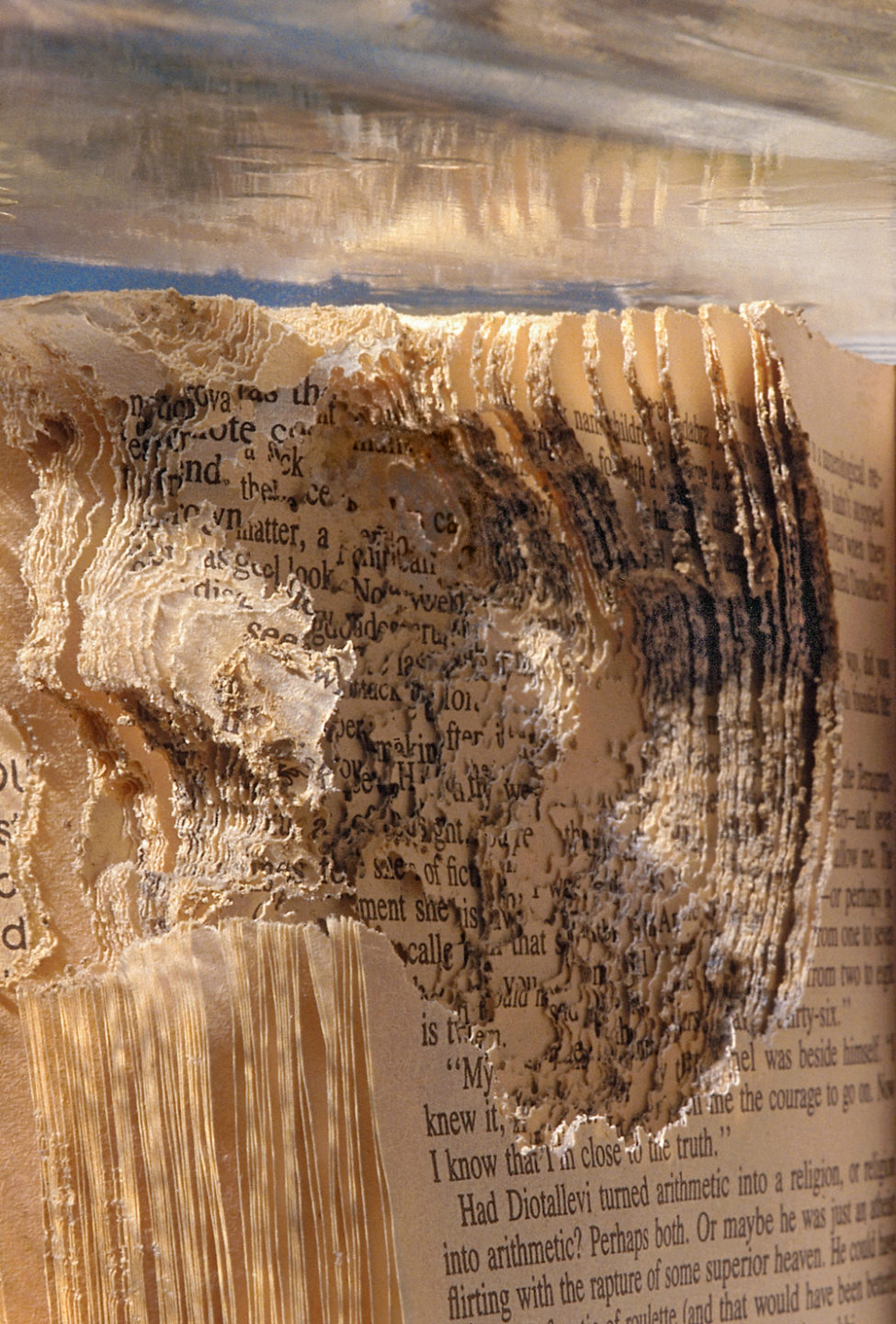

Photo: Rosamond Purcell

This article first appeared in The Boston Globe Magazine, on October 5, 2003.

