Carl Spackler

This is the seventh installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

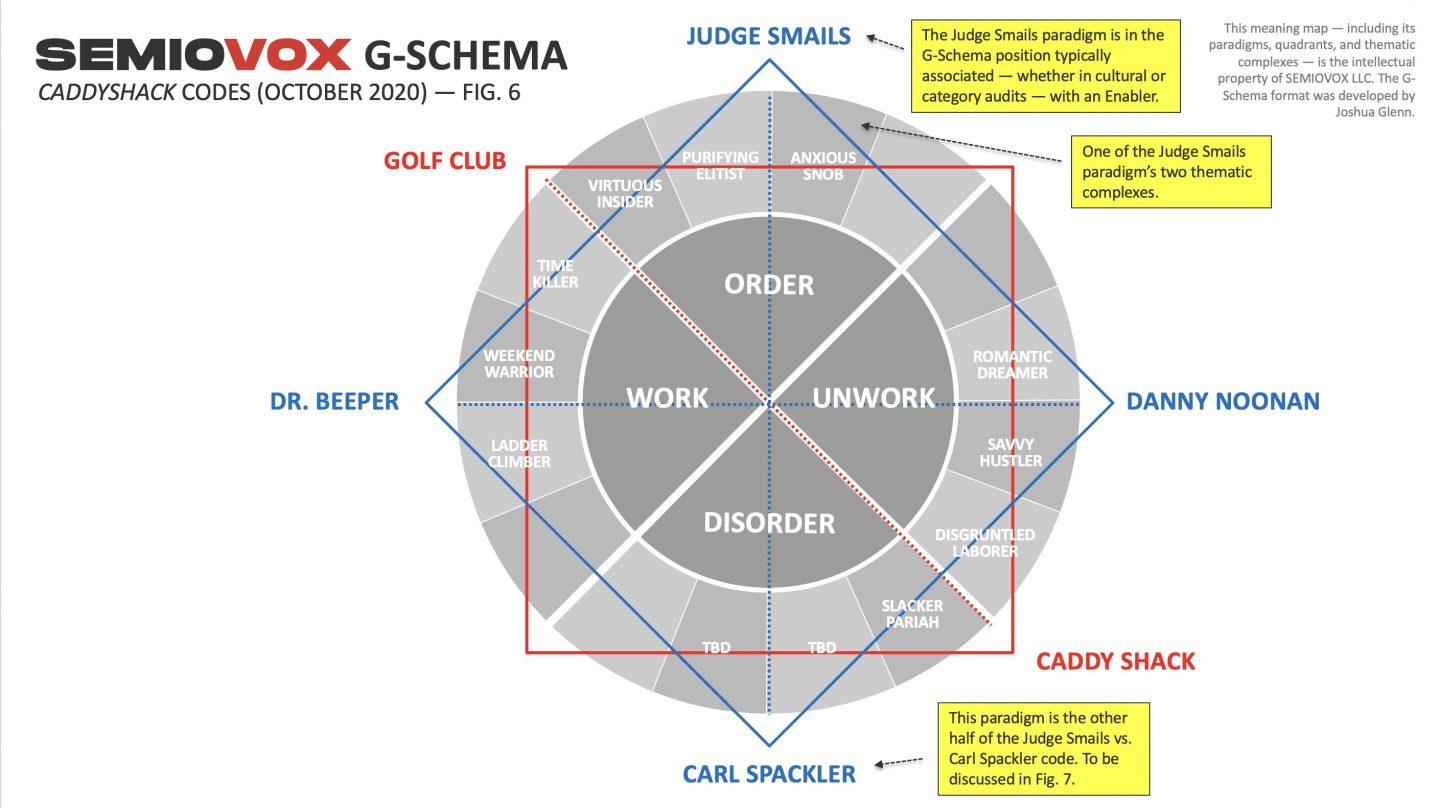

By the end of this series’ sixth installment, we’d arrived at the semiosphere-mapping stage illustrated in Fig. 6 (below). Our meaning-map’s “master code,” Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack, has been thoroughly explicated, its thematic complexes brought to life via a range of associated source codes (“signs”); the same goes for our second code, Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan. And now we’ve begun to unpack our third code.

