Donald Steals the Show

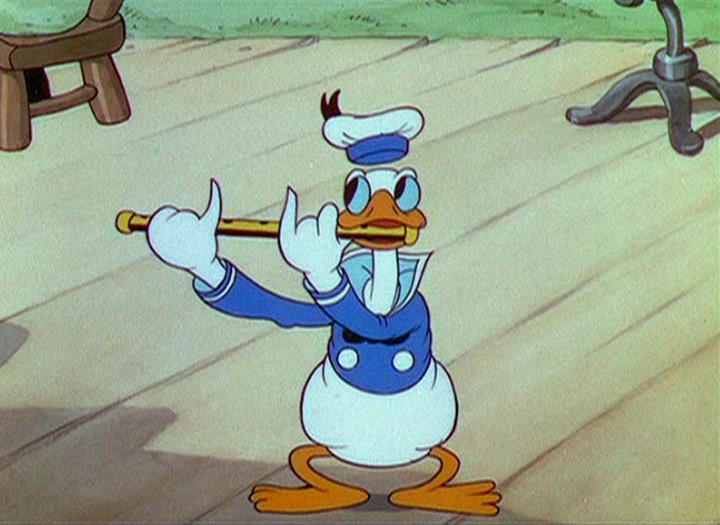

Within the last year, Donald Duck, a ferociously funny animated quackling in Mickey Mouse comedies, has emerged as a serious contender for Mickey’s popularity crown.

1936 Literary Digest essay

“Wo Es war, soll Ich werden.” “Where id was, there ego shall be,” Freud wrote triumphantly in 1933. In 1939, however, Freud would theorize the “return of the repressed” — that is to say, he now recognized that although the ego may fight off an instinctual impulse, at some later date that same impulse will cunningly renew its demand in a distorted fashion… and in doing so, triumph. Why did he change his mind?

Freud’s optimism regarding the ego’s victory over the id was tempered, no doubt, by the rise of Nazism. He didn’t want to believe that the Nazis would succeed in their efforts, so he stayed in Vienna even after they’d invaded Austria, and seized his property. (Freud’s books were burned by Nazi sympathizers as early as 1933; the Gestapo propagandized against psychoanalysts, whose fixation on the id’s uncivilized impulses seemed to undermine the dignity of the Volk.) He didn’t leave Vienna until 1938, three months after the German Army had entered the city and arrested his daughter, Anna. He died in 1939, three weeks after the start of the Second World War.

Perhaps Freud was also chastened by Donald Duck’s triumph over MM, during the Thirties (1934–1943, according to HILOBROW’s well-known periodization schema).

Donald Duck’s first appearance was in 1934. His second appearance, later same year (in Orphan’s Benefit), introduced him as a temperamental comic foil to Mickey Mouse. The lazy, irascible, pranksterish DD would play a recurring role in Mickey’s cartoons from that point forward. In fact, he’d quickly steal the show from Mickey — who as we’ve seen had by 1934 become a role model for children.

That is to say: The formerly lazy, irascible, pranksterish Mickey Mouse was now playful, optimistic, spunky, determined; where id was, only ego remained. But Mickey’s repressed characteristics had returned… in a deformed (duckbilled) fashion!

Because Donald’s stories were more fun to write than Mickey’s, he — along with Mickey’s, clumsy, dimwitted pal Goofy — became the not-so-secret star of Mickey’s movies. The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould notes that whereas Mickey’s features become more juvenile, as the character became more innocent and wholesome, “Donald, having inherited the mantle of Mickey’s original misbehavior, remains more adult in form with his projecting beak and more sloping forehead.”

Disney’s story writers had come to favor DD over MM, and they weren’t above making meta-textual references to their behind-the-scenes maneuvers. In The Band Concert (1935), Magician Mickey (1937), and near the end of Symphony Hour (1942), for example, Donald is portrayed as being jealous of Mickey — desiring to usurp his role as Disney’s biggest star. In 1955, when Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman’s “Mickey Rodent!” comic permitted a vengeful Mickey to triumph over his successful rival, “Darnold Duck,” Mad readers would’ve gotten the joke.

By 1936, Mickey Mouse’s popularity had waned so greatly that Walt decided to produce The Sorcerer’s Apprentice — a deluxe cartoon short based on the poem written by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and set to the orchestral piece by Paul Dukas — as a comeback role for Mickey. As production costs mounted, it became clear that the ambitious short could not be profitable. In 1938, Disney decided to expand The Sorcerer’s Apprentice into a film consisting of eight animated segments set to pieces of classical music.

Fantasia was released in late 1940; initially, it was a flop. It wouldn’t become profitable until 1969, when the movie was promoted to teens and college students with a psychedelic-styled advertising campaign.

In a 2004 New York Times story, Jim Hardison — creative director of a company that revitalizes bygone cartoon characters — describes Fantasia as “the crossover point where Mickey’s story morphed into the Disney [Company] story.” We’ll talk about MM as Disney mascot in a future installment of this series; for the moment, we’ll let Hardison explain himself:

[Fantasia] is where [Mickey Mouse] cemented his place as the source of Disney magic. Magic is such an important characteristic of Disney, but it wasn’t an important characteristic of Mickey. Once he becomes magical, he is no longer the everyman underdog. He went from being the little guy against the world to a symbol of what Disney does.

One more note about Mickey’s eclipse during the second half (1938–1943) of the cultural era known as the Thirties:

In a key scene from Preston Sturges’s 1941 movie Sullivan’s Travels, Joel McCrea’s director character John L. Sullivan, changes his mind about making movies of “social significance” after he witnesses how much pleasure prisoners get from watching a MM movie. Even here, though, MM fails to reclaim his place in the spotlight.

The antics that get the crowd roaring — which inspires Sullivan to realize “there’s a lot to be said for making people laugh… in this cockeyed caravan” — aren’t Mickey’s but Pluto’s.

I should take note, here, of Robert Lawson’s excellent kid’s historical novel Ben and Me (1939). It’s a life of Benjamin Franklin as told by his mouse, Amos, to whom Franklin seems to have been indebted for some of his most brilliant ideas. Like the early MM, Amos is prideful, opinionated, and ingenious; it’s interesting to see this sort of character appear at the apex of the Thirties — just as MM is losing his way.

Also: Mighty Mouse, the animated superhero character created by the Terrytoons studio for 20th Century Fox, first appeared in 1942. Originally named Super Mouse, this MM was a parody of Superman. The cartoons, which spoofed the cliffhanger serials of silent films as well as classic operettas, continued to appear through 1961. Did 20th Century Fox see an opportunity to succeed, with theatergoers, where Mickey Mouse was beginning to fail?