“I’m the Mouse”

Keith Haring, Mickey Mouse (1981)

In the previous installment of this series, we reviewed a variety of Sixties-era (1964–1973) responses to Mickey Mouse that were, for the most part, petulant and snarky. However, during the Sixties and Seventies (1974–1983) there were a handful of artists who engaged with MM in ways that were deeper, weirder, more emotional than that. Accordingly, these artists’ output remains fascinating today. Rather than being of merely historical interest, the works on display in this post invite viewers to enter a rich, imaginative Mickey-scape.

Claes Oldenburg (born 1929) made his name as a Pop Art artist, known for his Fifties- (1954–1963) and Sixties-era humorous sculptures of everyday items and consumer goods, as well as for his Sixties-era “happenings.” In 1968 — that is to say, at the apex of the Sixties — he began to use the figure of a “Geometric Mouse” in his work.

“It comes in many sizes, all the same form. It’s a kind of antidote to Mickey Mouse,” Oldenburg would later explain, of his work. “Mickey Mouse is soft and cuddly and all curves. Whereas the ‘Geometric Mouse’ doesn’t have any curves. … It’s intended to be a symbol more of mental action than Mickey Mouse, which is more about fun.” Like Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, Oldenburg was fascinated with MM-as-icon, but disappointed with what MM had come to represent — i.e., “soft and cuddly” inoffensive cuteness, and sentimental “fun.” Whereas Roth’s Rat Fink was designed to repel straights and attract freaks and weirdos, Oldenburg’s Geometric Mouse was designed to provoke viewers and disrupt their expectations in a thoughtful way.

Oldenburg’s squared-off version of Mickey Mouse’s head would prove at least as ubiquitous as Roth’s Rat Fink. Throughout the rest of the Sixties and for half century since then, it has appeared in street banners, proposals for museum façades, and even mouse-shaped museum installed in 2013 at MoMA.

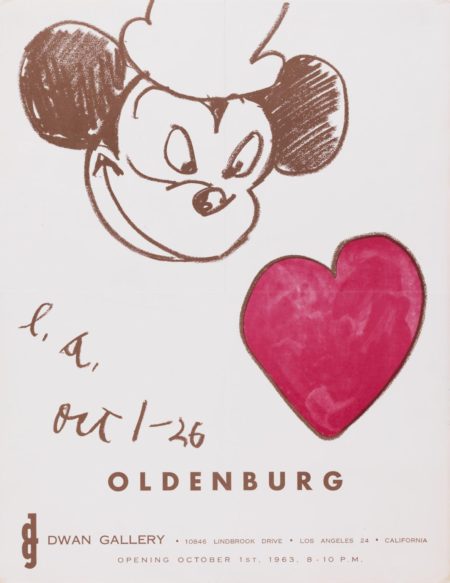

The Geometric Mouse is not a heavy-handed parody of Mickey Mouse; instead, it’s a kind of broken-hearted love letter to Disney. In fact, the first appearance of the MM motif in Oldenburg’s came in 1963 (the same year that Rat Fink first appered), in the form of a poster — shown below — in which a fiendish-looking Mickey Mouse leers at a red heart.

The Geometric Mouse motif was inspired by the artist’s 1968 visit to LA’s Disney Studios. “I’m the Mouse,” Oldenburg once said; that is to say, he’s not merely parodying meaningless iconography. Instead, he’s offering an improvement on Disney’s MM: a version of Mickey that startles us into thinking for ourselves, rather than lulling us into a state of consumerist complacency. The rage or despair felt by those who identify with the early Mickey doesn’t have to result in childish, knee-jerk parodies. Instead, in a Hegelian move, it is possible to abolish-preserve-and-transcend Mickey Mouse.

Garry Apgar, author of the very useful but frequently wrong-headed 2015 book Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit , claims that Oldenburg and others “understand how important Disney is as a cultural phenomenon but just don’t like him, or can’t admit that they like him or embrace what he accomplished.” It’s more complex than that, as I’ve tried to articulate above. Small wonder, then, that Oldenburg refused to allow Apgar to include photos of the “Geometric Mouse” sculptures in his book.

I haven’t seen avant-garde moviemaker Ken Jacobs’s (born 1933) silent film “Lisa and Joey in Connecticut” (from 1965), but I understand that it intercuts a vintage Mickey Mouse cartoon with shots of young mother, father and their little boy in a way that is touching without being sentimental or cloying; I’m intrigued.