In the previous installment, I offered an analysis of the paradigm Judge Smails; here, we’ll look at its opposing paradigm: Carl Spackler.

This opposition might come as a surprise. After all, Judge Smails and Carl Spackler barely interact, at all, during Caddyshack. However, having unearthed the deep cultural drivers at play, via semiotic analysis, we are able to see Caddyshack with a fresh perspective. If ORDER vs. DISORDER is one of the deep binary oppositions animating this cultural production, and if the Judge Smails paradigm governs ORDER, then… yes, the Carl Spackler paradigm governs DISORDER. It makes perfect sense, now.

PS: In this series’ second installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed (over the past 20+ years) in order to productively and insightfully map any product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s network of meaningfulness.

☸

In constructing each new G-Schema, I proceed in a tried-and-true fashion — the idiosyncratic methodology of which this series aims to demonstrate.

Paradigm

As noted in this series’ previous installment, the top-most vertex in a G-Schema represents a semiosphere’s “ego” — that is to say, a paradigm that is deformed by its efforts to mediate between the master paradigm (in this case, Golf Club) and the antiheroic top-right vertex, our semiosphere’s “id.” The “ego” paradigm may bloviate and posture, but it’s an insecure enabler.

The bottom-most vertex in a G-Schema is a semiosphere’s “anti-ego”: that is, an inchoate self-under-construction, a wide-eyed innocent, a rebel without a cause, a romantic seeker, a prat-faller. (Think of the Tarot’s Fool, setting off on a romantic adventure… but immediately tumbling off a cliff. Or think of Baudelaire’s poète maudit, “stumbling on words as on cobblestones.”) If Smails is a “complex” meta-term or figure (to use Greimasian terminology) emerging from the “unmarked” opposition between two of the semiosphere’s unmarked and marked terms (the Country Club and Ty Webb, respetively), then Spackler is a “neutral” meta-term or figure emerging from the “marked” opposition between two additional unmarked terms: the Caddy Shack and the term at bottom left, to be explicated in a subsequent post. Greimas describes the neutral meta-term as one in which all the semiosphere’s “negations and privations” are assembled; it’s certainly the case that whereas Smails seems to have it all, Spackler seems to have nothing at all. (I say “seems,” because here, as in other narratives, we’ll find that the figure who seems to have it all, in important respects actually has nothing; and vice versa.)

More on the anti-ego, and on fools/clowns…. Like the Smails character, the Spackler character is — psychologically speaking — caught in what Gregory Bateson would describe as a “double bind.” This figure can’t win. If intensified and prolonged, Bateson would have us understand (in a 1956 essay collected in 1969’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind), a double-bind situation can lead to a person becoming “a clown, a poet, a schizophrenic, or some combination of these.” If Smails is a clown, then Spackler is more of a poet and a schizophrenic.

In Chris Nashawaty’s 2018 book Caddyshack: The Making of a Hollywood Cinderella Story, we learn that the character of Spackler doesn’t make a single appearance in the script’s first draft. Like a gopher burrowing its way into a golf course, somehow Spackler established himself as a subversive force within the movie’s semiosphere. This turn of events is usually chalked up to Bill Murray’s charisma; invited to make a brief cameo by Harold Ramis and his own brother, the movie’s coauthor Brian Doyle-Murray (who plays Lou Loomis), Bill’s ad-libbing was so brilliant, his rubbery facial expressions so amusing, that the groundskeeper’s minor role metastasized.

