A version of this essay was published at HILOBROW in 2010.

Since age 12 or so, I’ve collected 20th-century paperback adventure novels whose titles include a free-standing letter “X.” It wasn’t until recently, however, when I decided to organize my collection chronologically on the bookshelf, that I realized I’d stumbled upon a meme that communicated itself, virally, from one pulp genre to another for several decades.

The following field notes — let’s call this effort “pulp-fiction meme epidemiology” — take us from the cultural era known as the Twenties (1924–1933) through the cultural era known as the Sixties (1964–1973).

Pre-Twenties

I’ve come across just two pre-1924 adventures featuring a free-standing “X”: William Hope Hodgson’s Dream of X (1912), which is an abridged version of his 1912 proto-sf novel The Night Land, and Edgar Wallace’s 1917 crime caper Kate Plus Ten, the title of which was sometimes rendered Kate Plus X. The latter doesn’t really count. So it would seem that we have Hodgson — a proto-Lovecraftian spelunker of forbidden dimensions — to thank for introducing the “X” into adventure-fiction titles. It came from beyond….

The Twenties (1924–1933)

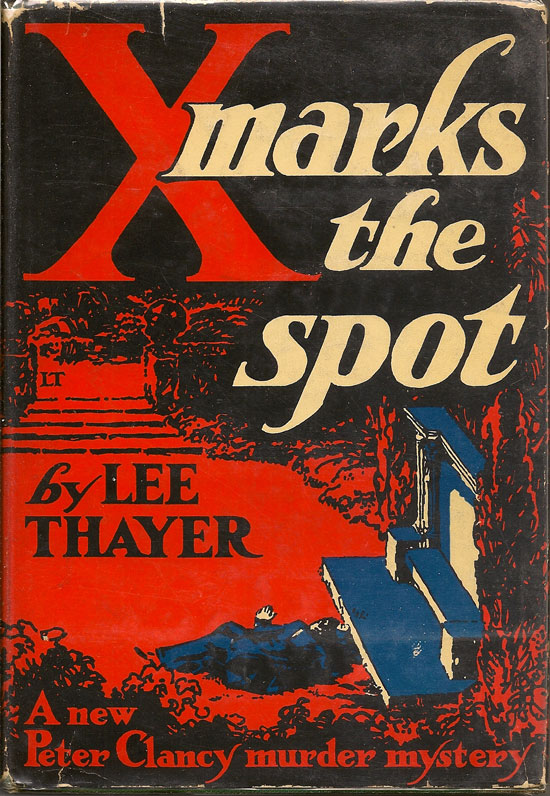

During the Twenties, the “X” found its first purchase within the crime and occult fiction genres. The title of Lee Thayer’s 1924 murder mystery X Marks the Spot winks at the idea of a marked treasure map, a trope popularized by Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 adventure Treasure Island. Fun fact: Thayer was also an artist; she specialized in book-jacket art work.

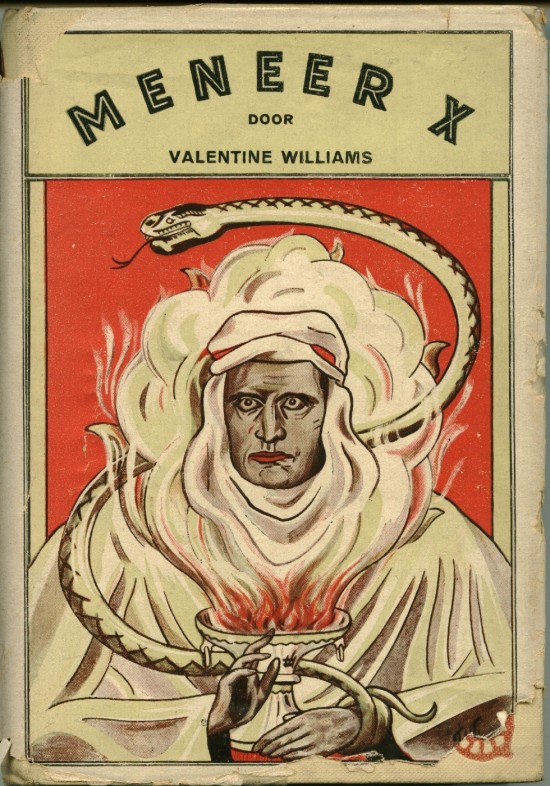

A year before he began cranking out his Simon Templar series, Leslie Charteris’s first novel was the 1927 crime adventure X Esquire. Valentine Williams’s occult adventure Meneer [Mister] X followed in 1928, and Francis Duncan’s murder mystery Dangerous Mr. X in 1929.

