonnie and Clyde is a movie whose theme is the experience of moviegoing. Bonnie (Faye Dunaway) flees life’s prison (symbolized by the bars on her bedstead) in Clyde’s stolen cars, whose windshields and windows function as projection screens; at these “movies,” she loses it — that is, her provincial worldview. So when a small-town authority figure blocks the screen, threatening to spoil the experience of watching the slapstick caper movie we’d all been enjoying, Clyde reacts instinctively.

Pauline Kael’s career-making defense of Bonnie and Clyde against its detractors was also a violently instinctive reaction. This movie — insisted the critic born on a chicken farm — is a getaway car: “Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in [our 1930s] childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours — not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours.”

In the following scene — set in a movie theater — while Clyde agonizes about the shooting, Bonnie munches popcorn… and gazes raptly at the big screen.