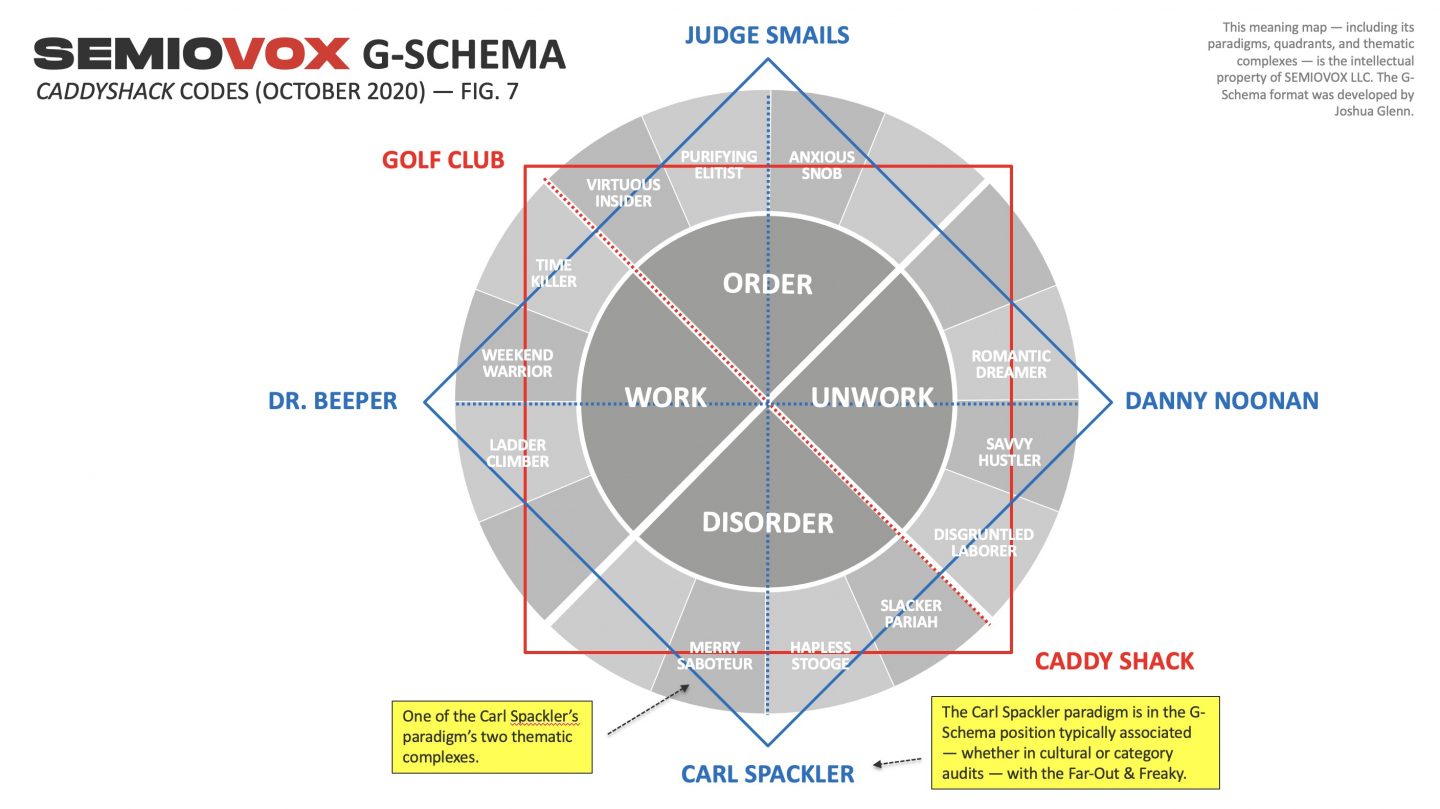

As the preceding notes suggest, the bottom-most vertex paradigm can be a far-out and freaky one — visionary, perhaps, but also kooky. In life as in art, of course, it can be very difficult to untangle the two. We’ll turn now to an investigation of the paradigm Carl Spackler’s two (far-out and freaky) contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes.

Adapting and building upon the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Carl Spackler categorical proposition like so: “It shall not be the case that Caddy Shack is Golf Club.” The two paradigms flanking Caddy Shack, on our diagram, are not entirely persuaded by that paradigm’s counter-discourse; unlike the slackers of the Caddy Shack, then, they are driven to combat the Golf Club’s ideological apparatchiks; in Carl Spackler’s case, the direct conflict is with Judge Smails.

According to my analysis, as Fig. 7 (above) indicates, the thematic complexes Hapless Stooge and Merry Saboteur are central to the Caddyshack semiosphere’s DISORDER quadrant. The movie needs this subversive, antic, chaotic paradigm — to oppose the fiercely controlling paradigm Judge Smails. Without Carl Spackler, this movie would never have become a cult classic… and we wouldn’t be analyzing it today.