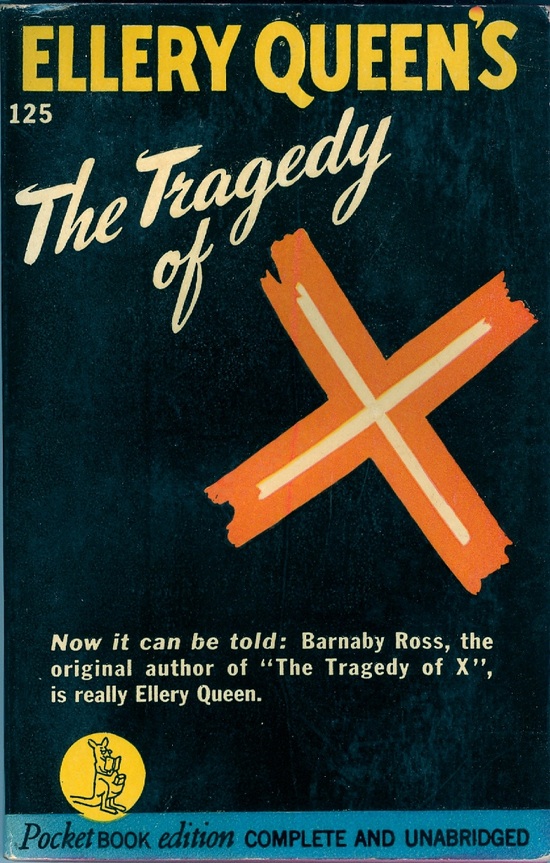

I am particularly fond of my 1941 edition of The Tragedy of X, a 1932 murder mystery by Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee, writing as Barnaby Ross (they’d later reissue it under their more famous pseudonym, Ellery Queen); I found it among my grandfather’s massive heap of WWII-era paperbacks when I was an adolescent, and it was the first “X” title I ever collected. See this post’s headline image.

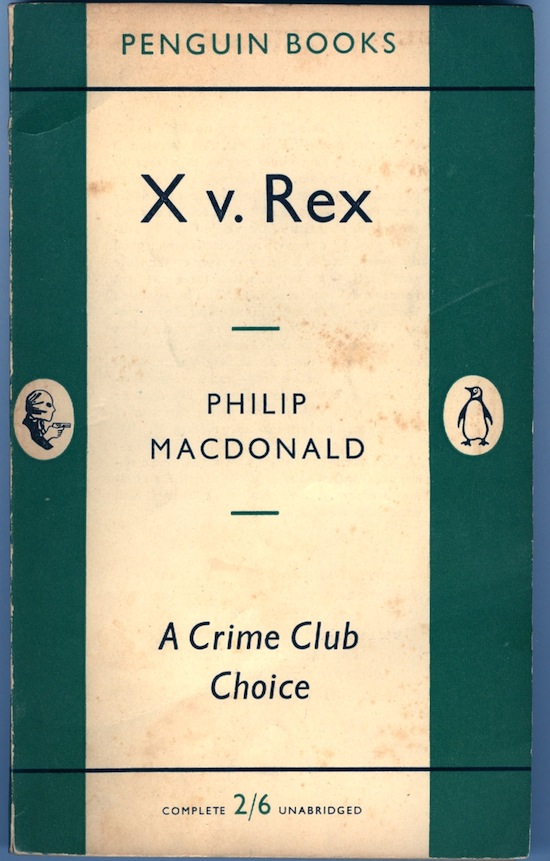

The 1933 thriller X v. Rex, an early example of the serial killer novel by Martin Porlock, was reissued the following year as The Mystery of Mr. X; Porlock was a pseudonym of Philip MacDonald, who’d later reissue the book under his own name but a different title: Mystery of the Dead Police. Fun fact: Macdonald, the grandson of Scottish novelist George MacDonald, also wrote as Oliver Fleming and Anthony Lawless.

Young Mr. X is a 1933 crime novel by Elizabeth Jordan, a remarkable woman who covered Lizzie Borden’s trial for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, edited the magazine Harper’s Bazaar, and was an active suffragist. Also in 1933, Sinclair Gluck, a British writer influenced by Edgar Wallace, published the crime novel Minus X .

Before we leave the Twenties, it’s worth mentioning the X Bar X Boys, a series of western adventures for boys created by the Stratemeyer Syndicate and written under the pseudonym of James Cody Ferris.

The Thirties (1934–1943)

The year 1936 saw the publication of Alex Kahn’s The Menace of X, Harry Stephen Keeler’s X Jones of Scotland Yard, and E.F. Bozman’s X Plus Y.

In 1937, we find Griffin Jay’s Mr. X — a not very original title, at this point. Edward Hope’s 1938 Let X Equal Marjorie, which I’ve seen described as “a gay and fairly amusing rentalette,” continues the mathematical trope. Sefton Kyle’s Miss X appeared in 1939.

