Neotonic Mickey

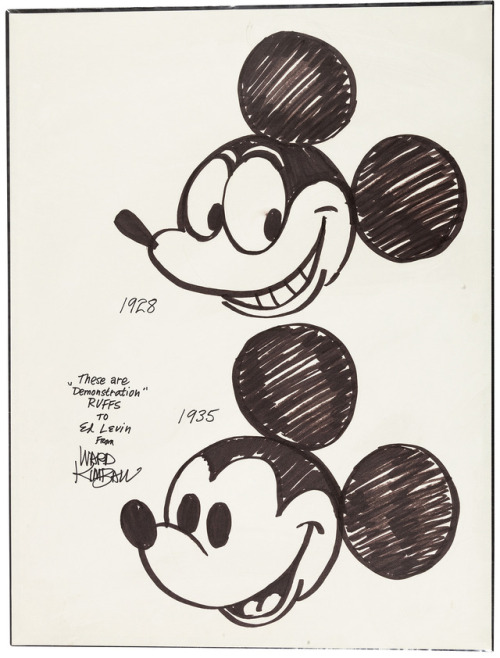

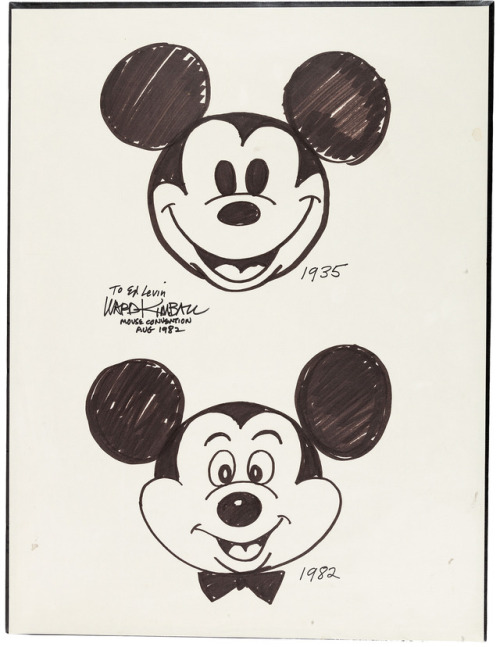

As mentioned in the previous installment, the process of transforming Mickey into an icon, which began c. 1934 with the sanding-down of Mickey’s persona, was completed in 1938 when Disney animator Fred Moore redesigned the character’s look.

“We have taken for granted even Mickey himself,” Harvard art professor Robert D. Feild noted, in his 1942 book The Art of Walt Disney, “without questioning the source of his power. We accepted Mickey so wholeheartedly that for years the idea never entered our heads that he was other than a fascinating cartoon character. We marveled at his antics and the ingenuity with which he went through his paces; we failed to realize” — here Feild’s tone turns rather ominous — “the hypnotic power he was beginning to exert on us.”

What was the source of MM’s hypnotic power, in the years (c. 1938–1942) just before Feild’s book was published?