Hapless Stooge

Early on in the movie, when Judge Smails berates Bushwood’s groundskeeper, demanding that he exterminate the invading gopher he’s spotted, the put-upon Scotsman promises that “I’ll put my best man on it.” Cut to Carl Spackler, clad in a sweat-stained t-shirt and camouflage bucket hat. He’s ogling the club’s frumpy, sexless older female golfers, and muttering vile nonsense to himself — while masturbating, at least as far as we can tell. The groundskeeper’s best man, we immediately understand, is a bozo.

Spackler does the dirty work, at Bushwood. He tends to operate behind the scenes, often after dark. He’s an invisible man, toting gear and even weaponry from place to place within Bushwood’s confines, all but unnoticed by the club’s oblivious members. He’s a stooge, in the original slang sense of the term: an underling. And like the Three Stooges vaudeville and screen act, he’s not very good at his job; in fact, he screws up at every opportunity.

Tasked with killing “all the gophers” (at 8:50), Spackler’s initial response is one of confusion — he thinks the groundskeeper wants him to kill all the golfers. His next move is to slack off. (Note that, on our meaning-map, the thematic complex Hapless Stooge is adjacent to the thematic complex Slacker Pariah.) At 10:30, instead of killing gophers Spackler is pressing a pitchfork to D’Annunzio’s brother’s neck and telling a tall tale about his youthful exploits as a “looper” (caddy), including a round of golf in Tibet with the Dalai Lama.

Thanks to Murray’s memorable delivery, many of us can recite these lines: “He hauls off and whacks one — big hitter, the Lama — long, into a ten-thousand-foot crevasse, right at the base of this glacier. Do you know what the Lama says? Gunga galunga… gunga, gunga-lagunga.” The conclusion to this anecdote, in which the Dalai Lama doesn’t tip his caddy, but instead promises that he will receive “total consciousness” on his deathbed, is a tragicomic one. Obviously the Dalai Lama (if this incident happened at all) was bullshitting the gullible Carl. But he’s a wide-eyed visionary, and he wants to believe that it’s true: “So I got that goin’ for me, which is nice.”

It’s in these sorts of moments that we can perceive how the Hapless Stooge is opposite to — in terms of the Caddyshack semiosphere — the Anxious Snob. An anxious snob like Smails doesn’t really believe in himself, which is why he insists with such vehemence that everyone show deference and respect — to Bushwood, and by extension to himself. He’ll prove himself willing to do whatever it takes to keep up appearances. Spackler, meanwhile, doesn’t keep up appearances at all; he’s a hot mess, he lives in squalor; he parties hard. Yet his faith in himself is unshakeable — he remains convinced that he is en route to fulfilling some sort of purpose.

This purpose-driven aspect of the Spackler character comes out in Murray’s one scene with fellow SNL cast member Chevy Chase. Eager to impress Ty, whom he sees as a potential friend, Carl blurts out his hopes. “People say, you know, I’m an idiot or something,” he laments (1:16:29), before explaining that he’s invented his own golf-club turf varieties, including one that is “a cross, uh, bluegrass, Kentucky bluegrass, uh, featherbed bent, and, uh, northern California sensimilla” (1:17:03). He’s also been studying up on what it takes to become a head groundskeeper. We may snicker at Carl’s misguided vision, but… everyone loves a visionary. Maybe he’s a genius?

Back to Carl’s haplessness, though. At 23:15, he hauls a hose to the gopher’s hole in the most obscene way possible. Pausing, before he turns the water on (23:50), to make an ominous speech (“I think it’s time somebody teaches these varmints a little lesson about morality…”), we get the sense that Spackler is living in his own fantasy world. He has cast himself as the star of a gritty vigilante flick like Billy Jack (1971) or Death Wish (1974), say; or perhaps it’s a Dirty Harry movie. As the gopher subplot evolves, Spackler’s fantasy will become more militarized — until he’s singing “The Ballad of the Green Berets.”

In fact, the hapless Carl is more like Wile E. Coyote than Dirty Harry. He devises ever more elaborate varmint-killing plans which backfire in spectacular fashion. At 32:33, for example, Spackler creeps around the golf course at night, with a powerful flashlight taped to a rifle, drinking beer and still muttering to himself. He nearly kills Ty and Lacey, before slinking away again.