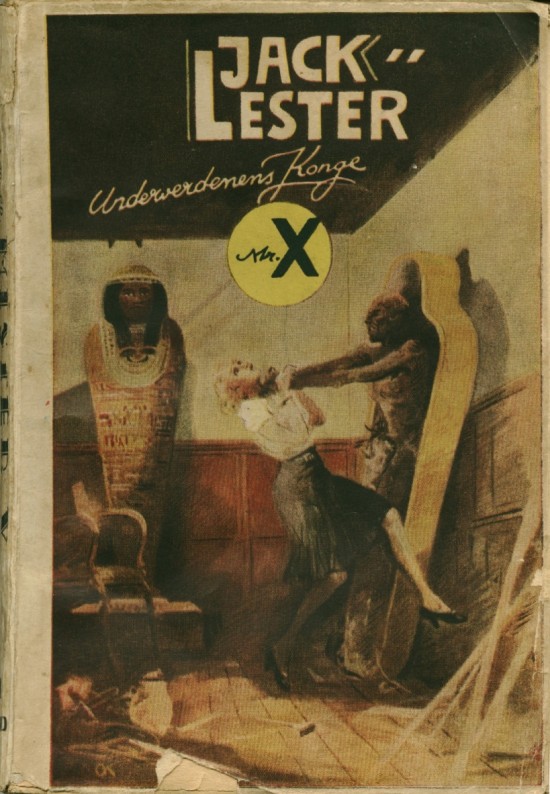

The year 194 saw the publication of a Danish novel, apparently in the supernatural horror genre, by Jack Lester; its title in translation is Mr. X: King of the Underworld. In 1943, Harry Stephen Keeler reappears with The Search for X – Y – Z, and Muriel Stafford published X Marks the Dot.

The Forties (1944–1953)

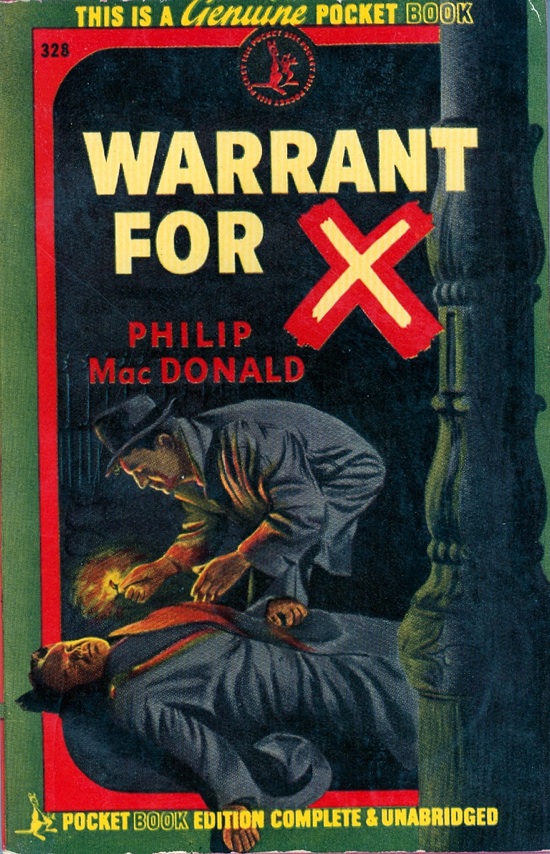

Still mostly mysteries in the Forties, though we begin to see a few science fiction novels, too. For example, Sydney Horler’s 1945 sci-fi title Virus X, the title of which I’ve borrowed for this post, is the sixth book in the Dr. Paul Vivanti series. Also, we find The Nursemaid Who Disappeared, a 1938 mystery by Philip MacDonald (author of X v. Rex, above), reissued in 1945 under the title Warrant for X.

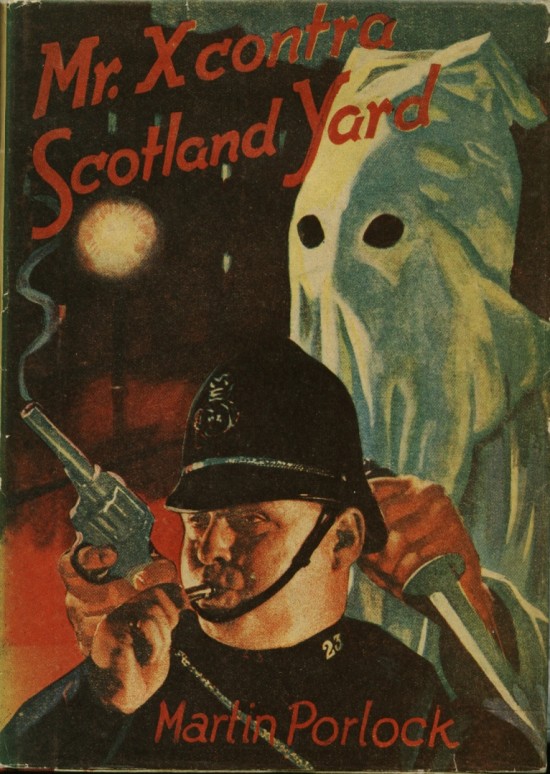

De Afschuwelijke X (c. 1946), by R. Poupon, is a Dutch/Belgian detective story. The year 1947 brings Clifford Witting’s Let X Be the Murderer, while 1948 brings Berkeley Gray’s The Spot Marked X (I can’t help but admire the dumb cleverness of this one) and Hermann Hilgendorff’s kriminalroman Professor X. Martin Porlock (Philip MacDonald) returned in 1949 with the crime thriller Mr. X contra Scotland Yard. MacDonald was a super-spreader.