In the summer of 1981, while en route to the Owls Head lighthouse, a tourist destination near Rockland, Maine, photographer Rosamond Purcell, then still several years away from becoming the renowned and even notorious artist she is today, stumbled upon an 11-acre junkyard owned and operated by a reticent local named William Buckminster.

“In heaps and mounds and prodigious hills the junk surged above us,” Purcell recounts in Owls Head (Quantuck Lane Press), a soon-to-be-published meditation on finding, keeping, and arranging things, and memoirs of the years the author spent obsessively returning to what she calls the “vastness, disorder, and gentle melancholy of the place.”

Beyond the glittering cliffs of industrial scrap metal that threatened to engulf Buckminster’s dilapidated antiques shop, Purcell discovered “the novelty of rural eccentricity and unfathomable chaos” itself: a field of silent outboard motors, a slope of harness and tractor hardware, an atoll of iron stoves, the cracked remains of what was reportedly once the largest pile of lobster buoys in the world, and tens of thousands of household items that had been crushed, bloated, bleached, and otherwise disfigured by time, rodents, and the elements.

Purcell writes that “a bemused Buckminster continued to sell me almost everything I wanted.” Becoming fiercely possessive of the Owls Head trash heap, Purcell excavated and purchased truckloads of “Maine-ified” detritus, ranging from petrified books and blackened rubber dolls to oxidized copper toilet floats and buckets of bowling trophies.

She transported the stuff to her home in Medford, where she took large-format Polaroids of the dreamlike collages she constructed from her treasures. Not merely a source of gorgeously damaged subject matter, the junkyard became the photographer’s muse: Her artwork from this period, as Purcell describes it today, examined “what happens between the ice and the inner tube … the rain and a road map.”

The Cambridge-born artist put her new archeological skills to the test by embarking on an evolving collaboration with the gadfly Harvard University paleontologist and science historian Stephen Jay Gould. With the grudging permission of curators, she photographed the all-but-forgotten stuffed animals, fossils, and skeletons crammed into the back rooms and locked drawers of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, the Smithsonian, and natural history museums across Europe. Illuminations: A Bestiary, the first of Purcell’s three collaborations with Gould, was published in 1986.

