One of 10 items cross-posted from SEMIONAUT.

When Raymond Williams suggested, during a 1981 lecture, that semiotics is a science of signs and systems “not confined to language,” he was referring to post-structuralist efforts by Barthes and others to “read” certain phenomena, e.g. fashion or pro wrestling, as though they were language-like systems of signs — albeit ones where (unlike language) the system itself is never and can never be disclosed. Williams described this sort of semiotic enterprise as “radical” and “explosive.”

In The Whole Creature, her 2006 book about complexity science and biosemiotics, Wendy Wheeler goes further. She proposes that Williams was also

surely thinking of the usefulness of systems of ‘reading’ which do not reduce knowing to knowing in conceptual linguistic terms, but in which we can talk, for example, of ‘reading’ the combination of gesture, rhythm, tone and space in a dance, or of colour, brushstroke and content in a painting. He was concerned, as others have been before and after him, with those kinds of knowledges which are embodied in lived and skilful engagement with the world and with other embodied creatures.

Williams’ lecture, as far as I can tell, does not say any of this! However, Wheeler’s exegesis of the “Creative Mind” chapter of his The Long Revolution (1961) persuades me that Williams may indeed have been thinking along those lines. Really, I don’t care whether or not Wheeler’s supposition is correct. I’m fascinated by her articulation of a radical/explosive form of knowledge that cannot be “read” and conveyed (not wholly, anyway) in conceptual/propositional language, but which instead must be “read” and conveyed semiotically.

“Tacit knowing,” to use Michael Polanyi’s terminology, or “tacit, semiotic knowledge,” to use Wheeler’s, means learning to “read” an unwritten language, or decode a system of signs that was never encoded to begin with. When you put it that way, semiotic knowing sounds eerily similar to “patternicity” or apophenia — i.e., seeing meaningful patterns or connections in random (meaningless) data. Which is something that paranoiacs do. Yet as Polanyi and others have sought to demonstrate, semiotic knowing is an activity in which every single human engages, e.g., when we learn how to ride a bicycle, or when we become pro wrestlers or fashion designers. It’s an activity that a select few people do brilliantly — and we call such people not paranoiacs, but geniuses! That said, we don’t necessarily treat these geniuses with much compassion.

When Wheeler notes that “others have been [concerned with semiotic knowing] before” Williams was, to whom does she refer? She points to Husserl, and elsewhere mentions the German and English Romantics. She’s not incorrect — however, in order to locate pre-Williams examples of men and women who demonstrate abnormal expertise in semiotic knowing (let’s call such men and women semionauts), there’s no need to ascend into such lofty realms of culture.

