Ty Webb

This is the eighth installment in a series of posts offering a semiotic analysis of the 1980 golfing comedy Caddyshack. (Why select this particular, not very successful, deeply flawed movie? See the series introduction.)

In this series’ second installment, I introduced SEMIOVOX’s G-Schema, a purpose-built tool that I’ve developed (over the past 20+ years) in order to productively and insightfully map any product category’s, cultural territory’s, or cultural production’s “semiosphere” — which is to say its network of meaningfulness, a matrix of values and disvalues that subtly helps shape and guide perceptions and sense-making within this space.

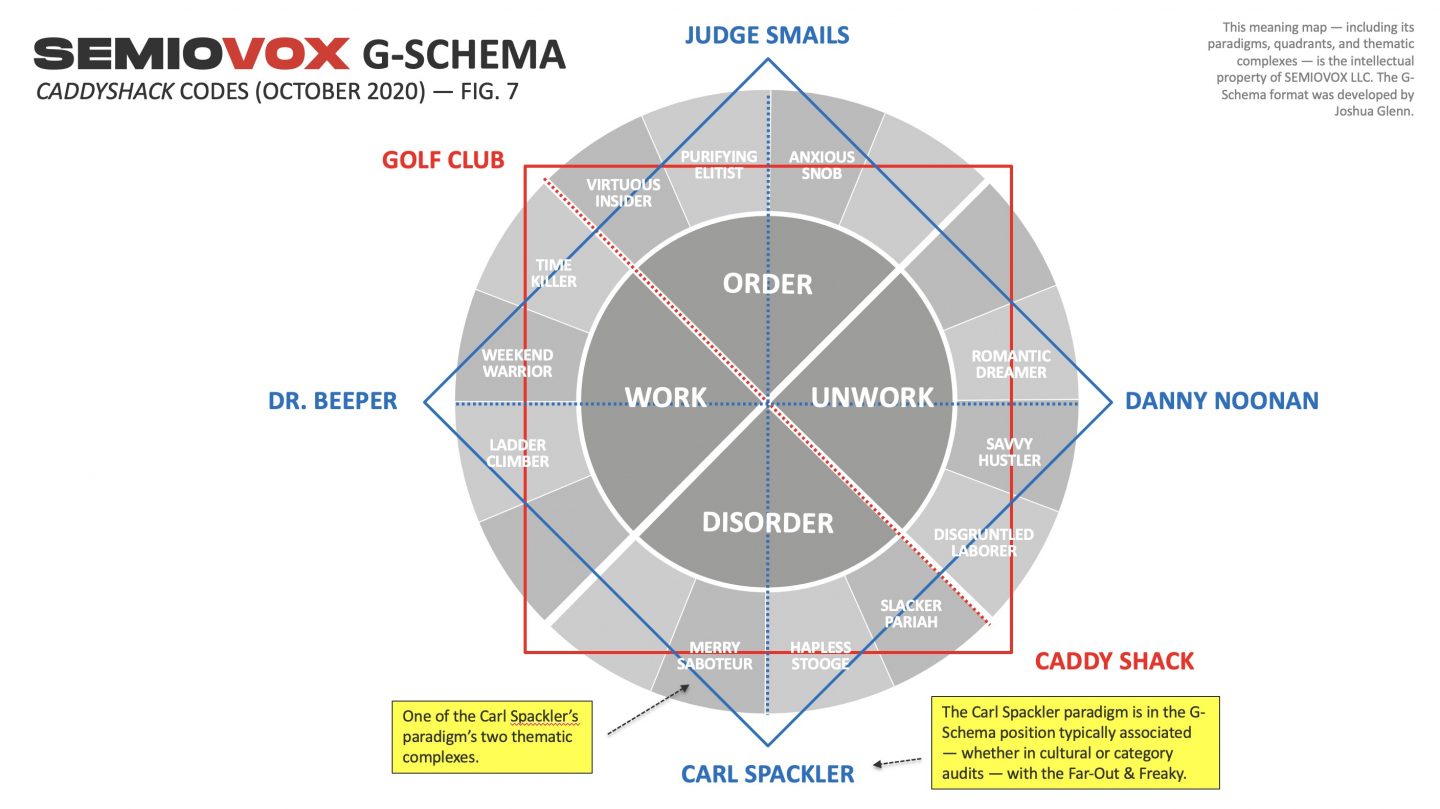

By the end of this series’ seventh installment, we had arrived at the semiosphere-mapping stage illustrated in Fig. 7 (below). Our meaning-map’s “master code,” Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack, has been thoroughly explicated, and its thematic complexes brought to life via source codes (“signs”) surfaced and dimensionalized through my analysis of the movie; the same goes for this semiosphere’s second code, Dr. Beeper vs. Danny Noonan, as well as its third, Judge Smails vs. Carl Spackler. We’re in the home stretch!