Later (at 1:14:05), we’ll find Spackler in his squalid shack, forming plastic explosives into the shapes of gophers and other critters. He squashes one of his creations with a fire extinguished, laughing maniacally. He’s losing his shit. I’ll stop talking about the gopher subplot here, though, because we’ll return to it in the Merry Saboteur section of this post. The point is, however, that Carl may be a dangerous psychotic. Soon after this moment, he’ll offer — as a gesture of friendship to Ty Webb — to cut Judge Smails’s hamstring (1:18:33). Ha ha?

At the movie’s midpoint, Spackler seems to have forgotten about the gopher. In his only scene involving Judge Smails, Carl bites into the candy bar which everyone in the pool had mistaken for a poop. Like a Shakespearean Fool, he is speaking truth to power — Smails’s outraged campaign to sterilize the pool is misguided — but his capricious antics ensure that he won’t be listened to. There’s another truth-telling moment at 1:18:22, when Carl tells Ty — who is obviously freaked out by the money match he’s unwillingly agreed to play — that “You been acting psychotically lately. What the hell? What the hell? Why?” Instead of seeking to escape from Carl’s lair, Ty should lie down on the couch and spill his guts.

Carl next surfaces at 1:01:16, daydreaming about being a great golfer and whacking the heads off the groundskeeper’s flowers with a gardening tool. It’s a short scene, but Murray’s improvised lines are among the movie’s most memorable:

What an incredible Cinderella story. This unknown comes out of nowhere to lead the pack. At Augusta, he’s on his final hole. He’s about 455 yards away. He’s going to hit about a two iron, I think. Well, he got out of that. The crowd is standing on its feet, here at Augusta. The normally reserved Augusta crowd is going wild. For this young Cinderella who’s come out of nowhere, he’s got about 350 yards left. He’s going to hit about a five iron, l expect. Don’t you think? He’s got a beautiful back swing. That’s — oh! He got out of that one! He’s got to be pleased with that. The crowd is just on its feet here. He’s a Cinderella boy. Tears in his eyes, I guess, as he lines up this last shot. He’s got about 195 yards left, and he’s gonna — looks like he’s got about an eight iron. This crowd has gone deadly silent. Cinderella story. Out of nowhere. A former greenskeeper now about to become the Master’s champion. It looks like a miraculous — it’s in the hole! It’s in the hole!

Again, we may laugh at the outlandishness of his vision… but we love a visionary. We don’t know whether or not to believe in Carl; he’s uncanny.

Carl goes straight from this iconic moment into caddying for the bishop, during a torrential thunderstorm (1:03:28). It’s another classic scene, at the end of which he again slinks away — leaving the bishop, who has been struck by lightning, for dead. In this task, as in every other one we have watched him undertake, the visionary seeker has failed utterly, beautifully.

Merry Saboteur

As Fig 7 indicates, the thematic complex Merry Saboteur is opposite the Purifying Elitist complex. Whereas a purifying elitist like Smails is unhappily obsessed with patrolling borders and preserving boundaries, a merry saboteur gleefully crosses borders, defiling and despoiling. Note, however, that a saboteur is not an outsider seeking entrance; the saboteur has foxily made his or her way inside the institution to be destroyed.

Carl Spackler and the gopher play a similar role within the Caddyshack semiosphere. Everything they do serves to undermine the order and stability of Bushwood; in the gopher’s case, this undermining is literal. As Carl seeks to destroy the gopher, he becomes more like it. “I have to think like an animal,” he tells himself (at 1:14:05), “and whenever possible to look like one.” By the movie’s end, it is Carl who literally undermines Bushwood.

As mentioned above, Carl is this semiosphere’s “anti-ego,” if you will. He apes the ego, but incompetently — and in doing so, he satirizes the ego and its goals. At 23:45, for example, when he first sets out to kill the gopher, he makes bombastic, Smails-esque remarks about teaching the gopher to be a “decent, upstanding member of society.” As soon as the gopher bites his finger, however, he abandons this rhetoric. Casting about for a new narrative framework, as inchoate anti-egos are wont to do, he quickly settles on a Vietnam War action movie storyline, in which he is a valiant soldier and the gopher is the Viet Cong. He is John Wayne in The Green Berets (1968), or perhaps he’s imagining The Boys in Company C (1978).