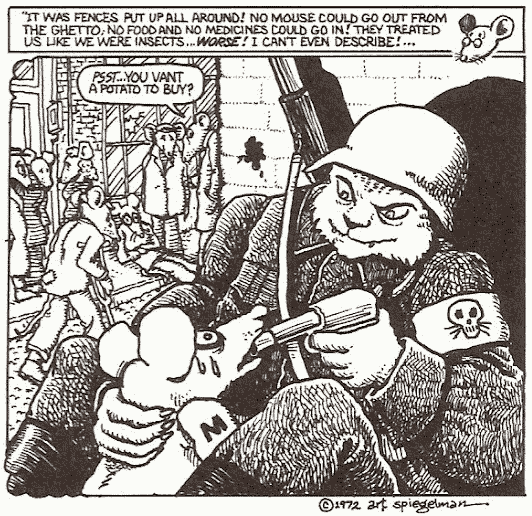

At the tail end of the Sixties — in 1972, to be precise — underground cartoonist Art Spiegelman (born 1948) was sitting in on Jacobs’s film class, in a session dedicated to analyzing MM’s debt to the racist tradition of minstrelsy (as noted in the first installment in this series). Jacobs “was showing Mickey Mouse’s Steamboat Willie, when he’s still a Jazz Age character rather than kind of a square, and then pointed out that Mickey Mouse is just Al Jolson with funny round ears on top, that it was kind of all a form of minstrelsy,” Spiegelman would recount. “And then I thought I really had the answer to the question, which was just, ‘All right, I’ll do [a comic] about racism in America with Ku Klux cats and mice.’” Hic incipit Spiegelman’s Maus, an early version of which first appeared that same year (see above).

Maus, in the form that was serialized from 1980 to 1991, depicts Spiegelman interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. The work employs postmodernist techniques and represents Jews as mice, Germans as cats, and Poles as pigs. It was the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize.

The Romanian-born Saul Steinberg (b. 1914), who in 1941 was forced to flee the country due to the anti-Semitic racial laws promulgated by Romania’s Fascist government, published his first drawing in The New Yorker that same year. The Saul Steinberg Foundation’s website describes him as “a modernist without portfolio, constantly crossing boundaries into uncharted visual territory. In subject matter and styles, he made no distinction between high and low art, which he freely conflated in an oeuvre that is stylistically diverse yet consistent in depth and visual imagination.” He’s one of my favorite artists, and his use of MM as a motif is extraordinary.

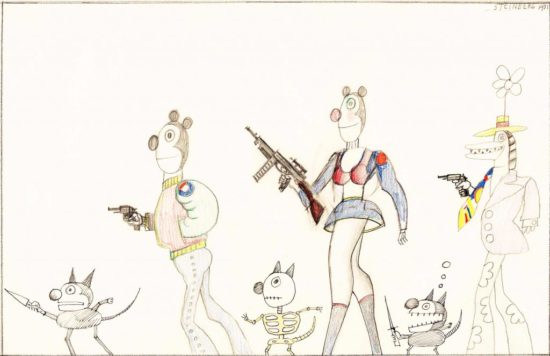

During the Sixties, in order to express his aversion to the Vietnam War, the American political culture that led the country into it, not to mention aspects of American youth culture, Steinberg apropriated the far-out, trippy style of underground comix. His New Yorker drawings from this period feature out-of-control cops, predatory humans and animals, not to mention thugs and terrorists… many of whom appear to be twisted versions of MM.

Steinberg found Mickey Mouse “really frightening,” he claimed. He certainly drew many frightening MM-esque characters. Yet at the same time, like other artists mentioned in this post, he also seems to have identified with MM.

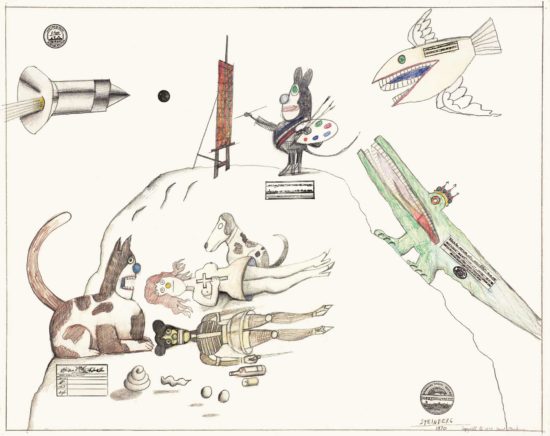

In the iconography of Steinberg’s 1970 drawing “Artist” (above), the titular artist is a Mickey Mouse figure threatened by a fish, a crocodile, a cat, and a rocket. A Minnie Mouse figure, grasping a switchblade, seems to have perished nearby.