The moment has arrived when we can begin to tackle the Caddyshack semiosphere’s fourth and final code. (Topographically speaking, I’m referring to the top-right and bottom-left vertices of the Caddyshack meaning map which I’ve evolved over the course of the series thus far. These are the two blank areas in the meaning map depicted by Fig. 7.) Roland Barthes describes any code associated with these particular vertices as a semiosphere’s “hermeneutic” code. What he means is that every semiosphere is troubled and subverted from within by a code whose paradigms raise doubts about the master code and its supporting codes.

Let me explain using the Caddyshack semiosphere, as I’ve limned it, as an illustration. As Fig. 7 demonstrates, the top-right and bottom-left vertices of our G-Schema are the furthest points, topographically, from the positions — the paradigms Golf Club and Caddy Shack — staked out by our meaning map’s master code (i.e., Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack). What does this indicate? The paradigmatic figures occupying our meaning map’s top-right and bottom-left vertices call into question the very notion that we are required to choose sides between the dominant discourse and its counter-discourse. The hermeneutic code, like Bartleby the Scrivener, reveals a disruptive truth that the dominant discourse and counter-discourse alike conceal: If one prefers not to choose between these options, then one does not have to!

A semiosphere’s hermeneutic code is a tricky thing to identify. As we’ll see, in this post and the next, it’s composed of an “antiheroic” paradigm (at top right, in a G-Schema) and an “anti-antiheroic” paradigm (bottom left). While it’s usually not too difficult to identify a cultural semiosphere’s antihero, when it comes to the world of brand positioning, it’s much trickier. The anti-antiheroic paradigm, meanwhile, is always a mystery, at least right up until we’ve arrived at our current stage of analysis. The literary theorist Fredric Jameson, a fierce proponent of the semiotic square, describes what I’m calling the anti-antiheroic paradigm as “a cipher or enigma for the mind,” and advises meaning-mappers to leave it for last. This is exactly what SEMIOVOX’s methodology does — leaves it for last.

By beginning with a semiosphere’s master code, then identifying the master code’s two supporting codes, as I’ve done with Caddyshack, we put ourselves in a position to employ abductive reasoning in this final stage. “Abduction,” as the pioneering American semiotician and logician Charles Sanders Peirce was the first to note, is a mode of inference that allows us to explain the unknown cause of those facts which induction (i.e., the scientific method) has permitted us to establish beyond reasonable doubt. In the case of our Caddyshack meaning map, the question is: What paradigms create the gaps that we can at this point perceive at top-right and bottom-left? Which Caddyshack figures resist choosing sides between Golf Club and Caddy Shack — and in so doing, call the movie’s premise into question?

