Zuni Polychrome Indian Figure Toothpick Holder © Medicine Man Gallery

Originally published in 2007, by Slate.

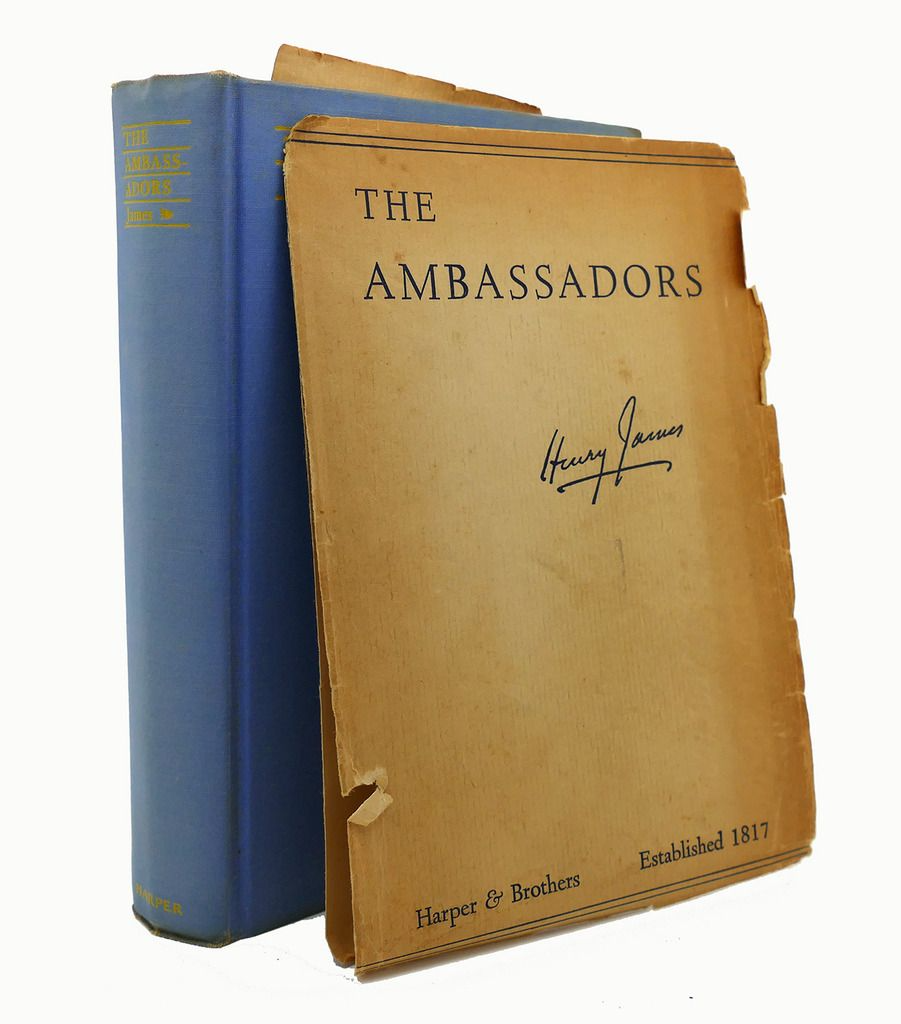

Ever since the 1903 publication of Henry James’ The Ambassadors, critics and readers have puzzled over a literary mystery that has come to be known as the Woollett Question. What, everyone from E.M. Forster to David Lodge has wanted to know, is the “little nameless object” manufactured in Woollett, Mass.? The case went cold at some point in the 1960s, but earlier this week it was reopened… and cracked.

In James’ late and longiloquent novel, our protagonist is Lewis Lambert Strether, the middle-aged amanuensis and aspiring fiance of Mrs. Newsome, a wealthy widow who presides over the fictional manufacturing town of Woollett. Strether is traveling from Boston to Paris, where he hopes to track down Mrs. Newsome’s son, Chad, the wayward heir of the family’s booming industry. Along the way, he is befriended by a young American abroad, Maria Gostrey, who soon inquires what, exactly, it is that they manufacture back in Woollett.

“It’s a little thing they make — make better, it appears, than other people can, or than other people, at any rate, do,” says Strether. When prompted to explain further, he again equivocates, describing the business as “a manufacture that, if it’s only properly looked after, may well be on the way to become a monopoly.” Impatient with Strether’s “postponements,” Gostrey asks him whether the article in question is something improper — perhaps even unmentionable?

“Oh no, we constantly talk of it; we are quite familiar and brazen about it,” Strether hastens to reply. “Only, as a small, trivial, rather ridiculous object of the commonest domestic use, it’s just wanting in — what shall I say? Well, dignity, or the least approach to distinction.” The manufactured item is, he concludes, “vulgar.”

