Fifties Backlash

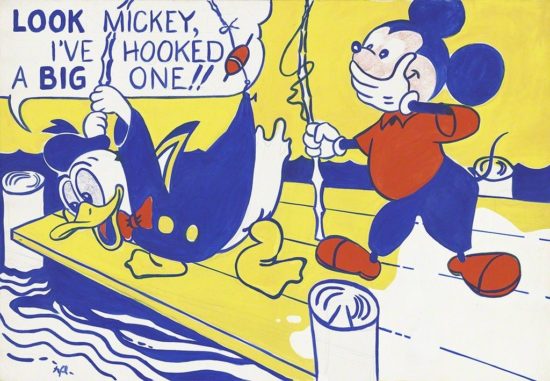

Roy Lichtenstein's Look Mickey (1961)

During the cultural era known as the Fifties (1954–1963), Mickey was “an ambassador of mass culture,” as Lorna Owen puts it in Mouse Muse: The Mouse in Art; as such, Disney’s iconic mouse became “an all too easy symbol for the menace of the Corporation, for cultural imperialism.”

Also, Walt Disney — who in previous and subsequent decades mostly stayed mum about his politics — was active in support of conservative republican candidates, during the Fifties. He sought donations for Eisenhower’s presidential campaign in ’56, and his studio produced the first animated TV commercial for Ike. The motorized cart Walt drove around the Disney studio featured bumper stickers supporting Goldwater and Nixon. He donated to Goldwater’s campaign for president, and offered him the use of the Disney plane.(*) These activities no doubt contributed to the MM backlash of the Fifties.

Fun fact: Although the pejorative phrase “Mickey Mouse” — meaning petty, trifling, not worth the effort — dates to 1930s jazz slang, during the Fifties it went mainstream among servicemen and then the general US population.

Before we get started, it’s important to point out that — for the most part, it seems to me — these satirical anti-Mickey expressions are coming from a place of frustrated love. Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, Roy Lichtenstein, and others who parodied or poked fun at Mickey from 1954–1963 didn’t hate the character. They admired and missed what he once represented — wit, anarchic playfulness, elasticity — and lamented what he’d become.

