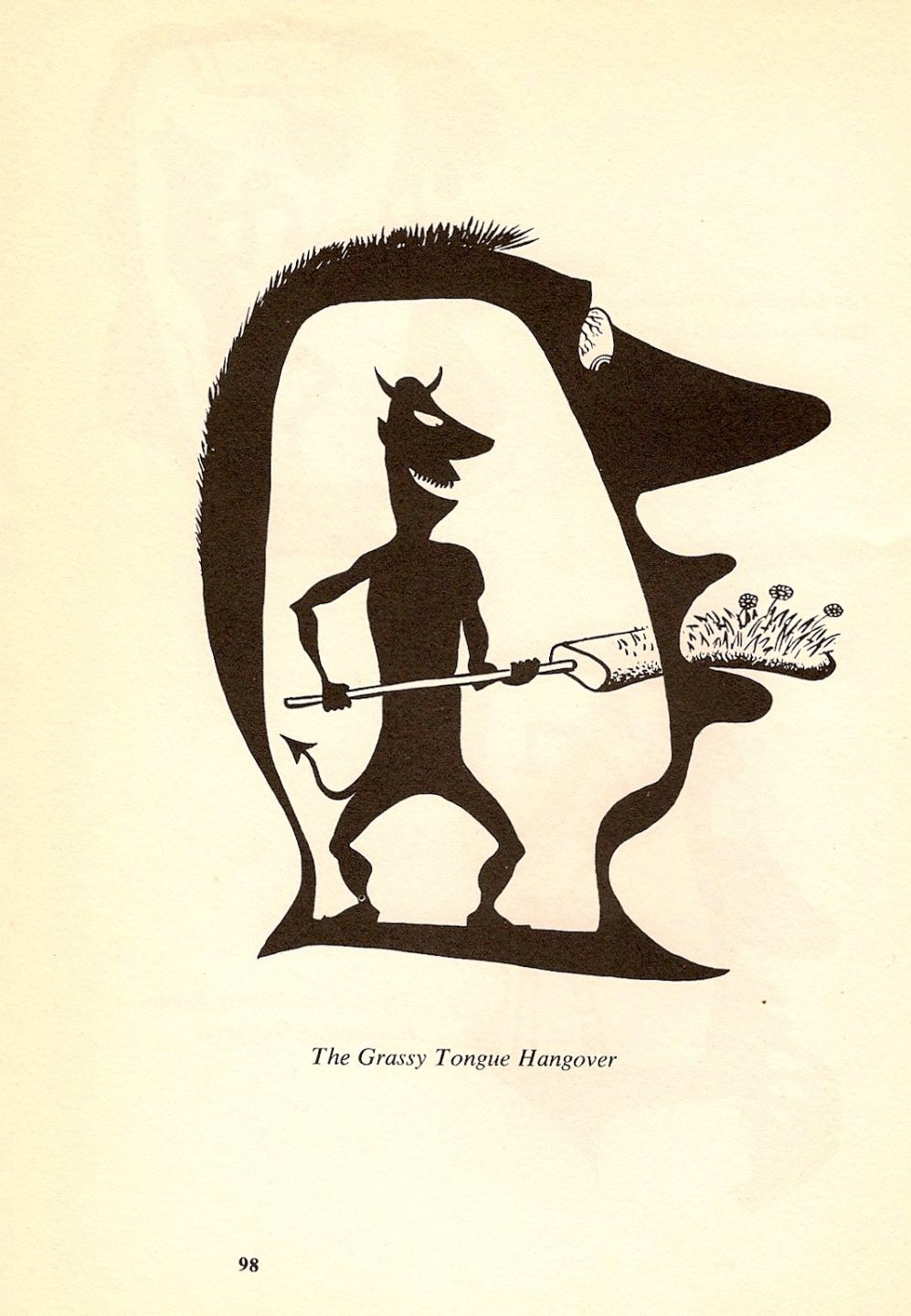

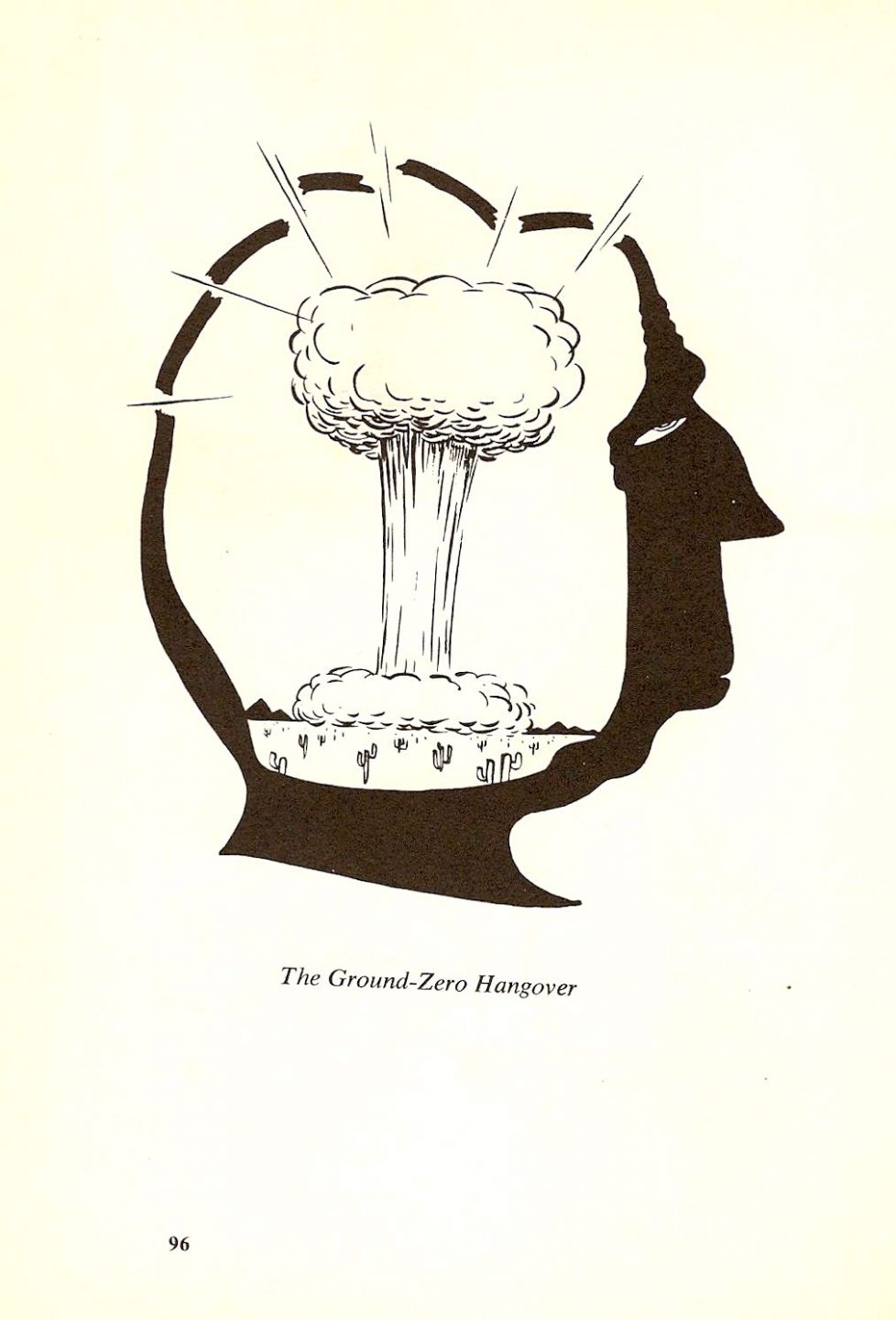

Hangover cartoon by VIP

Originally published in 1996, in The Idler.

Whenever hangovers become the topic of conversation at the swanky sorts of cocktail parties I too often frequent, some would-be professional inebriate inevitably feels compelled to burden the entire gathering with the insight that there is no such thing, really, as a hangover remedy. Because God knows (we’re supposed to infer), if such an elixir did in fact exist, this reincarnated Dean Martin would surely have discovered it by now.

Bullshit. Two aspirins and a gallon of water, taken while still drunk, will do the trick every time. I discovered and perfected this routine in college where, after long days and nights of guzzling funnels-full of warm Blatz between shots of 101-proof Wild Turkey, as my compatriots lay strewn mid-revel about whatever living room we’d invaded in as though overcome by carbon monoxide fumes, I’d shakily but purposefully choke down glass after glass of H2O, never allowing myself to black out until I’d shipped enough liquid to irrigate Fenway Park. I even took to carrying a small tin container of extra-strength aspirin with me wherever I went, since I kept inexplicably finding myself shackled to hogsheads of malt liquor in unfamiliar dormitories.

These preventative measures, plus my much-imitated habit of forcing myself to vomit after every ten beers (in order to make room for more), worked perfectly: I was the only one of my friends who never lolled about on a Sunday morning poetically lamenting a richly appointed headache, a mouth that Kingsley Amis’s gerbil had nested in, eyeballs dripping blood, or a gaseous ferment of the innards. Instead, I leaped out of bed each day full of vim and vigor, and applied myself industriously to the task of self-improvement. I now regret all those hours I wasted back in the days, and often wonder what I might have learned had I occupied my time in a more enlightened fashion. No, I don’t regret all the drinking; what I’m sorry about is all the hangovers I missed.