Her interest piqued, Gostrey ventures three guesses: Clothespins? Saleratus? (That is, baking soda.) Shoe polish? No, no, and no. Not until the novel’s final chapter will Strether offer to name the “little nameless object.” But at this point in the narrative, Gostrey, whose romantic overtures have been rejected by Strether, no longer cares to know.

Generations of readers have felt differently: One critic after another has speculated about what small, vulgar, everyday item might have been manufactured at the turn of the century in Massachusetts. In the 1920s, several James exegetes took the low road, arguing that Strether’s protestation notwithstanding, the Newsome family was most likely turning out an unmentionable. In his 1925 book, The Pilgrimage of Henry James, Van Wyck Brooks guesses that the object is “a certain undistinguished toilet-article,” by which he means a grooming or personal hygiene product. In Aspects of the Novel (1927), E.M. Forster insists that we can’t know what the “little thing” is, then facetiously claims that it is a button hook — a doohickey used for fastening one’s garments, gloves, or boots.

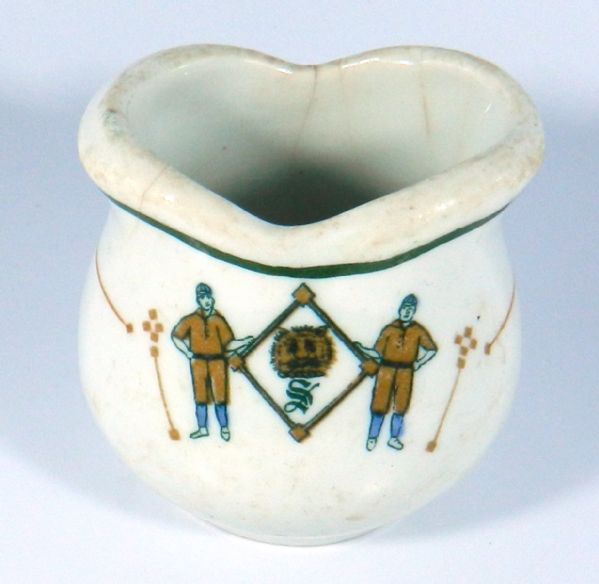

In David Lodge’s 1965 campus novel, The British Museum is Falling Down, Brooks and Forster’s mildly titillating line of interpretation is updated by Camel, a grad student writing a thesis on sanitation in Victorian literature, who suggests that the thingamajig is a chamber pot. One might desire to trust the judgment of Lodge, who is the author of both a novel about James (Author, Author, 2004) and a nonfiction book about his research into James’ life and letters (The Year of Henry James, 2006). But in interviews, Lodge has taken pains to point out that Camel’s scatological theory was advanced only “half seriously.”

Other Jamesians have taken the high road, preferring to believe that Strether’s reluctance to name the object has nothing to do with bodily functions, but instead reflects the expatriated novelist’s own “self-distancing from American business life, whose vulgarities were much criticized by English writers,” as Christopher Butler puts it in his notes to the 1985 Oxford University Press edition of the novel.

In “The Meaning of the Match Image in James’s The Ambassadors,” a 1955 essay in the journal Modern Language Notes, for example, Patricia Evans asserts that the thingamabob is a safety match — which, she claims, would explain why James jokes at one point in the novel that Mrs. Newsome’s daughter’s unpleasant smile was “as prompt to act as the scrape of a safety-match.” The hermeneutics of suspicion is contagious: Two years later, the same journal published “Time and the Unnamed Article in The Ambassadors,” in which R.W. Stallmann, also relying on what might or might not be fraught similes and allegories in James’ text, claims the object “is — or ought to be — a clock.” To be precise, an alarm clock, which “represents a way of life the opposite of Europe’s.”

Alas, without any firm evidence — Stallmann lamely notes that at Worcester, Mass., clocks were manufactured in James’ day, but then sheepishly backs away from this line of argument — we’re still left to guess at what the object might be.

Until now. For years, I’ve had the Woollett Question in the back of my mind: What kind of article would fit every particular? First, the object must be small, trivially so: not a chamber pot, then, nor an alarm clock, the former being too large and the latter insufficiently trivial. Patricia Evans’ safety match is an inspired guess… but matches are neither ridiculous nor vulgar. Second, the article must be something controversial, and therefore likely to have been talked about “constantly,” in late 19th- and early 20th-century polite East Coast society: not a button hook, then, nor most artifacts used in making your toilet. Razors, toothbrushes, menstrual pads, earwax curettes, and the like may have been vulgar, but controversial they were not.