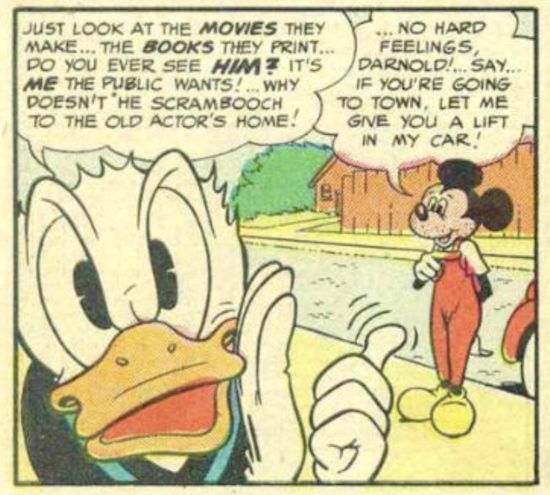

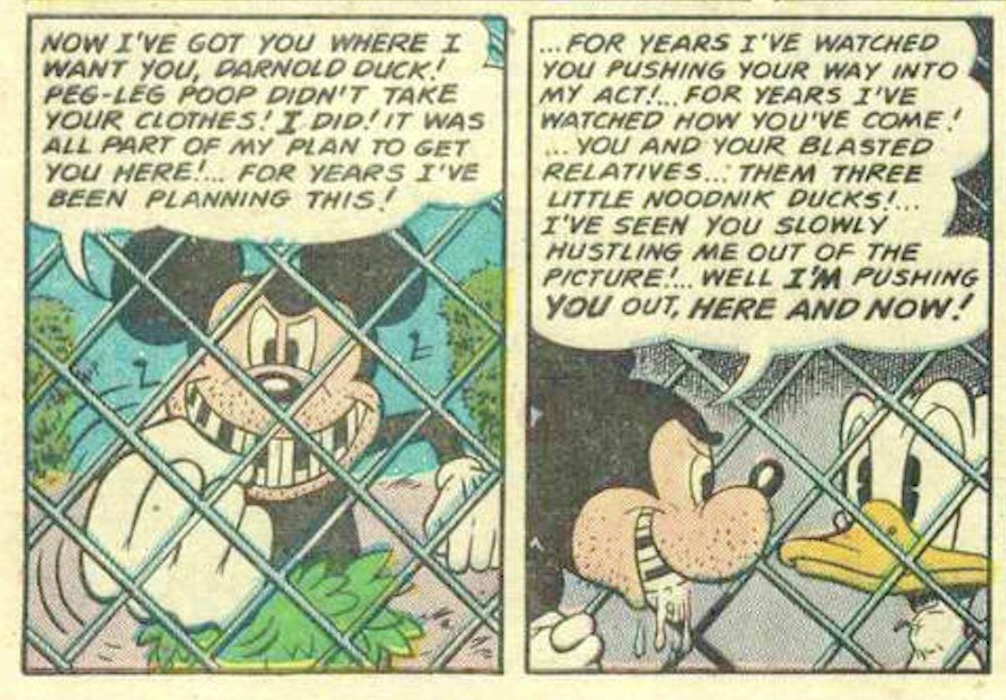

Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman’s 1955 “Mickey Rodent!” strip, which appeared in Mad #19, portrays “Mickey Rodent” as an unshaven, washed-up movie star. Although he seems his usual chipper, friendly self — we discover that Mickey deeply resents “Darnold Duck” for having stolen his limelight.

Elder (born 1921) and Kurtzman (born 1924) were born on either side of the divide between the New Gods (1914–1923) Postmodernist (1924–1933) generations. (MAD‘s William Gaines, John Severin, Dave Berg, Al Jaffee were New Gods; Wally Wood, Jack Davis, and Don Martin were Postmodernists.) They’d grown up with Mickey Mouse; they’d witnessed his (d)evolution.

As noted in the Donald Steals the Show installment of this series, Elder and Kurtzman’s comic is funny… because it’s true. Beginning c. 1934, Donald Duck had eclipsed Mickey Mouse in popularity because — unlike Mickey, who’d become an increasingly bland role model for kids, and Disney’s corporate mascot — Donald remained irascible, lazy, pranksterish. So when Darnold Duck says, in an aside to the reader, “Just look at the movies they make… the books they print… do you ever see him? It’s me the public wants!”, he’s telling it like it is. We get the sense that Elder and Kurtzman aren’t just poking fun at Mickey Mouse; they’re also rooting for him to return to form, to stop being so lame.

PS: At the time of this MAD comic, Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories was the best-selling comic book in the United States. The most popular issues featured Carl Barks’ 10-page stories about Donald Duck and his nephews, Huey, Dewey and Louie — not to mention Uncle Scrooge and the Beagle Boys. I’ve elsewhere described Barks’s DD stories as being among the greatest adventure stories of the 20th century.

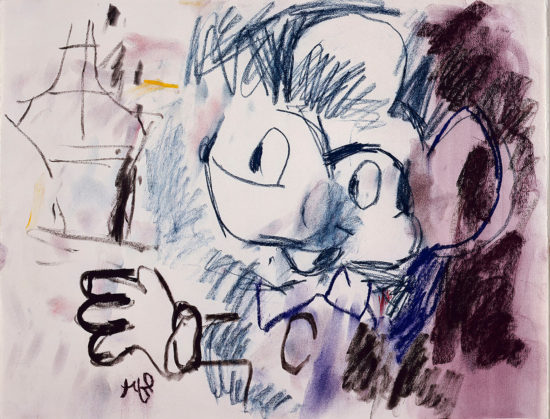

Roy Lichtenstein (born 1923) also grew up with Mickey; like Elder and Kurtzman, he no doubt felt disappointed and disgusted as he watched MM evolve into an insipid corporate mascot. Circa 1957, he began painting in the style of Abstract Expressionism — though he couldn’t help but subvert the genre’s austere strictures by incorporating hidden images of Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Bugs Bunny into his paintings. (These canvases were destroyed when the artist used them as floor mats.) Below: A preliminary Lichtenstein drawing, “Mickey Mouse I” (1958).

