Code-X (Intro)

The following is a post that I wrote in 2014, when kicking off the CODE-X series at HILOBROW. By June 2016, we’d reached 100 posts in the series, and we stopped. Here at SEMIOVOX, we’ve recently begun reposting installments from the original CODE-X series; and adding new installments, as well.

Reality, according to the post-structuralists whom members of my generation were encouraged to take seriously in the Eighties, is a shapeless mass of experience (call it: nature) upon which is superimposed — pre-consciously, and therefore ultra-persuasively — a complex, language-like matrix of… not meaning, exactly, because there is no such thing, but meaningfulness (call it: culture). These theorists (Derrida, Baudrillard, Kristeva, Deleuze and Guattari, the later Foucault and later Barthes) suggested that a meditative attention to this matrix’s gaps and glitches might reveal glimpses of natura naturans, reality in its never-ending state of flux and mutation. Far out!

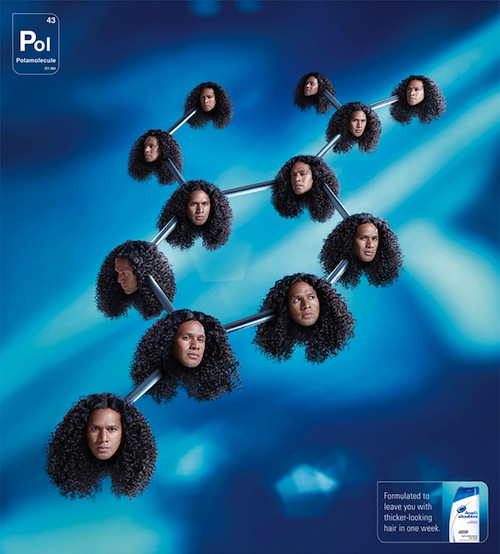

The aim of the forthcoming CODE-X series is more modest, less mystical and liberatory than the post-structuralists’ mission. Via detailed observational analysis, this series aims to surface not nature, but culture. Each post in this series will identify one code: a single node in the vast meaningfulness-matrix structuring our perception of the everyday world.

The Code-X series will be a minor contribution, a footnote, to the codex begun and abandoned by the post-structuralists’ predecessors. Once upon a time, structuralist linguists, anthropologists, psychologists, historians, and social critics including Saussure, Lévi-Strauss, Greimas, Lacan, Althusser, the early Foucault (of Madness and Civilization, The Birth of the Clinic, The Order of Things, The Archaeology of Knowledge), and the early Barthes (of Elements of Semiology, Mythologies, The Fashion System) sought to analyze not merely what everyday objects, actions, and gestures within a given social order mean… but how they mean. How does the a priori network of classifications, categories, and concepts (a.k.a. the all-encompassing sign-field) through which each of us intuitively reads and interprets everyday life function? What are the implicit assumptions (or “mythologies”) we’ve absorbed without consciously evaluating them?

Since the late 1990s, I’ve worked as a semiotic culture and brand analyst. My agency, SEMIOVOX, audits the codes of product categories and cultural territories from the outside-in, i.e., we attempt to operate as alien anthropologists who regard the apparently permanent, natural, and inevitable norms and forms of everyday life in 21st-century America as impermanent, unnatural, and evitable. At the same time, we’re acting as insiders — drawing on years of attention to cultural trends, shifts, and minutiae within our own cultures.

The sociologist Robert Friedrichs, with whom I studied as an undergrad, claimed that a social scientist should be a “minotaur”: productively divided, striving to be simultaneously objective and subjective. [“An attitude at once critical [objective] and apologetic [subjective] toward the same situation is no intrinsic contradiction in terms (however often it may in fact turn out to be an empirical one) but a sign of a certain level of intellectual sophistication.” — Clifford Geertz.] Operating as a minotaur semiotician, on behalf of the many brands, agencies, and institutions who’ve hired me, I’ve haphazardly worked towards what Barthes optimistically called a “total ideological description” of the implicit norms and forms communicated via pop culture, advertising, and packaging. Ideology, that is, not in the Marxist sense of an explicit idea fed by the bourgeoisie to the masses, but in the Althusserian sense of an implicit, unquestionable “primary ‘obviousness.’”

Alas! The CODE-X series is doomed to failure. Many of the codes analyzed in the series will strike readers as banal, quotidian, obvious. Why? Because that’s exactly how semiotic [meaningfulness-producing] codes function in our daily lives; they operate at the that’s-just-how-things-are level of primary “obviousness.” Also, an all-encompassing cultural codex is (as the post-structuralists were correct to point out) an impossibility — because culture is always changing. What’s more, no isolated code means anything except inasmuch as it differs from all related codes within a category — so therefore extracting one code at a time from various cultural territories (e.g., British-ness, Happiness, Tough Mom) and product categories (e.g., Automotive, Male Grooming, Chocolate Milk) won’t do much to enlighten readers.

Despite all the arguments against this series I’ve just listed, though, let’s give it a whirl.