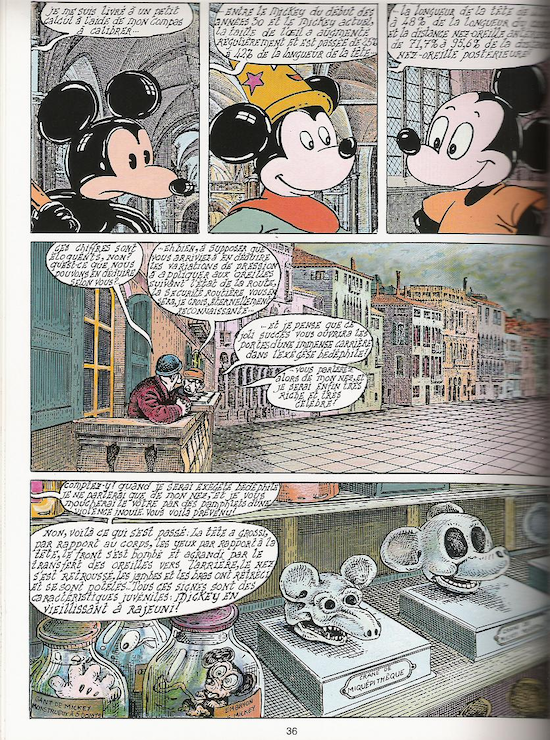

In a brilliant 1979 essay in Natural History, the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould turned his attention to Mickey’s transformed appearance. “Many Disney fans are aware of [Mickey’s] transformation through time,” Gould mused, “but few (I suspect) have recognized the coordinating theme behind all the alterations — in fact, I am not sure that the Disney artists themselves explicitly realized what they were doing, since the changes appeared in such a halting and piecemeal fashion.” Taking measurements — Mickey’s eye size as a percentage of head length, increasing head length as a percentage of body length, and increasing “cranial vault size” — Gould concluded that, over time, “Mickey became progressively more juvenile in appearance.”

Gould deploys these changes to MM to illustrate the (real) evolutionary phenomenon known as “neoteny,” or “progressive juvenilization.” Human children, compared with adults, possess a relatively large head attached to a medium sized body with dimunitive legs and feet. As the years passed, Mickey’s form became more childish: His head grew larger in comparison with his body; his eyes grew larger; his ears moved back, away from his nose, giving him a rounded forehead. “To give him the shorter and pudgier legs of youth,” Gould noted with grudging admiration, Disney artists “lowered his pants line and covered his spindly legs with a baggy outfit.”

What explains this “creeping juvenility”? Gould points to the work of the Nobel Prize-winning Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz, in which we discover the theory that features of juvenility trigger “innate releasing mechanisms” for affection and nurturing in adult humans. “When we see a living creature with babyish features,” Gould notes, “we feel an automatic surge of disarming tenderness.” Whether or not they intended to do so, Disney artists made Mickey’s features more tenderness-inducing. “I submit that Mickey Mouse’s evolutionary road down the course of his own growth in reverse reflects the unconscious discovery [that the features of human childhood elicit powerful emotional responses in us] by Disney and his artists.”

Although Gould signs off his essay with a jaunty “happy 50th birthday” wish to Mickey Mouse, it’s clear that he doesn’t approve of these changes. The earlier, child-like but not childish Mickey was far superior — at the level of form.

Francis Masse’s 1985 comic Les Deux de balcon (1985), which riffs on Stephen Jay Gould’s essay, involves a visit to a Natural History of Neoteny “Mouseum.”

The great children’s author-artist Maurice Sendak (born 1928), writing in TV Guide in 1978, agrees with Gould: “The golden age of Mickey for me is that of the middle ’30s,” he writes — that is to say, pre-1938 redesign. “An ingenious shape, fashioned primarily to facilitate the needs of the animator, [Mickey] exuded a wonderful sense of physical satisfaction and pleasure — a piece of art that powerfully affected and stimulated the imagination.”

MM’s regression to a “shapeless, mindless bon vivant,” Sendak carps, “pushed Mickey out of art into commerce. (Mickey, surely, was always commercial, but now he looked commercial.”) Sendak’s essay concludes with a fervent wish that Mickey would declare his independence “by demanding back the original idiosyncratic self that prosperity and indifference have robbed him of.”

It’s worth noting that Sendak, who was born the same year as Mickey, decided to become an artist after seeing Fantasia. In his TV Guide essay, he reveals: “Playing the Kafka game of shared first initial with most of the heroes in my own picture books [e.g., Max in Where the Wild Things Are (1963)], I only once broke cover and fused a very particular character with the famous Mouse. That is the Mickey who was the hero of my book In the Night Kitchen, written in 1970. It seemed natural and honest to reach out openly to that early best friend while eagerly exploring a very private, childhood fantasy.”