Like the Viet Cong, the gopher is unkillable; Carl’s escalating tactics are ultimately injurious only to Bushwood. At 24:20, he floods the gopher’s hole with water, only to end up dousing the entire golf course. At 29:00, we find Carl hunkered down in his shack, where sacks of fertilizer resemble the sandbags of a GI’s foxhole. As he tinkers with his weapon, he narrates the voiceover of an action movie, and hums its dramatic theme song too. As he rants about the “Varmint Cong,” we realize that Spackler is actually in a movie about a psychologically damaged Vietnam War vet — Taxi Driver (1976), say, or Rolling Thunder (1977), or perhaps The Deer Hunter (1978).

Like a Vietnam vet, Carl yearns for respect. “I will teach you the meaning of ‘respect,'” he mutters (37:45) as he ogles the club’s older female golfers. Unlike Judge Smails, though, who obtains the respect that he also craves thanks to his elevated social status, for Carl respect is as unobtainable a goal as a military victory in Vietnam. The last time we see Carl, in Caddyshack, he is completely unhinged. Crawling on his belly, he drops plastic explosives into the gopher’s holes; at one point (1:28:45) he even bites the head off a squirrel-shaped wad of plastique. At 1:30:50, he sings the “Ballad of the Green Beret” song — “Silver Wings upon their chest / These are men America’s best” before blowing up the entire golf course.

Carl isn’t the movie’s only saboteur. As mentioned, there’s also the gopher — a character added in post-production, much to Harold Ramis’s chagrin. There’s also Portherhouse, who purposely destroys Smails’s golf shoe (17:35) after overhearing the judge tell a racist joke. The Bishop, too, becomes a saboteur of sorts — after he’s struck by lightning after barely failing to beat the golf course’s best score. He becomes a Hemingway-esque drunk, growling (at 1:09:38) that “There is no God.”

Bushwood’s caddies, too, at one point threaten sabotage. We’ve discussed their invasion of the club’s pool already, in this series’ third installment. But we didn’t get into the details of their behavior, at that point; let’s do so now.

As you’ll recall, the caddies are permitted to use the club’s pool for a lousy 15 minutes during a single day each summer: Caddy Day. Their very presence in the pool is horrifying to Bushwood’s members — particularly when they flagrantly defy the clubhouse rules. But they do more than merely defy the rules. The pool scene — which happens at the movie’s midpoint — is a carnivalesque scene of revalued values, a momentary triumph of disorder over order. There is a ritual quality to the caddies’ behavior; it’s a comic version of a horror movie like The Wicker Man (1973). One also thinks of the revenge — violent, sexual — of the peasants on the lord of the manor, for example in the 1971 thriller Straw Dogs. The water ballet scene is funny — and also terrifying, suggesting as it does not random chaos but an organized mission of subversion, and/or a Satanic rite.

Things escalate at 46:31, when the lifeguard and his chair are hurled into the pool. When next we see the lifeguard, at 47:34, a topless female caddie is riding on his shoulders. He seems to be enjoying himself. This is turning into a general strike; the cops have joined the rioters. Where will it end? The “turd” candy bar in the pool, in fact, is what saves Bushwood from further riot and ruin. Caddies and Bushwood members alike flee the scene.

What can we predict about the meaning-map’s bottom-left paradigm, in light of what we now understand about the adjacent Merry Saboteur complex? We know that this paradigm will be at least in part a disorderly figure, threatening to disrupt the sanctity of Bushwood — and perhaps to imperil its very existence. Also, as we analyze the continuum of thematic complexes within the map’s DISORDER quadrant, we see that the Slacker Pariah is an outsider, while the Hapless Stooge and Merry Saboteurs are outsiders who have wormed their way inside. The bottom-left paradigm, then, will be something even stranger: an outsider who by all rights could become an insider, but who for some reason resists the temptation to do so.

There you have it: the second half of Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler, our Caddyshack meaning map’s third code. I’ve identified the paradigm Carl Spackler’s contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. I’ve established not only what Carl Spackler means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the character — but how this paradigm means what it means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts to facial expressions, clothing, mannerisms, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what Carl Spackler signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

This series’ next installment, on the paradigm Ty Webb, explores the first half of the Caddyshack semiosphere’s fourth and final code.