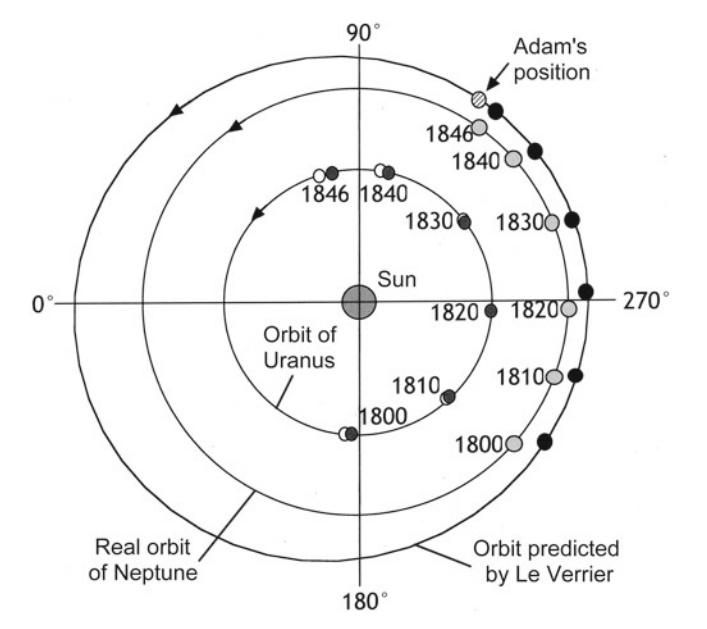

A classic scientific example of the use of abductive reasoning to infer the unknown cause of unexplainable facts is the discovery of Neptune. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was discovered that the orbit of Uranus, the outermost planet in our solar system known at the time, departed from the orbit as predicted by astronomers on the basis of Newton’s theory of universal gravitation and the auxiliary assumption that there were no further planets in the solar system. Astronomers John Couch Adams and Urbain Leverrier independently suggested that there was an eighth, undiscovered planet in the solar system — and it was this planet, which the world’s finest telescopes could not perceive, that provided the best possible explanation of Uranus’s deviating orbit. SEMIOVOX’s unique methodology is designed to make it possible for us to infer, abductively, the nature of a semiosphere’s otherwise undetectable hermeneutic code!