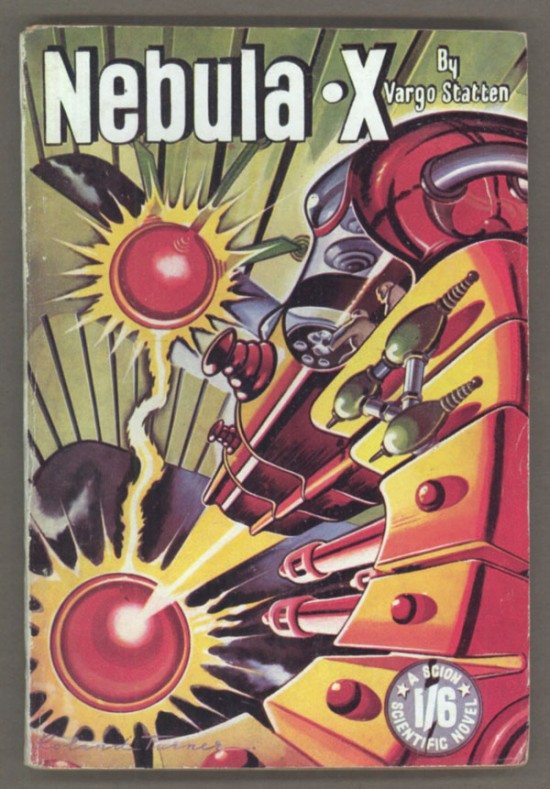

The year 1950 sees the publication of Vargo Statten’s Nebula X (“The scattered atoms of the long-dead sole survivor of a peaceful alien race annihilated by the super science of an ancient pre-antediluvian Earth civilization are reunited by Earth scientists during a laboratory experiment”), originally published in 1946 as The Multillionth Chance; and David Shaw’s Laboratory ‘X‘. “Vargo Statten” was one of several pseudonyms under which the prolific British pulp sci-fi author John Russell Fearn wrote; others included Polton Cross, Ephriam Winiki, and Astron Del Martia. Fearn would also soon publish The G-Bomb (1952; originally 1941 as The Last Secret Weapon) and Z-Formations (1953).

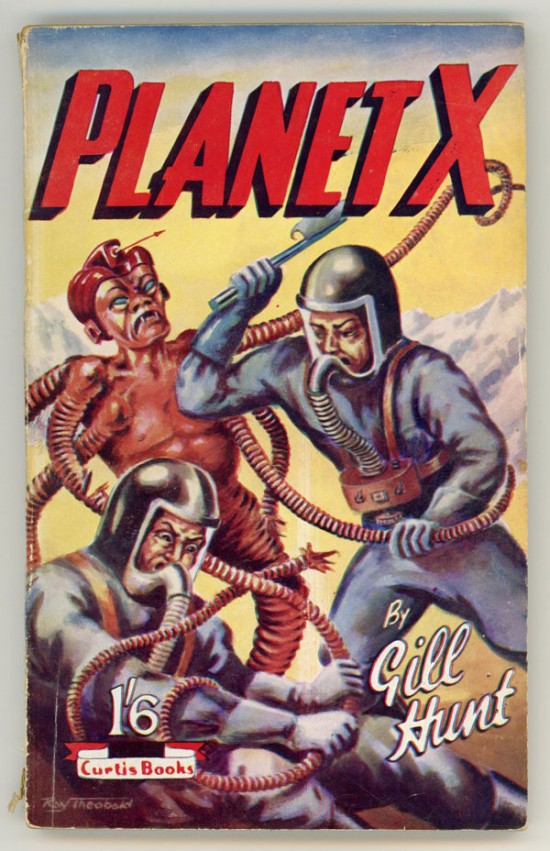

In 1951, we find Carter Brown’s Duchess Double X, and Sydney Horler returns with The Mystery of Mr. X. Also published in 1951: Jackson Budd’s The Story of Professor X and Gill Hunt’s Planet X, in which the Galactic Spacial Police Patrol pursues a space pirate to a distant planet where unpleasant, hostile alien life forms are encountered. “Space opera in the worst boys’ fiction tradition,” according to the rare book dealer L.W. Currey.

Arthur Graham’s 1952 adventure Six Against Mr. ‘X‘, which I’ve never read and don’t know anything about, is fun because there are two X’s in its title. Also published that year: Nathan Miller’s X’s Page and Mary McMullen’s The Death of Miss X (first published in 1951 as Strangle Hold).