Steinberg’s urban characters — smoking, toting weapons, wearing obnoxious outfits, and engaged in acts of violence and debauchery, anticipate the 1992–on comic strip Underworld, by Kaz. More on Kaz later.

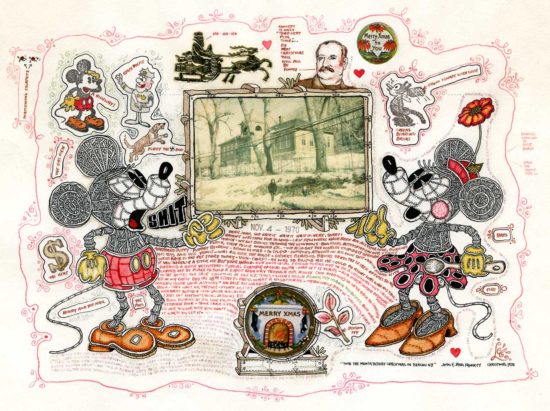

John Fawcett, a longtime art teacher at the University of Connecticut, who also contributed to Mike Barrier’s underground comic Funny World, was an obsessive collector of MM memorabilia. However, “I’m not interested in nostalgia,” he insisted. “I’m interested in aesthetics.” His drawings and paintings deployed MM as a a symbol — one of the most potent symbols of the 20th century: “My work is about color interaction and artistic process; it’s not about a mouse that is the symbol of a theme park in Florida.” Along with Ernest Trova’s MM pieces, Fawcett’s work straddles the line between fan art and something deeply personal.

Moose Mouse, an intricate giant mechanical MM-shaped mouse, is the central character in much of Fawcett’s work. His 1970 comic Works of Art Comics, Starring Moose Mouse is something I’d love to see. (Summer 2020 update: Thanks, Rick Pinchera, for letting me borrow your copy of Works of Art Comics, Starring Moose Mouse — it does not disappoint!)

See 1970 image of Fawcett with his MM toy collection here. And here’s a collection of Fawcett’s MM art.

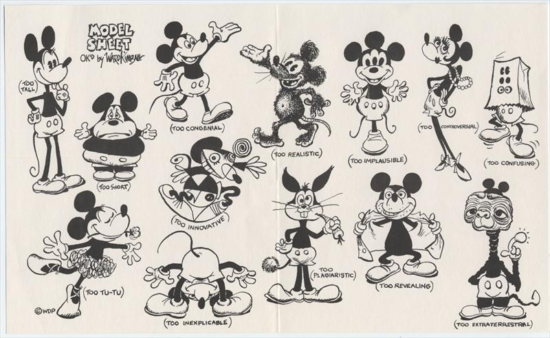

Ward Kimball (born 1914) is best known as one of Disney’s Nine Old Men of animators; he’s also an Oscar-winning director, and multitalented artist. Having joined Disney in 1934, and after working on many Silly Symphonies and Mickey Mouse shorts, he graduated to working on feature-length efforts. For example, he designed and oversaw the animation of Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio, the crows in Dumbo, and half of the characters in Alice in Wonderland.

After retiring from Disney in 1973, Kimball was freed up to produce humorous sketches of MM — which, during the 1974–1983 era, he seems to have done a few times. These aren’t snarky parodies: As with the high-lowbrow works showcased in this post by the likes of Oldenburg, Steinberg, Ungerer, Haring, and Basquiat, MM is important to Kimball. Although his 1976 sketch of “Mangle Mouse (an Acid Freak)” may remind us of the snarky parodies we saw in this series’ previous post, the rest of Kimball’s MM sketches reveal that — in a goofy, light-hearted way — Kimball was interested in revivifying Mickey, turning him back into a witty trickster figure.

All of which is to say, I read Kimball’s MM sketches as an example of what the Romans called aemulatio — showing respect for one’s predecessors by delivering an improved version of their work.

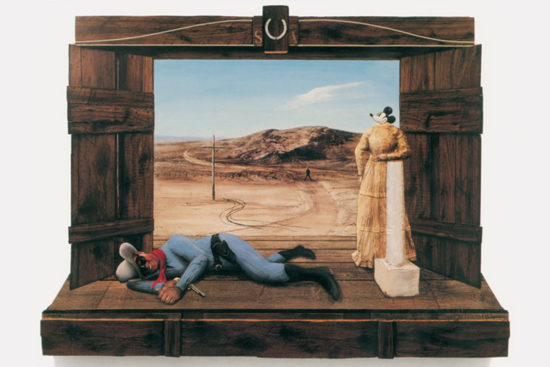

Fun fact: Ward Kimball’s son-in-law, artist Llyn Foulkes (born 1934), began using MM in his work at the very end of the 1974–1983 era. Above, for example, is The Last Outpost (1983), an assemblage in which the Lone Ranger lies dying — while a frontierswoman with a smiling MM head looks on mischievously. (Also take a look at Foulkes’s 2006 piece Mr. President, among others.)