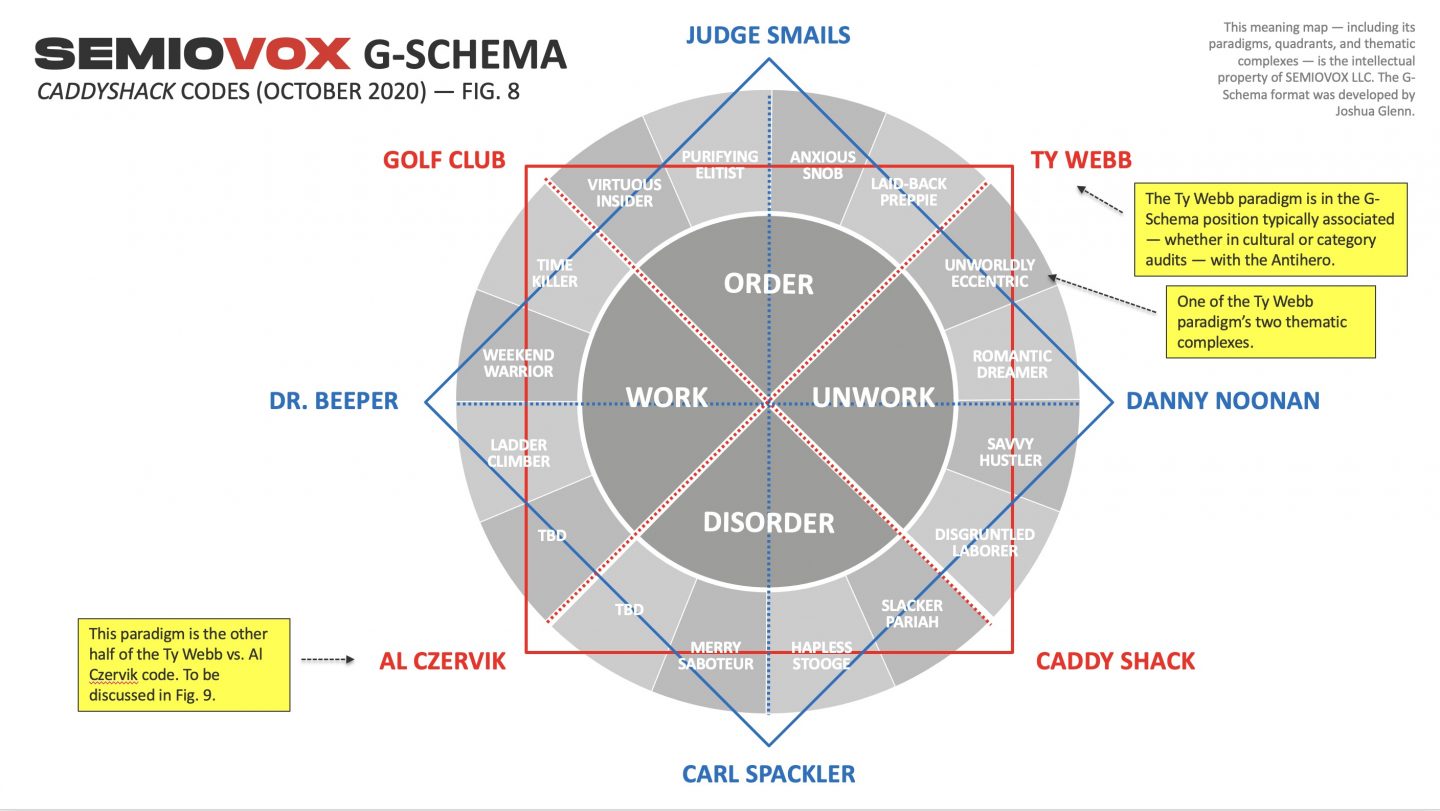

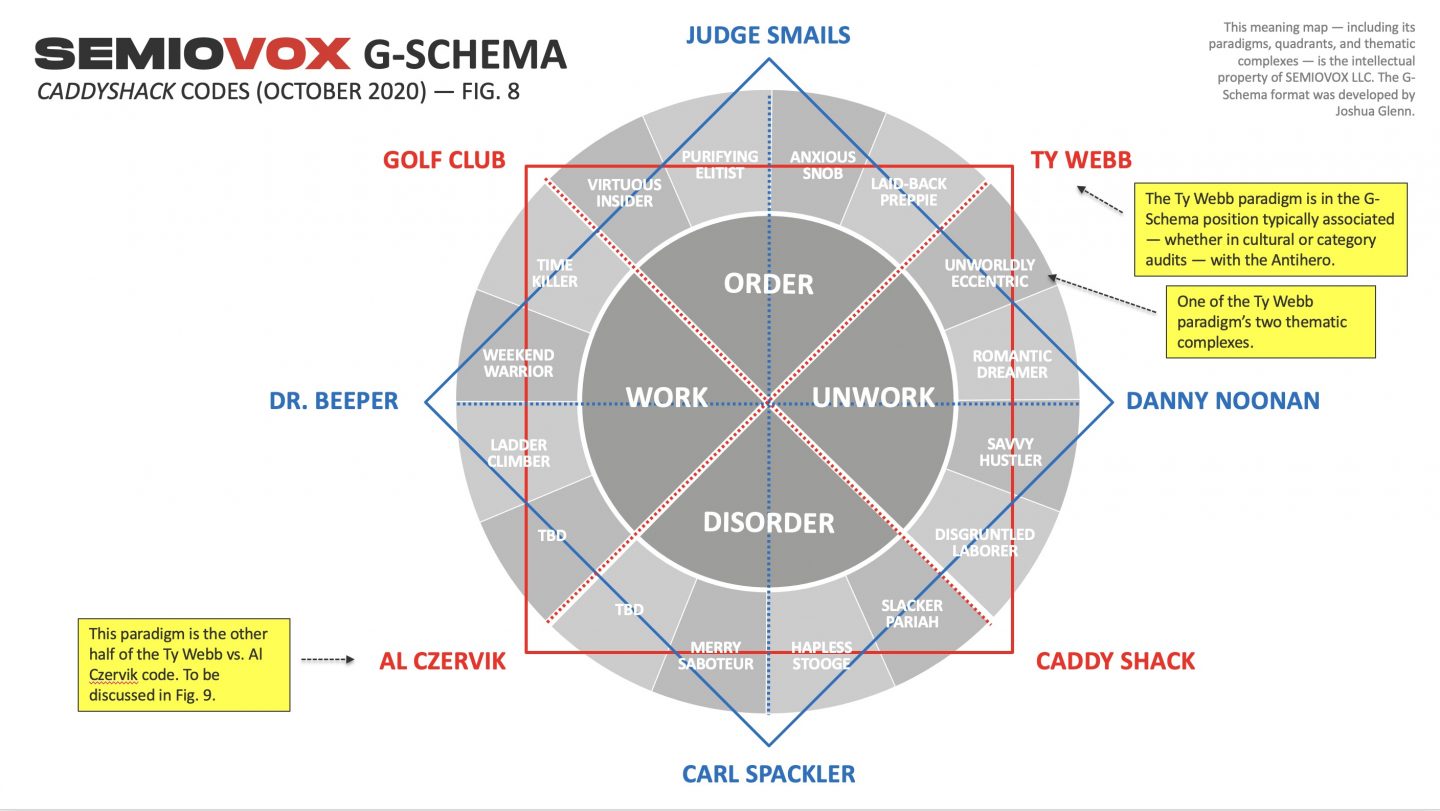

Voilà. As Fig. 8 (above) indicates, the Caddyshack semiosphere’s fourth, hermeneutic code is: Ty Webb vs. Al Czervik. The paradigm Ty Webb occupies the map’s top-right position. Ty Webb (played perfectly by Chevy Chase, for whom the role was more or less written) is the movie’s antihero; we’ll explore what that means in the current post. As for the paradigm Al Czervik, the movie’s anti-antihero, we’ll cover that in the series’ final post.