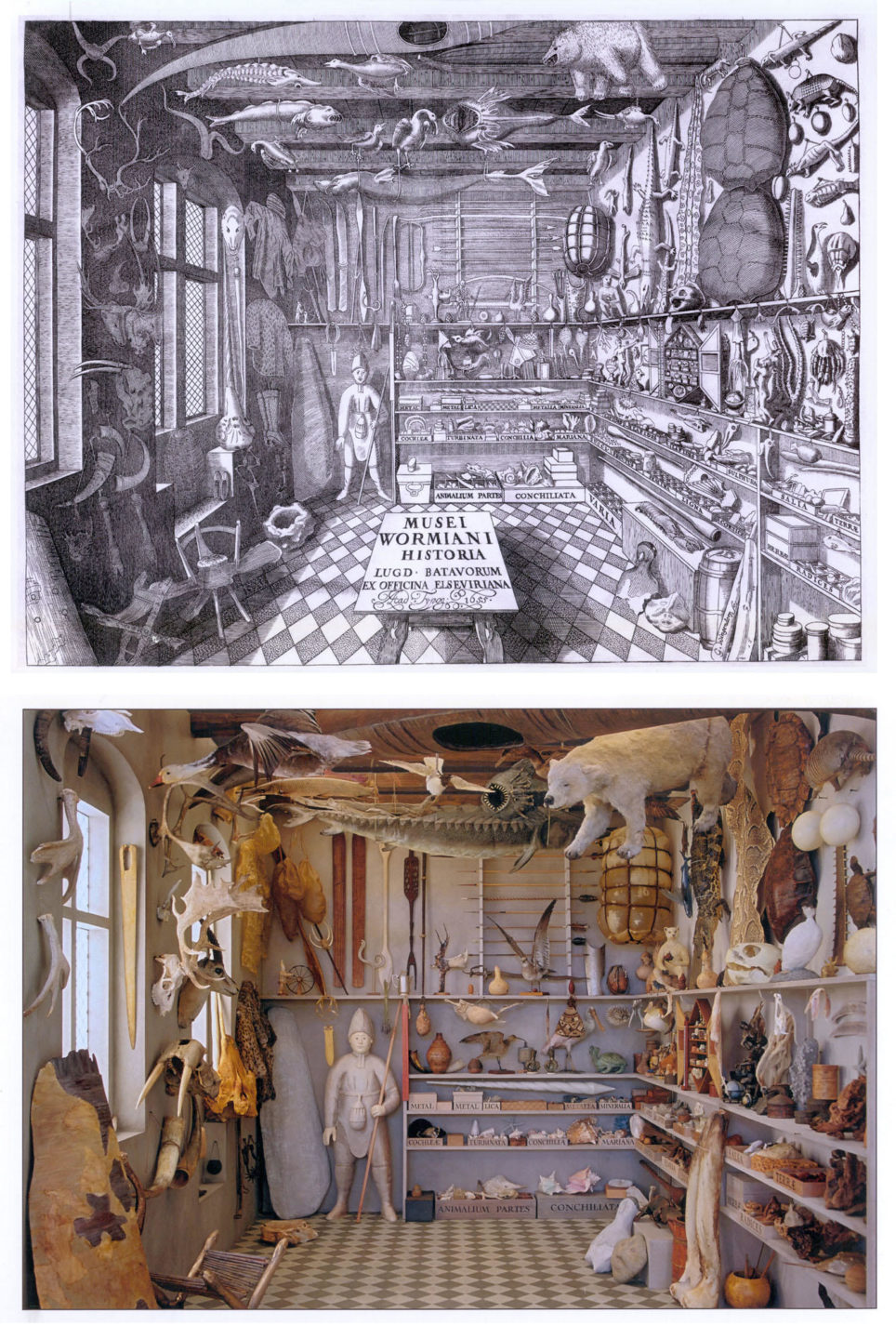

Somewhere along the way, Purcell learned about 17th-century Danish naturalist Olaus Worm, whose natural history collection, known today only through a 1655 engraving, is the most famous of the early modern Wunderkammern. These “wonder cabinets” were private museums whose specimens were arranged in a manner that appeared scientific but was in fact primarily theatrical. “To stun, more than to order or systematize, became the watchword of this enterprise,” as Gould was to explain.

Endlessly fascinated with the engraving of Worm’s collection, Purcell became increasingly impatient with modern taxonomic systems, which fail to group specimens aesthetically and intellectually in such a way as to invite viewers to participate in the enjoyable act of interpretation. “Part of the pleasure of viewing older collections,” she writes in the afterword to the book Finders, Keepers, “comes from not knowing exactly what to expect.”

In 1989, she was commissioned by the DeCordova Museum in Lincoln to install a series of ersatz wonder cabinets, using Owls Head finds as specimens, but this wasn’t enough.