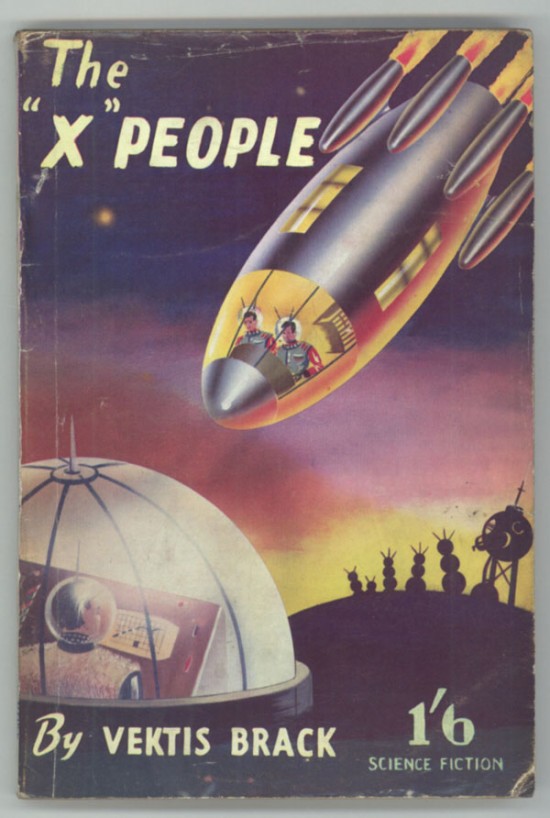

Vektis Brack’s 1953 sci-fi adventure The “X” People has a fun cover. PS: The unpersuasive name “Vektis Brack” was a house name used for three sf novels for Gannet Press (London) in the early 1950s.

The Fifties (1954–1963)

I have elsewhere suggested that the Original Generation X was born between 1954–1963. The following X titles were published during that period; except for one or two romance/mysteries, they’re all sci-fi.

Hermann Hilgendorff returns in 1954 with the Inspektor Percy Brooks kriminalroman Organisation X.

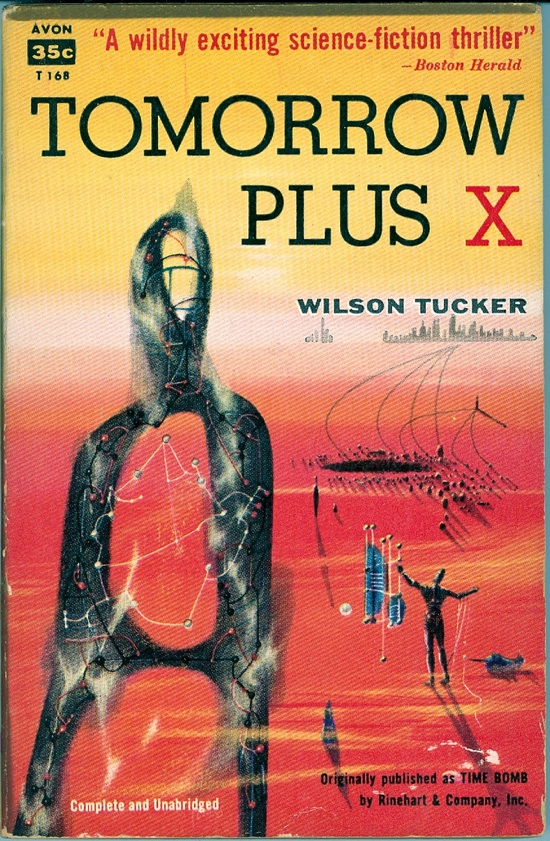

Wilson Tucker’s Time Bomb (1955), a sci-fi movel in his Gilbert Nash series, was reissued in 1957 as Tomorrow Plus X. (Also: Tucker’s 1954 collection Science Fiction Subtreasury was reissued in ’55 as Time: X.) Rene Ray’s The Strange World of Planet X came out the same year.

In 1958, we find Raymond Z. Gallun’s sci-fi adventure People Minus X, and 1959 sees the publication of Hank Searls’s The Big X. In 1960, we find Lionel Roberts’s The Face of X, Theodore Sturgeon’s sci-fi adventure Venus Plus X (nominated for a Hugo), and K. Wright’s Der rätselhafte Planet X.

Fun facts: Lionel Roberts was a pseudonym of R L(ionel) Fanthorpe, who also wrote under the excellent pen names and Karl Zeigfreid, Othello Baron, Bron Fane, Mel Jay, Marston Johns, Elton T. Neef, Peter O’Flinn, Deutero Spartacus, Trebor Thorpe, Pel Torro, Olaf Trent, and so forth. Singlehandedly responsible for several X titles, Fanthorpe is another super-spreader. Imagine if he turned out to be Philip MacDonald in disguise…

Diane Frazer’s Nurse Lily and Mister X and Evelyn Healey’s Let X Equal Murder (both 1961) are two of the few non-sf X titles from this era; Frazer’s book was the first in a long run of similar stories: e.g., Confidential Nurse (1962), Nurse Turner Runs Away (1962), An American Nurse in Paris (1963), and Nurse With a Past (1964). In 1961, we also find Tom Swift and the Visitor from Planet X by Victor Appleton II.