Paradigm

As depicted in Fig. 8, my analysis suggests that the paradigm Ty Webb’s two contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes can be described as follows: Laid-Back Preppie and Unworldly Eccentric. Within the Caddyshack semiosphere, specifically, these qualities are antiheroic.

An antihero rejects the values of the semiosphere’s dominant discourse (in this case, the paradigm Golf Club), but not entirely. If he or she were to reject the dominant discourse entirely, then they’d be aligned with the counter-discourse (in this case, paradigm Caddy Shack). In fact, the antihero also rejects the values of the semiosphere’s counter-discourse. Again, however, not entirely. If he or she were to reject the counter-discourse entirely, then they’d be aligned with the dominant discourse. The antihero opts not to align him- or herself with either the Establishment or the Counterculture, the Townspeople or the Bandits, the Empire or the Rebellion. Structurally speaking, they’re a frustrating figure. Are they cynical? Blasé? Indecisive? Self-destructive? Too wised-up for their own good? Wounded? Yes. They are, literally and figuratively, ambivalent.

The novel reader, comic-book fan, or moviegoer longs for the antihero to be recuperated by the “good guys.” (Most often, that means the counterculture; however, if you’re a reactionary who believes that the counterculture has triumphed, say, then the “good guys” might look like Establishment figures.) Middlebrow cultural productions, like Star Wars for example, will give us what we want: The cynical mercenary will, in the end, join with the rebels. Highbrow, lowbrow, or — in the case of Caddyshack — nobrow cultural productions refuse to give us satisfaction. The antihero isn’t recuperated. They remain cynical, wounded, blasé, indecisive, etc., etc., to the bitter end.

Is the antihero an admirable figure, then? Well, we often admire the antihero for being wised-up, for refusing the “either/or “choice offered to him or her by the semiosphere, for instead insisting on “both/and.” Like the id itself, of which the antihero is an avatar of sorts, they want it all. He or she doesn’t accept the necessity of choosing between alternatives, much less compromising, finding a “third way,” arriving at a tidy dialectical synthesis. The antihero is pulled in opposite directions; perversely, they enjoy it.

Adapting the terminology of C.S. Peirce’s existential graphs — a c. 1903 diagrammatic system to represent “the fundamental operations of reasoning” — we’d describe the Ty Webb categorical proposition like so: “It is not the case that Golf Club is Caddy Shack.” Despite the fact, then, that Ty Webb mediates between Golf Club and Caddy Shack, his is a negative-dialectical position in which two extreme opposites are “held together” in dynamic tension. He is a funambulist, a rope stretched across an abyss — it’s entertaining to watch him teeter and totter. This is what the true antihero does — see-saw, swerve, vacillate, equivocate.

Let’s take a look at Ty Webb’s contrasting yet complementary paradigms, in order to understand in what sense he is ambivalent and perverse.

Laid-Back Preppie

As is depicted in Fig. 8, the Laid-Back Preppie thematic complex is adjacent to the Anxious Snob thematic complex. Like the Anxious Snob, the Laid-Back Preppie more or less accepts the customs and culture of his or her class, and takes his or her (inherited) social status for granted; unlike the Anxious Snob, however, the Laid-Back Preppie doesn’t demand that Old Money customs and culture be shown the proper respect. Ty Webb may spend his days golfing at Bushwood and his evenings at the clubhouse bar, but he’s a misfit there. He’s addicted to the lifestyle, but scorns it as well.

Despite his overdetermined preppie appearance throughout the movie, Ty demonstrates his disrespect for Bushwood at various points. At 37:59, for example, we find him urinating on the golf course (image above). And at 1:19:58, he pulls up in Czervik’s car directly onto the golf course, driving Smails into a frenzy. His transgressive behavior increases under the pressure of the money match, for example, when he invades Smails’s personal space by putting his arm chummily around his shoulders (1:23:30).

