Stimuli Research

Kind website image

This is the second post in a series demonstrating the process via which Semiovox’s interpretative inquiry produces insights and inspiration — richer and deeper than what consumer research alone can provide — regarding a product category’s or cultural territory’s unspoken meanings.

Now that we’ve settled on our audit’s stimulus set, we’ll move on to stimuli research.

Having agreed upon the stimulus set (see previous post in this series), the next phase of our audit involves research. For each brand in the audit’s stimulus set, Semiovox’s researchers will source packaging examples, as well as brand-generated social media posts, brand website screenshots, advertising (print, digital, TV, YouTube videos), in-store displays, and more.

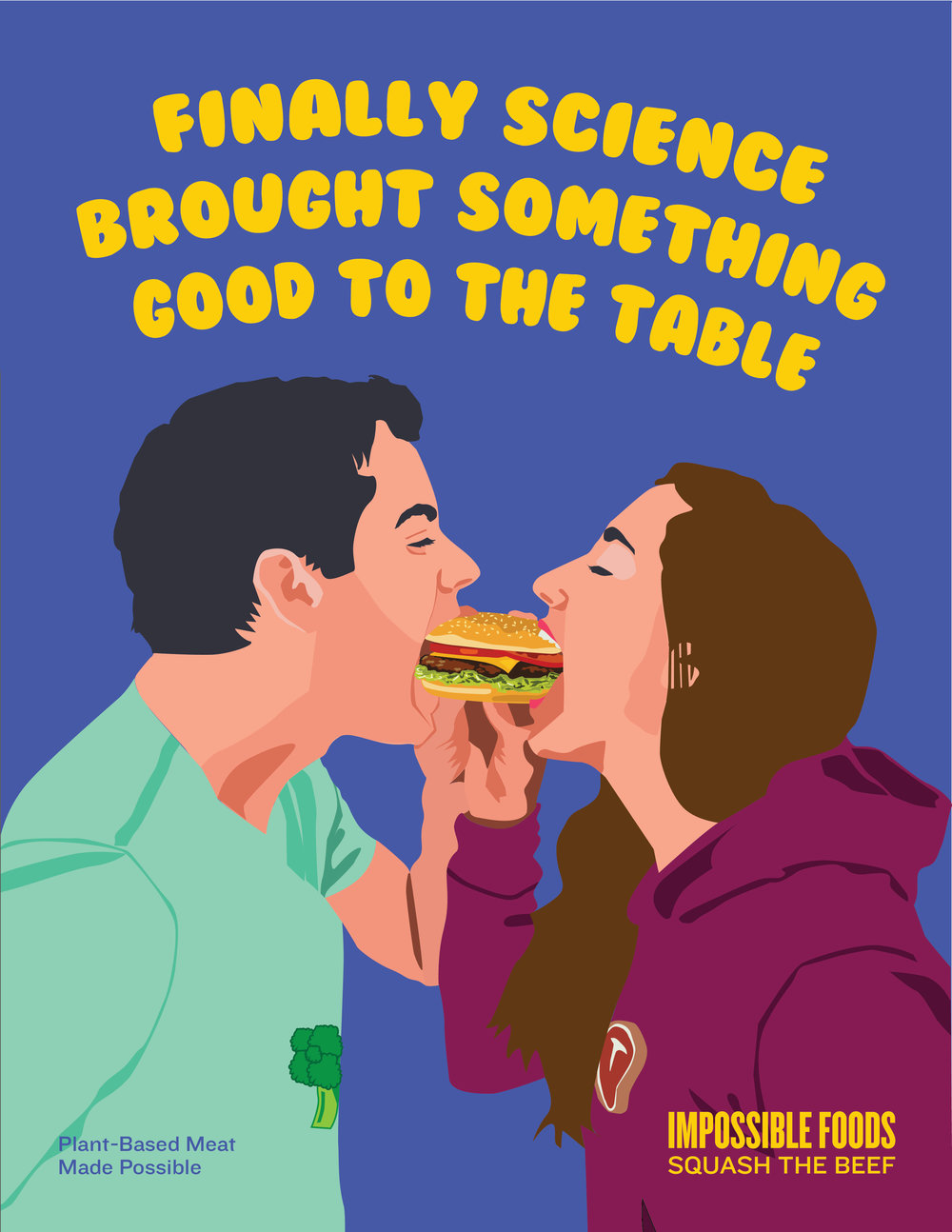

Impossible Burger ad

Kind pack

Stonyfield social

Hormel Natural Choice website

NB: For synchronic audits concerned with painting a picture of what’s currently happening in a category, we’ll only consider current and recent — going back one year, maybe two — stimuli. For diachronic audits concerned with understanding how the category has changed over time, we’ll gather current and recent stimuli and also older stimuli, for comparison’s sake.

What about user-generated social media? We often include social media generated not by the brand, but by fans and critics of the brand. Through research partners, we can deploy social media listening tools; we can also search hashtags, look through recent photos uploaded by users to brand Facebook pages, etc., etc. User-generated social media is interesting and useful, though (a) not necessarily as eye-opening as one might imagine, since consumers tend to “play back” brand messaging [e.g., Coors fans often post photos of Coors cans in Western, mountainous, old-fashioned scenes], and (b) the process of gathering it can be expensive and time-consuming. That said, when we conduct culture audits, as opposed to category audits, user-created social media can be a very valuable source of stimuli.

We typically gather 25–40 pieces of stimuli per brand, so if we’re including 30–50 brands [the Real Food audit includes ~40 brands] in our stimulus set, then we’re talking about a total of anywhere between 750 – 2,000 pieces of stimuli to be analyzed. We’re maximalist in our research, for two important reasons:

- The more stimuli, the more we discover about the category’s explicit and implicit norms (ideas, values, higher-order benefits) and the particular forms (imagery, language, design cues, facial expressions, color schemes, etc.) bringing these category norms to life.

- For those clients who suspect that semiotic analysis is “mushy,” which is to say overly subjective, it can be reassuring to see that we’re not just pulling themes and codes out of thin air; our process requires time and effort.

We like to store each audit’s stimuli on Dropbox, sorted into folders by brand. This not only allows our team to see everything easily, but we can invite our clients to take a look, too.

How do we deal with TV commercials and YouTube videos? We watch scores of them, then take screenshots of particularly important/telling moments. We save the screenshots along with a link to the video itself. We’ll also take note of language from the commercials and videos, as well as notes on other relevant details, such as music, tonality, editing, etc.

Our research process is exhaustive. On top of that, we’ll upload the stimuli —again, anywhere from 750 to 2,000 pieces — to our database, known internally as the Semiodex. Each piece of stimuli is titled, dated, and meta-tagged according to category, higher-order benefits, and more. Phew!

Once we’ve finished gathering stimuli, our initial analysis of the stimuli can begin.

Next Step: THIN DESCRIPTION

A note on Semiovox’s unique approach: Each of our audits surfaces eight paradigms, paired into four binary codes. (A semiotic code is always a binary opposition — two paradigms, each of which is defined in and through its opposition to the other.) Each paradigm is composed of two contrasting thematic complexes; each of these complexes is dimensionalized by source codes (aka signs); and each source code is composed of a norm and a unique visual/verbal form which brings that norm to life. Our methodology involves first identifying source codes from within the stimuli we’ve researched, then — through our meta-analysis of these signs — building a theory about the matrix of meaning which, operating below the level of daily consciousness, enables members of a culture to intuitively “make sense” of everything from brand communications to pop culture, social media, and retail spaces.