In 1960, Lichtenstein’s friend and Rutgers colleague, the avant-garde artist Allan Kaprow, who coined the phrase “happening,” introduced him to Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. These artists’ interest in appropriating/recuperating pop culture imagery proved inspiring. In 1961, prompted by his children’s complaint that he couldn’t draw well, Lichtenstein painted his first full-scale Pop Art picture. He scaled up a scene of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck out fishing (inspired by a scene from a 1960 children’s book, Donald Duck: Lost and Found); he included a speech bubble and laboriously stenciled Ben-Day dots, which were in those days used to produce inexpensive comic books and magazines.

Look Mickey is considered Lichtenstein’s most formative work. Bright, eye-popping and entertaining — but also deadpan, playfully subversive — the painting signaled Lichtenstein’s break from Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on brushstroke, gesture, and the artist’s mark. Along with Warhol and Oldenburg, Lichtenstein found himself in the vanguard of the Pop Art movement. The painting somehow pokes fun at dumb, insipid MM while at the same time emulating the early MM’s pranksterism. Like the subject of Look Mickey, Lichtenstein would spend the rest of his career laughing up his sleeve at artists with delusions of grandeur.

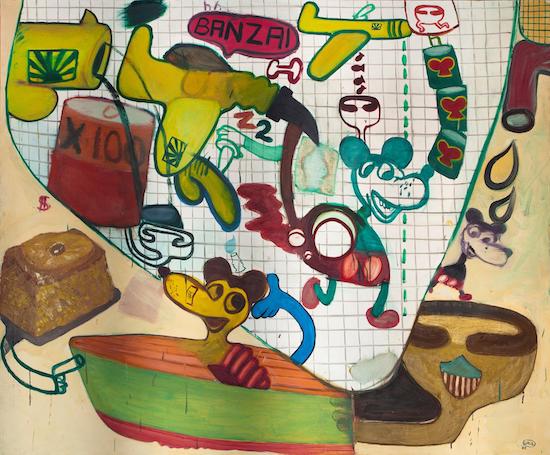

During the Fifties, Peter Saul (born 1934) developed his own unique, Pop Art-adjacent idiom. Influenced by MAD Magazine and Plastic Man, his genre-defying paintings satirized American culture and deliberately set out to offend good taste. During the Sixties, Saul would become well-known for his stream-of-consciousness, subjective interpretations of the Vietnam War, as well as ferocious psychological portraits of politicians and other personalities, in a tight linear style using Dayglo colors. I find it really instructive to look at his earlier work, which feels so contemporary…

Saul’s childish-looking 1962 painting Mickey Mouse vs. the Japs (the title of which suggests a parody of wartime Disney cartoons), above, appears — to this viewer — to poke fun not merely at Mickey Mouse, but at Pop Art’s appropriation of MM too. Saul demonstrates here a nobrow approach that’s a decade or two ahead of its time.

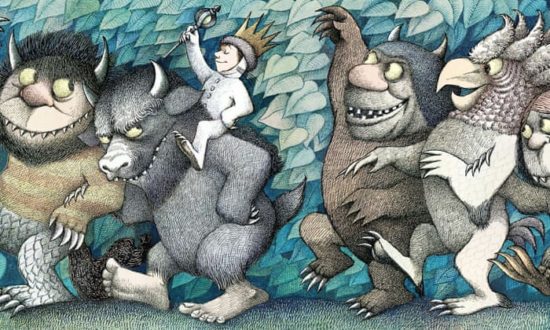

Maurice Sendak‘s masterwork, Where the Wild Things Are, was published in 1963. Max — who wears an animal costume to bed — reminds us of Sendak himself, who as a child had a special affinity for Mickey Mouse, even wearing white gloves to look more like MM.