Ty’s ambivalent attitude is apparent from his first scene in Caddyshack. Our hero, Noonan, is pouring out his soul: “I’m going to end up working in a lumber yard for the rest of my life.” ”What’s wrong with lumber?” asks Ty, who is dressed like Jay Gatsby, down to his two-tone golf cleats, without any discernible snark or leg-pullery (4:45). “I own two lumber yards.” And at 38:25, when Danny asks whether he should go to college, Ty says no. From the start, we realize that although Ty may be a mentor of some kind to Danny, he will not be pulled into the Country Club vs. Caddy Shack struggle.

At various moments when Ty could prove himself a heroic caste rebel, he steadfastly refuses to do so. Finding himself inside Carl Spackler’s hovel, at 1:15:36, Ty is appalled at the squalor. “It’s really, uh, it’s really awful,” he tells Carl. When Carl laments that people say he’s stupid, Ty replies, “Oh, people don’t say that about you — as far as you know” (1:16:53). And in an often-quoted exchange, when Ty insincerely invites Carl over to his own house, and Carl eagerly accepts, asking whether there’s a swimming pool, Ty says, “We have a pond in the back. We have a pool and a pond. A pond would be good for you” (1:19:10). His honesty is bracing, and funny. But the antihero never budges from the neither/nor position he has staked out.

How did Ty, whose father helped build Bushwood, end up so scornful of its customs and culture? We’re offered a clue, perhaps, at 16:52–16:56 when Smails’s recalcitrant grandson Spaulding is informed, by the Judge, that “You’re playing golf and you’re going to like it!” Spaulding unwillingly heads into the locker room and, just as he vanishes, Ty magically appears; ambivalent young preppies become ambivalent grown-up preppies, maybe. It’s not that Spaulding, who is insensitive and stupid, has the making of an antiheroic figure; but we’re offered some insight into Ty’s warped soul.

Smails’s niece, Lacey Underall — who, like her cousin Spaulding, has no interest in spending her time at Bushwood — also offers a contrast to Ty. She too doesn’t rebel against her privilege, but disrespects Bushwood’s stuffy customs and boring pastimes. When Lacey gives Ty the eye at 33:50, he responds enthusiastically — an absurd jet of steam issues from his mouth and nose. But Lacey isn’t an antiheroic type. She’s far more invested in the way of life represented by Bushwood than she lets on. Her efforts to seduce Ty can be understood, then, as a kind of honeypot trap. She’s like Allison Williams’s character in Get Out, on the prowl for fresh talent to add some vitality to her enervated caste’s tired-out genetic stock.. If she end Ty up together, at the movie’s end, it will signal that he has been seduced back into the Golf Club paradigm. Like Han Solo, he’ll be an ex-antihero.

On the other hand, perhaps there is some hope for Lacey. At 44:59, when she shows off her figure and (diving) form to the awestruck caddies, and again at 53:39 when she checks out Danny Noonan despite that fact that her yacht club pals are snickering at him, we get the distinct impression that Lacey isn’t an anxious snob, nor is she a purifying elitist. Also, throughout her fling with Ty, we can’t help but admire how Lacey handles herself. She’s the coolest character in the movie. When Smails is trashing the bedroom with a golf club, Lacey doesn’t sweat it. She shrugs, as if to signal to Noonan, it’s all part of the game. When she swings, she hangs past right and wrong.

We read, in Nashawaty’s Caddyshack: The Making of a Hollywood Cinderella Story, that at the end of the May 1979 script that was supposed to be the movie’s final script, Ty Webb and Lacey Underall end up together. They do share one final meaningful glance, near the end of the money match. But it’s unclear what this glance portends. The bottom line is: Lacey should have had a more important role in Caddyshack. Let’s get back to Ty Webb.

As Fig. 8 indicates, the Laid-Back Preppie thematic complex is diametrically opposed to one of the paradigm Al Czervik’s complexes. One aspect of the paradigm Al Czervik, that is to say, is emphatically not laid-back and emphatically not preppie. So although the two characters end up on the same team during the money match, Webb and Czervik can never truly be allies. Their truly odd, awkward handshake at 1:09:55 (shown above), and another awkward handshake at 1:13:46, is a particularly inspired piece of blocking… it’s an illustration of the vexed relation between a semiosphere’s antihero and its anti-antihero. Although Ty and Al may both refuse to buy into the semiosphere’s master code, they are ice and fire; Webb is too cool for school, while Czervik comes on too strong. Neither of them fits in.