Foulkes’s motivation for using MM, in a sinister way, in his works — “Walt Disney was a right-wing Republican and an anti-communist who named names,” he’s said in an interview; “Mickey Mouse represents America, and the good, happy, friendly, passion side of America as opposed to a mean, evil American flag[,] which is really crazy because if you really think about it, everybody’s got this backwards,” he’s said in another interview — might make him sound like a Sixties throwback. However, his work has no obvious, ham-fisted message; it’s both political and personal.

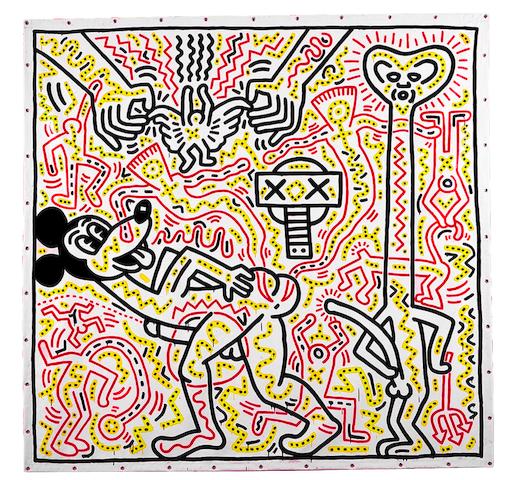

Last year, the image shown above — Keith Haring’s (born 1958) Untitled (1983) — sold for over $4 million. Here’s an excerpt from the Bonhams catalog describing this painting:

Untitled is quintessentially Haring, whilst also being a work from a singular time in New York. Arguably one of Haring’s most complex works compositionally, it also carries a strong message. The work explodes with color, buzzing with fluorescent pink and pops of yellow. Theoretically simple in execution and only employing three colors, the work remains deeply dynamic — pulling the eye across its highly worked surface. Haring’s signature figures, characters with whom we have all become deeply familiar with [sic] in the cultural zeitgeist, can be found throughout the work: an angel, a dog and dancing figures all move, dance and jump throughout it. It also seems however to be a warning about the complications of unprotected sex. Mickey Mouse, a subject of fascination for Haring who appears throughout his oeuvre, is seen contemplating sex with a second figure, perhaps the devil. A figure wearing a gas mask, which can also be interpreted as a screw — an example of Haring’s strong ability to create double entendre — is placed between the figures of a devil and angel. The angel signaling not just an alternative to the devil — seen at the lower right-hand side of the composition with the trident, symbolically used throughout art history when depicting a demon — but also even alluding to death that might befall him from this choice.

Haring’s father, Allen, was an amateur cartoonist; as a child Keith particularly liked drawing Mickey Mouse. Haring would deploy MM not infrequently — “as a naïve, child-like figure in his works, using him to instill joy and innocence in paintings which simultaneously capture the grit and darkness of the 1980s.”

In a 1981 interview, Haring would explain that he drew MM “partly because I could draw it so well and partly because it’s a loaded image. It’s ultimately a symbol of America more than anything else.”

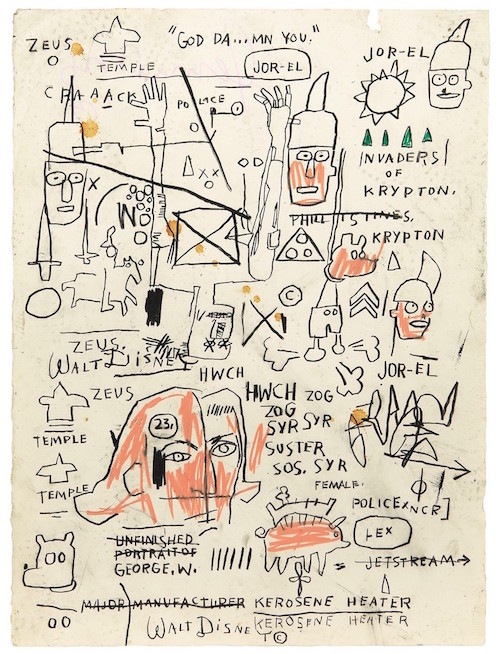

One more painting: In addition to the head of George Washington and references to Superman, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s (born 1960) 1983 drawing Untitled (Walt Disney) features an armless Mickey Mouse hanging from a noose.