Fun fact: Hunter Adams was a pseudonym of Jim Lawrence, who — using the house pseudonym Victor Appleton II — wrote 24 installments in the “Tom Swift Jr.” series (including Tom Swift and the Visitor from Planet X, 1961) and the racy-sounding Tom Swift and His Megascope Space Prober, 1962); he also penned 9 Hardy Boys books under the house pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon. In the 1970s, writing as Hunter Adams, Lawrence would publish The Man from Planet X series of Peter Lance (ha ha) erotic adventures.

Karl Zeigfreid’s Zero Minus X in 1962 is another title from the multi-pseudonymed R.L. Fanthorpe. Ben Barzman’s Echo X also appeared in 1962; it is a reissue of his 1960 novel Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star. For some reason, I find copies of this one in used bookstores all the time. In 1962, we also find The X-machine, by John E. Muller — another pseudonym of R.L. Fanthorpe.

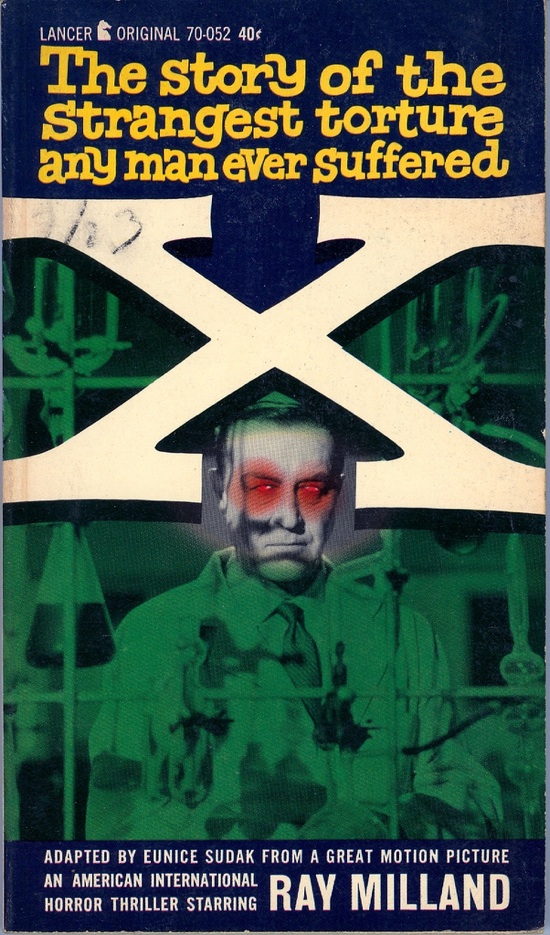

Eunice Sudak’s 1963 sci-fi thriller X is an adaptation of the 1963 movie of that title, also known as X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes. Directed on an ultra-slim budget by Roger Corman, it stars Ray Milland as Dr. James Xavier, who is driven mad by what he perceives at the center of the universe!

Also worth noting that Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s The X-Men #1 appeared in 1963. The teenage mutants’ mentor, Professor X(avier), explained in that first story that mutants “possess an extra power … one which ordinary humans do not!! That is why I call my students … X-Men, for EX-tra power.” One presumes that Professor X’s name was inspired by the movie X.

The Sixties (1964–1973)

The final flourishing of the X virus happens during this era. Although it’s mostly science fiction, we’ll also see espionage adventures in the mix.

Brian Talbot Cleeve kicks things off in 1964 with Vote “X” for Treason. There’s also a 1964 poetry collection, by James Russell Grant, titled Mister X.