This is, I know, a strange thing to claim, since the hangover is one of our culture’s favorite bugaboos, more feared even than male pattern baldness or the heartbreak of psoriasis. (Witness the seemingly bottomless well of hangover jokes that ’50s-’60s cocktail-era cartoonists like Vergil “VIP” Partch drew from for their men’s magazine illustrations, or SKYY vodka’s vague promises of consequence-free pleasure.) I now believe, however, that my own misguided attempts to avoid becoming hungover have been a betrayal of and an impediment to whatever is good and noble about getting blotto in the first place. I recant.

So what’s good about a hangover? Everything (except the headache, maybe) that you think you hate about it. The hungover person is abnormally aware of sights, sounds (everything seems TOO LOUD!), tastes, odors, and textures which normally would go unremarked. That’s a good thing, not a bad thing. The hungover eye, for instance, because it is neither obstructed by the blinders of our everyday biases, nor deceived by intoxicated hallucinations, is magnetically attracted to seemingly ordinary objects which take on an incredible, luminous significance: anyone who has ever experienced the “stares” when hungover knows exactly what I mean.

Although the sudden awareness of the sacred in the mundane is what most religious traditions refer to as nirvana, or some type of grace, we too often shrug off these moments in our haste to get rid of our hangovers. (I suspect, actually, that the hungover eye which is somehow between the appraising eye of the teetotaler and the foggy eye of the drunkard may be the model for Hinduism’s “third eye” of enlightenment.) Thus it is that the moment of the hangover can propel us into a “middle state” of perceptivity quite unlike anything we’re ever likely to experience outside of a monastery.

The manner in which we perceive the world and the manner in which we exist in it are inextricable, however, so it should come as no surprise that in my studies I’ve found several visionaries who have taken practical inspiration from the hangover. The poet William Corbett, for example, once wrote frequently about his own hangovers: e.g., “For breakfast aspirins/a glass of milky water./I am always just/learning how to live… .” (“Depression,” St. Patrick’s Day, 1976). I find something heartening in Corbett’s notion that when we are neither sober nor drunk we have an opportunity to start over. Having experimented with mescaline, in The Doors of Perception (1954) Aldous Huxley writes that although he was delighted to have been freed from “that half opaque medium of concepts” which obscures from our ‘straight’ powers of perception “the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence,” we cannot live day to day in such a fashion. He suggests instead that we strive to “be aware, always, of total reality in its immanent otherness — to be aware of it and yet to remain in a condition to survive as an animal, to think and feel as a human being, to resort whenever expedient to systematic reasoning”: in other words, we should try to perceive and behave at all times as though hungover.

One final example is the Zen master Shunryu Suzuki, who teaches in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970) that “When you wake up in the morning, I think you do not feel so well. Your mind is full of ‘weeds’ … But if you can cease striving to overcome those weeds, they, too, can enrich your path to enlightenment.” I suspect that Suzuki-roshi’s translator didn’t understand that “mind-weeds” is Zen slang for a hangover.

Why do we assume that intoxication leaves us with nothing the next morning but physical pain? Because we’ve been educated to feel that way. Books and articles on the subject of intoxication discuss at length the difference between being drunk and being sober, yet they never explore that unavoidable duration of time during which one painfully returns from ecstasy to mundanity. A related phenomenon is our sentimental fascination with the fun, romantic part of pilgrimages: we love accounts of life on the road, where one is freed from the uptight constraints of the social order left behind, but we don’t like the part where the pilgrim must return home and begin the difficult task of putting his or her newfound insights to the test. If drinking can be compared to a pilgrimage — in both, after all, one leaves the usual for the unknown — it is clear that the lived experience of the hangover merits more attention than the usual clichés about ice-packs and people SPEAKING TOO LOUDLY.

This is the hangover’s hangover: we forget the moments of enlightenment, and only remember the ringing ears and the disequilibrium. If the hangover can indeed be accounted as a form of reaggregation from the extraordinary into the ordinary, as a ‘middle state’ of perception in which one can for a brief time see the usual in an unusual manner, it’s no wonder that our culture doesn’t want us to enjoy it. Our socially imposed conscience is that which the imbiber seeks to escape, yet somehow our conscience always gets its revenge by convincing us that the only consequence of crapulous excess is pain.

So the next time you wake up with your tongue stuck to an empty bottle of Thunderbird, just take the lyrics to Diana Ross’s “Love Hangover” as your mantra: “If there’s a cure for this, I don’t want it!/If there’s a remedy, I’ll run from it!/I’ve got the sweetest hangover [that] I don’t wanna get over!”