Unworldly Eccentric

“Doug Kenney had modeled Ty after himself,” we read in Chris Nashawaty’s Caddyshack book. “Or how he liked to imagine himself: someone who sails through life without a care and a fondness for quoting Zen philosophers…” The paradigm Ty Webb’s other thematic complex, Unworldly Eccentric, offers another angle via which to understand the character’s antiheroism.

At 6:15, a blindfolded Ty tells Danny that “there’s a force in the universe that makes things happen. All you have to do is get in touch with it. Stop thinking. Let things happen.” In a later scene (at 39:01), Ty says, “Don’t get obsessed with your desires, Danny. The Zen philosopher Basho once wrote, ‘A flute with no holes is not a flute’ — and a donut with no holes is a danish.” People always assume that Ty is attributing the donut joke to Basho, but I think the way that I’ve punctuated his pronunciamento is the correct way; that is to say, he can’t resist riffing on Basho’s wise koan. Asked by Czervik, at 1:12:33, if he’s “religious or something,” Ty answers honestly: “You might say that,” then awkwardly spills his drink. He’s a Zen clown, whose jokes and antics remind us that earnestness will get us nowhere.

Ty’s refusal to play golf against others, or even to keep score when he golfs, is a source of tremendous bafflement to Judge Smails. “How do you measure yourself with other golfers?” Smail demands to know (17:05). “By height,” Ty quips. At 1:12:17, when Czervik asks him to play in the money match with him, against Smails and Beeper, Ty doesn’t want to do it. “I don’t play golf for money… against people,” he awkwardly, bashfully explains. As discussed in previous posts, for Smails — and Bushwood generally — one’s low golf score serves as proof of one’s elect status. Which is why it’s so troubling, to Smails, that Ty Webb won’t reveal his own score. Does it mean that Webb is much more deserving than the others, ie., of his privileged status… or does it mean that Webb rejects Bushwood’s flawed ideology?

In the end, of course, Ty does play for money… against other people. He does so out of disgust for Smails and what Bushwood represents. But again, in doing so he’s not joining any rebellion. In fact, he’s completely unhinged by the experience. He begins to act “psychotically,” as Carl informs him. And during the match itself, he can barely hold it together. The unworldly eccentric has permitted himself to be drawn into the club’s petty squabbles; like the graceful albatross, in Baudelaire’s poem, whose powerful wings render him clumsy when he’s not in the air, Ty has now become buffoonish.

Something similar happens when Lacey beards Ty in his den. Although he’s obviously attracted to her, he’s incapable of being cool and above it all (like she is). His home — with its samurai swords, pizza boxes, and uncashed checks — is a cuckoo’s nest. Still, when Lacey says that he’s pathetic, he sticks up for himself: “To me there’s a subtle perfection to everything I do,” he says (50:15). “I have my own standards, my own way.” We see his own way a moment later, when instead of licking the salt, doing a tequila shot, then sucking a lemon, he snorts the salt, sucks the lemon, and throws the tequila over shoulder (51:03). “Will you get serious?” Lacey demands, as he massages her at 51:54. He will not. Instead, he accidentally dumps all the massage oil onto her back, then slides off onto the floor.

This thematic complex, too, gives us an intimation of the nature of one of the paradigm Al Czervik’s two complexes. While the antihero’s rejection of the semiosphere’s either/or (Golf Club vs. Caddy Shack) makes him an unworldly eccentric, the anti-antihero’s rejection will make him the opposite. What that entails, exactly, we’ll explore in the next installment.

There you have it: the first half of Ty Webb vs. Al Czervik, our Caddyshack meaning map’s hermeneutic code. I’ve identified the paradigm Ty Webb’s contrasting yet complementary thematic complexes, and brought these to life via a selection of source codes (“signs”) drawn from the movie. I’ve established not only what Ty Webb means — that is, what sense we Caddyshack viewers are encouraged to make of the character — but how this paradigm means what it means. To that end, I’ve surfaced many of the visual and verbal cues, from speech acts to facial expressions, clothing, mannerisms, etc., via which we are encouraged to construe what Ty Webb signifies not only within the movie, but also as an emblem of, you know, American Culture and Western Civilization c. 1980.

This series’ next installment will explore the second half of the Caddyshack semiosphere’s hermeneutic code: the paradigm Al Czervik.