The answer was finally revealed to me a few weeks ago, via a new book by Henry Petroski, prolific author of case histories of “useful things,” from pencils to paper clips to the kitchen sink. His latest is on the toothpick. Writing in the New York Times Sunday Book Review last week, Joe Queenan excoriated Petroski for having written a worthless text. How wrong he was! For although Petroski never mentions James in The Toothpick: Technology and Culture, he nevertheless provides conclusive proof that the “little nameless object” in The Ambassadors, over which so many have brooded for so long, is, yes, a toothpick.

Let’s proceed with caution. Is a toothpick trivially small and ridiculous? Check. Where were ready-made wooden toothpicks first manufactured in America? In Cambridge, Mass., by Charles Forster, an entrepreneur who, in the mid-1860s, oversaw the development of a new device that transformed birch logs into flat, double-pointed toothpicks. Was the toothpick controversial? Yes! According to Petroski, although wooden-toothpick use after meals was a long-standing tradition in Spain and Latin American countries, in mid-19th-century New England, polite society regarded public tooth-picking as vulgar, and the implement was an “unknown adjunct to the dinner table.” Forster slowly overcame this prejudice through assiduous marketing; according to possibly apocryphal legend, his most successful scheme was hiring “Harvard scholars” to eat at Boston restaurants and then after their meal to ask for toothpicks.

By 1869, according to some estimates, machine-made toothpicks were selling in the United States at a rate as high as 5 million per day, and Forster held a virtual monopoly (recall Strether’s use of the term) on their production and sale. In 1882, a year in which James was twice recalled from England to his parents’ home in Cambridge, first by his mother’s death, then his father’s, it was big news around eastern Massachusetts that a factory capable of producing 70,000 toothpicks per hour was going to be established south of Boston, at Brockton. The New York Herald expressed the “hope that the Boston ladies will not imitate some of the New York ladies who carry toothpicks in their mouths in stores and streets.” As for the Forster children, they seem to have been no more proud of their family’s enterprise than the Newsomes. Petroski notes that when Charles Forster died in 1901, two years before the publication of The Ambassadors, his family would neglect to mention in his obituary his pioneering work in making and marketing toothpicks.

The foregoing evidence, I submit, is stronger than anything that other Jamesians have produced so far. But there’s textual proof as well. In looking through James’ other writings, the references to toothpicks I’ve found suggest he indeed considered the item vulgar. For example, in an 1870 magazine article, “Saratoga,” James contrasted the sophisticated European leisure class with the American men he found in the portico of the Union Hotel, in the resort town of Saratoga Springs, N.Y.:

They come from the uttermost ends of the continent — from San Francisco, from New Orleans, from Duluth. As they sit with their white hats tilted forward, and their chairs tilted back, and their feet tilted up, and their cigars and toothpicks forming various angles with these various lines, I imagine them surrounded with a sort of clear achromatic halo of mystery.

In an 1884 story, “Pandora,” a Jamesian party of upper-class picnickers returns to Washington, D.C., from a cruise along the Potomac:

There was some delay in getting the steamer adjusted to the dock, during which the passengers watched the process over its side and extracted what entertainment they might from the appearance of the various persons collected to receive it. There were darkies and loafers and hackmen, and also vague individuals, the loosest and blankest he had ever seen anywhere, with tufts on their chins, toothpicks in their mouths, hands in their pockets, rumination in their jaws and diamond pins in their shirt-fronts, who looked as if they had sauntered over from Pennsylvania Avenue to while away half an hour, forsaking for that interval their various slanting postures in the porticoes of the hotels and the doorways of the saloons.

In his 1884 story “Georgina’s Reasons,” also written during or shortly after his last visit to America, James once again suggests that the better sort of person does not chew on toothpicks:

It was not striking to Captain Benyon why Percival Theory had married the niece of Mr Henry Platt. He was less interesting than his sisters — a smooth, cool, correct young man, who frequently took out a pencil and did a little arithmetic on the back of a letter. He sometimes, in spite of his correctness, chewed a toothpick…

Perhaps my favorite piece of textual evidence, though, comes from The Ambassadors itself. In the 1880s, Forster patented a revolutionary new machine that polished, rounded, compressed, and sharpened toothpicks. This new toothpick was a marvel, according to Petroski, “ahead of its time as a designed object.” Now consider Strether’s first impression of Chad Newsome, whom he hasn’t seen in five years when he finally tracks him down:

Chad was brown and thick and strong; and of old Chad had been rough. Was all the difference therefore that he was actually smooth? Possibly; for that he was smooth was as marked as in the taste of a sauce or in the rub of a hand…. It was as if in short he had really, copious perhaps but shapeless, been put into a firm mould and turned successfully out.

James had a habit of associating his characters with a specific piece of scenery or work of art, or, in The Ambassadors, manufactured object — recall Sarah Newsome Pocock’s safety-match smile. Of Chad Newsome, it might be said that he was as compressed and polished as one of Forster’s toothpicks.