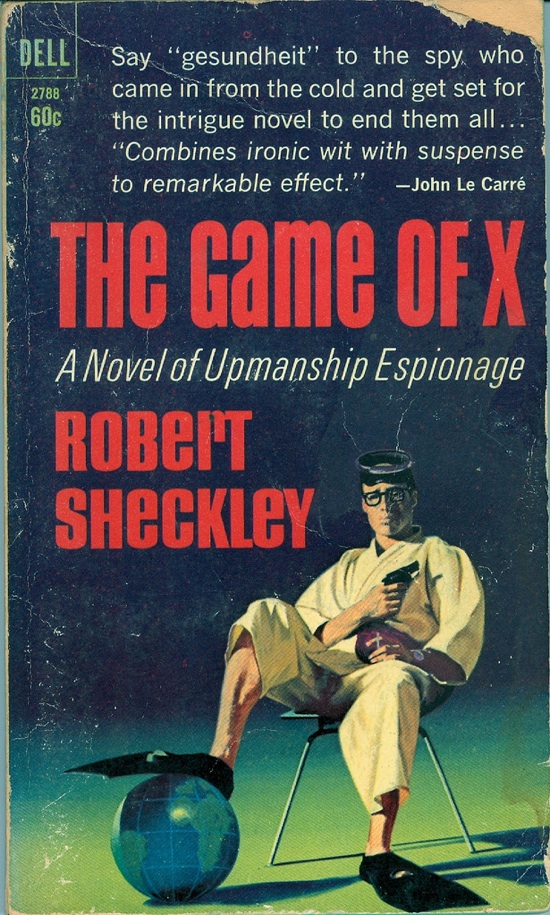

The year 1965 is an annus horribilis, in which the X virus exerts itself with one final effort before beginning to taper off. In that year alone, we find Andre Norton’s sci-fi adventure The X Factor (1965), the first installment in his Game of Stars and Comets series; John Severns’s Night in Kings X, Emile C. Schurmacher’s Assignment X: Top Secret is a wartime espionage thriller, Mack Reynolds’s Planetary Agent X (the first installment in the United Planets series), and Marsha Wayne’s Kings X Affair, among others. In 1965, we also find Force 97X, by Pel Torro — one of R.L. Fanthorpe’s pseudonyms, as noted. A sentimental favorite of mine is Robert Sheckley’s The Game of X (1965), which I vividly recall stealing from a summer house that my family stayed in c. 1980.

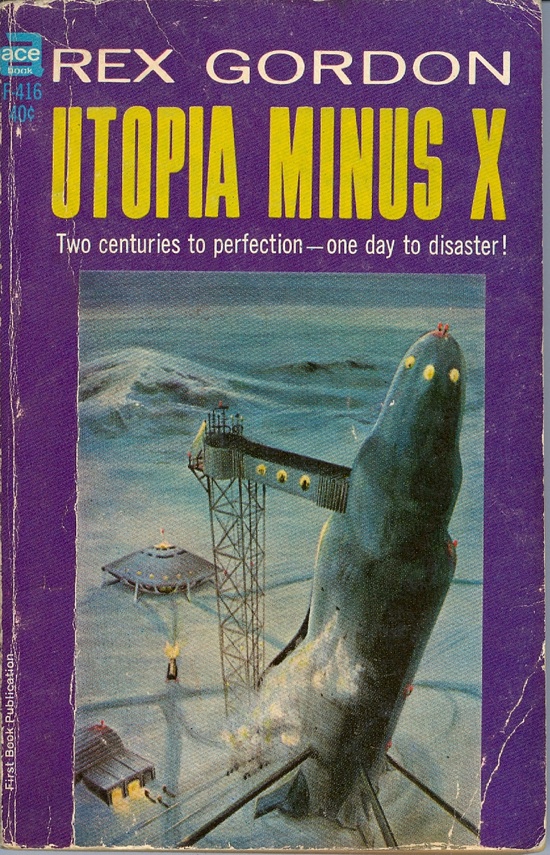

In 1966, we find Rex Gordon’s Utopia Minus X, John E. Muller’s Phenomena X, and Patrick Winn’s Fact X. Michael Avallone’s 1966 romance novel Madame X is a novelization of the movie of that title, which starred Lana Turner and John Forsythe. In 1966, we also find Phenomena X by John E. Muller, who — as previously noted — is actually R.L. Fanthorpe. Fun fact about Utopia Minus X: It was reissued in England in 1967 as The Paw of God, thus reversing the trend toward reissuing mystery and SF books in order to get an “X” into the title. A sign of this viral meme’s imminent demise…