In a 2005 NPR interview, Sendak (born in 1928 the same year as MM) would recall:

I fell in love Mickey, because I went to the movies almost every day with my sister and brother, and you had a double feature and a cartoon in the middle, so you were there for hours out of the hands of your parents. And there’s the cartoon, and when I saw that cartoon, I went into a frenzy. I remember my sister saying, ‘We knew it was coming, and Jackie would grab you by one arm and I would grab you by the other arm and you would have a seizure.’ First the big head would appear with radiant lights coming out of it. Remember that? And I adored him and I still do. I adore him from then. I don’t adore him now because he’s a fat whore, you know? He —Disney sold him into slavery, and he’s nothing. He’s nothing.

Like other artists mentioned in this post, Sendak loved the early Mickey (he’d amass one of the world’s finest collections of early Mickey memorabilia), and despised the later Mickey. In a 1978 essay commissioned for MM’s 50th birthday, Sendak would lament the change in how MM was drawn, which transformed the character “from a common street mouse to whom kids growing up in the Depression could relate, into a wide-eyed, commercialized character more palatable to a mainstream audience.”

In the same essay, Sendak would describe what he’d had to go through in order to be able to love MM despite what he’d become:

In [art] school, I learned to despise Walt Disney. I was told that he corrupted the fairy tale and that he was the personification of poor taste. I began to suspect my own instinctual response to Mickey. It took me nearly 20 years to rediscover the pleasure of that first response and to fuse it with my own work as an artist. It took me just as long to forget the corrupting effect of school.

Where the Wild Things Are, not to mention In the Night Kitchen (starring an elastic, pranksterish, gung-ho boy named Mickey) is the result of this fusion — of Sendak’s child-like, innocent worship of MM, and his cynical, sophisticated adult take.

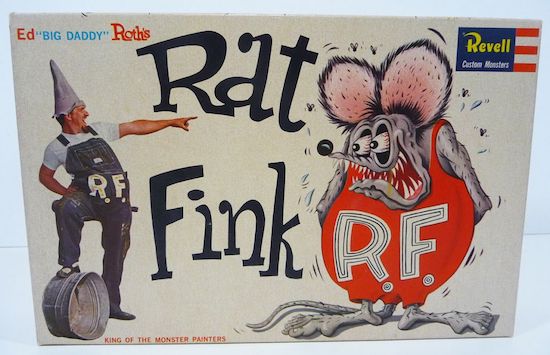

We’ll conclude our survey of the Fifties MM backlash with a brief consideration of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s hot-rod mascot Rat Fink.

Roth, an artist, cartoonist, and custom car designer and builder, became a key figure in Southern California’s Kustom Kulture and hot rod movement during the Fifties. Born a bit later (1932) than the other figures we’ve discussed in this post, he likely was less familiar with the early — witty, anarchic, elastic — MM than they were. Instead, he would have grown up with the cheerful, gung-ho, pro-American, increasingy insipid Mickey… which perhaps explains why his parody is comparatively more savage. He lacks any love for MM.

A grotesque, slavering, mutated rodent with MM’s round ears, crazed eyes and sharp teeth, Rat Fink was originally intended to promote Roth’s custom car kits and art brand. However, after the anti-Mickey character first appeared in a Car Craft magazine ad in 1963, Rat Fink went viral. The Revell Model Company quickly issued a perennially popular plastic model kit of the character.

Big Daddy lived near Disneyland, and was thoroughly sick of seeing the Disney Company’s mascot on t-shirts, wallets, keychains, stickers, and toys. Throughout the Sixties (1964–1973), he’d get his revenge by selling innumerable Rat Fink shirts, wallets, keychains, stickers, and toys. RF remains a beloved emblem of weirdo culture.