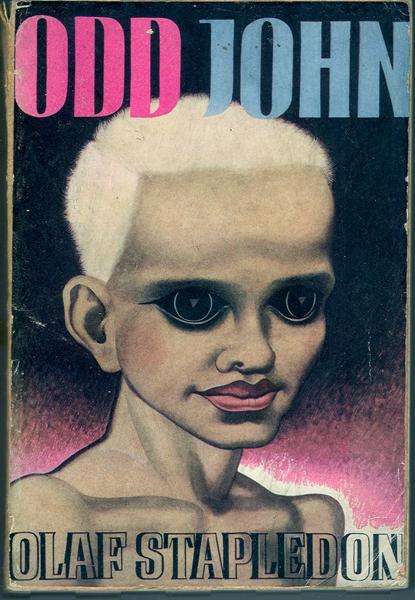

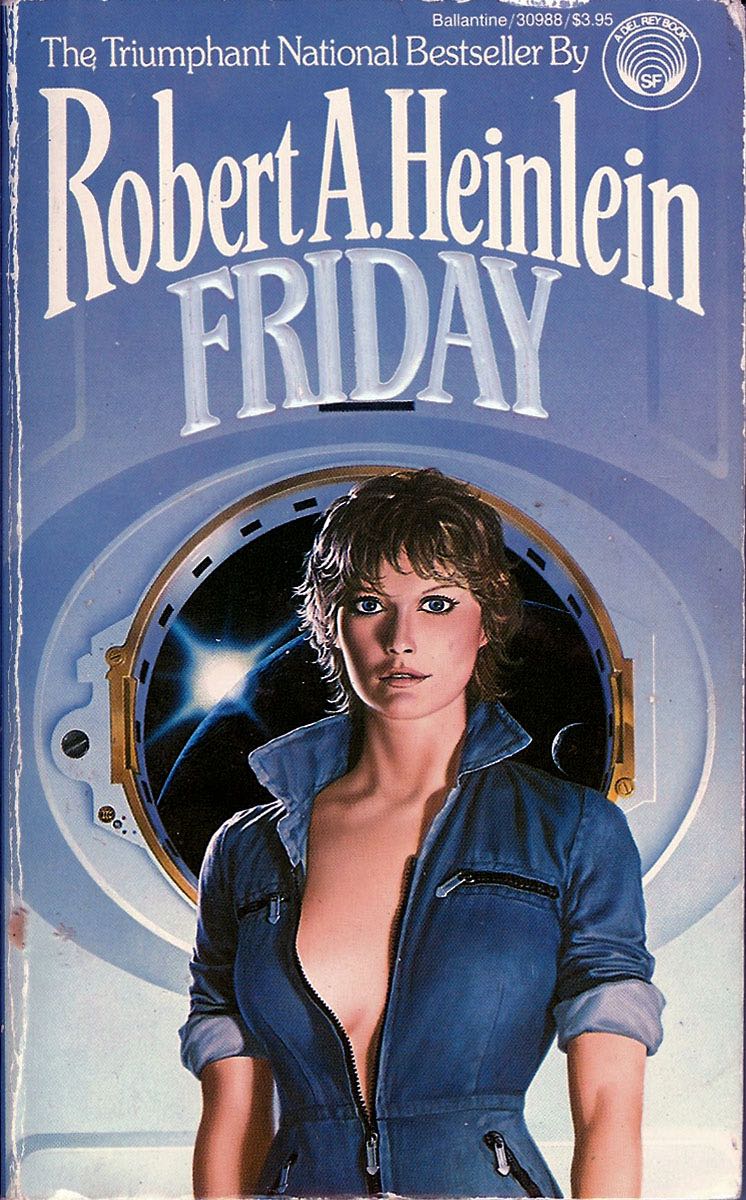

From the titular protagonist of J.D. Beresford’s novel The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911) to the titular protagonist of Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John (1935), to the titular protagonist of Robert Heinlein’s Friday (1982, but presumably written before Williams’ 1981 speech), science fiction is replete with fictional semionauts. NB: Adrian Veidt (aka Ozymandias), the multiple-TV-watching genius in Alan Moore’s Watchmen is a post-Williams fictional semionaut; Moore’s graphic novel was serialized in 1986-87.

The pathos of the semionaut, as depicted in science fiction (and in other genres of pulp fiction; Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, for example), is that although she (Heinlein’s Friday, among others, is female) can draw expertly and productively upon experiential, phenomenological knowledge — “the not wholly self-present or self-conscious knowledge of a body in the company of a self-reflexive mind capable of nurturing it,” as Wheeler puts it — she finds herself (alas) surrounded by normal humans who demand that she translate her insights into conceptual and propositional language. As a result, she can seem inarticulate, stupid, because her less talented contemporaries cannot communicate semiotically — i.e., verbally and nonverbally.

Worse, because semiotic knowing “hovers somewhere between the experiential [and “disattentive”] cunning of the animal and the more self-disciplined and attentive cunning of the man” (Wheeler, again), the sci-fi semionaut may seem only half-human, to those around her. While still a child, Stapledon’s Odd John is described as “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage … half monkey, half gargogyle, yet wholly urchin.” David Bowie was surely thinking [to use a Wheelerism] of Odd John when he wrote 1971’s “Oh! You Pretty Things.”

Pity the poor semionaut! Or don’t: after all, Bowie’s song claims that we “gotta make way for the homo superior.”

Original publication date: November 2010.