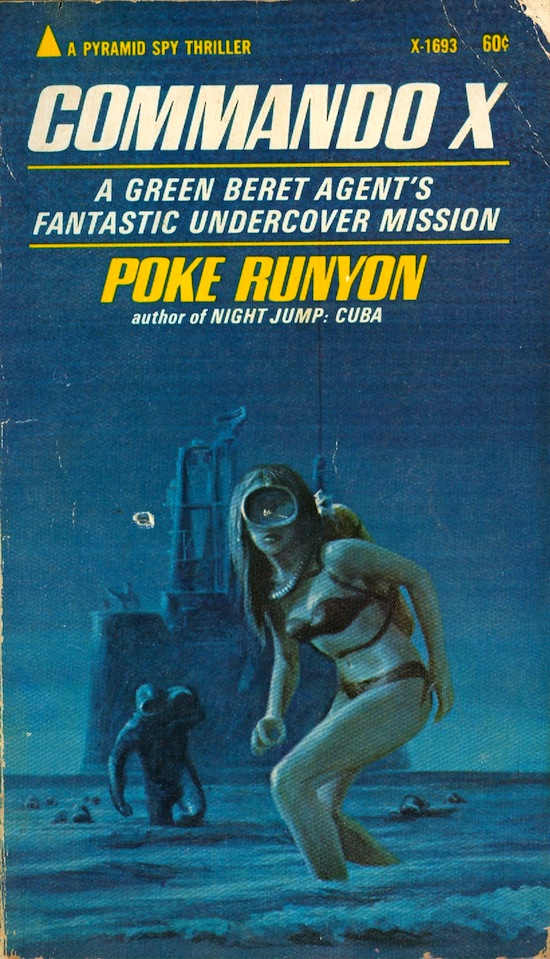

The year 1967 sees the publication of Poke Runyon’s Commando X and Jack Lancer’s X Marks the Spy, the first installment in the Christopher Cool, Teen Agent series. In 1968, we find Arthur Sellings’s sci-fi thriller The Power of X (1968) and Colin Robertson’s Project X (an Alan Steel thriller). Fun facts: Carroll “Poke” Runyon is a former Green Beret and occultist. Shortly after publishing Commando X, he founded the Ordo Templi Astartes, which was dedicated to the revived worship of the Canaanite goddess Astarte and her consort Baal; he later founded also the Church of Hermetic Sciences.

In 1969, we find Christie Harris’s Let X Be Excitement, which I believe is an aviation adventure; and John Morgan’s Death to Comrade X, and Formula 29X by Pel Torro (aka R.L. Fanthorpe).

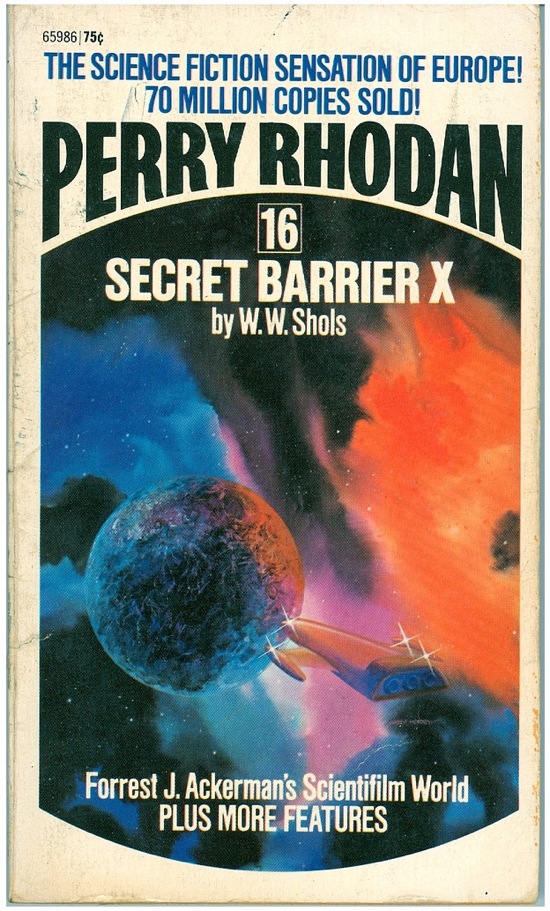

W.W. Shols’s Perry Rhodan sci-fi adventure Secret Barrier X, published in 1972, brings this (incomplete, I’m sure) survey to an end.

Notes on a handful of post–Sixties X books:

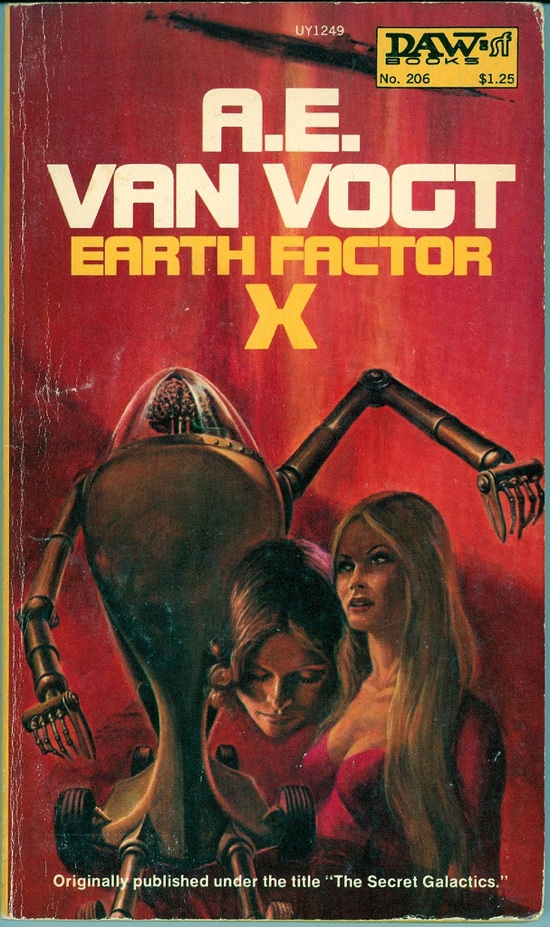

Originally published in 1974 as The Secret Galactics, A.E. Van Vogt’s retitled Earth Factor X (1976) is a straggler. Also worth mentioning is 1975’s Christopher Lee’s ‘X’ Certificate (1975), a horror story anthology exploiting actor Christopher Lee’s star turn in — at that point — over 100 horror films. And of course Hunter Adams’s The Man From Planet X erotic adventure series, already noted above.