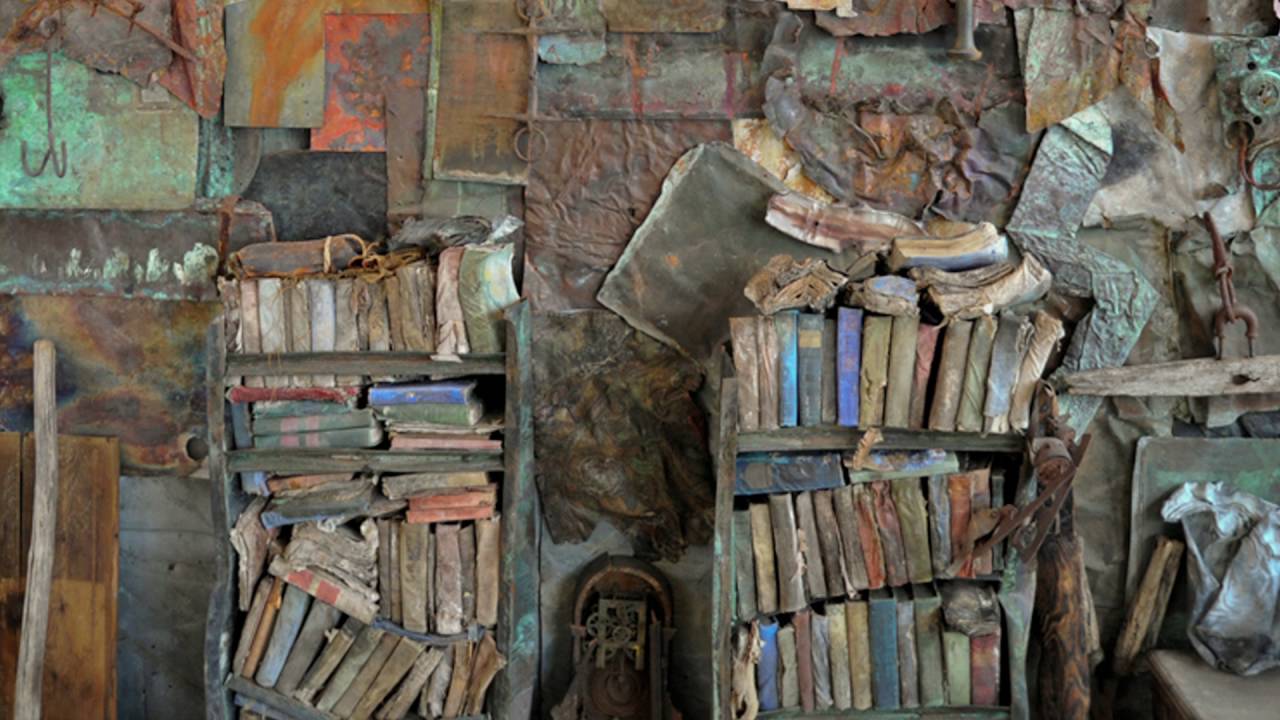

Shortly afterward, Purcell acquired a 1,000-square-foot studio at Brickbottom, a Somerville cannery that had been converted into an artists’ building, and proceeded to build an oddball natural history museum of her own. She nailed dozens of oxidized metal plates from a deconstructed tugboat onto the studio walls; organized innumerable decayed gewgaws into drawers, trunks, boxes, and cabinets; and solemnly ranged particularly exotic junkyard discoveries along open shelves and in glass display cases.

Purcell’s studio was eventually hailed as a theatrical sculpture in the assemblage tradition, in which one creates artworks out of objects never intended for that purpose. As Robert McCracken Peck, a curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, has noted, “Purcell’s careful placement and juxtaposition of these [junkyard] objects invoked from each an inexplicably powerful aura of significance — and mystery.”

Not long ago, Lisa Melandri, a former assistant and student of Purcell’s, arranged to have the studio’s contents shipped to the Santa Monica Museum of Art in California, where she is deputy director. For Melandri’s planned exhibition, Purcell begged and borrowed from curators around the country in order to construct a full-size facsimile of “Worm’s Room,” as she calls it. “Rosamond Purcell: Two Rooms,” featuring both her reconstructed studio and the Wunderkammer, opened in May; on Tuesday, it will begin a two-month run at Tufts University Gallery in Medford.

I’ve been an admirer of Purcell’s work since the 1995 publication of Suspended Animation, a collection of her photos — with accompanying essays by the pathologist F. Gonzalez Crussi — of preserved body parts. The book sounds gruesome, but Purcell’s warm, inquiring photographs of preserved fetuses and dismembered heads managed to transform my initially morbid curiosity into something like sympathy for life itself.

So, in August, curious about why Owls Head, a copy of which I’d just received, contained no photos (except for a handful modestly used as endnotes), I telephoned Purcell at home. “Those photos of Bucky and his place are incidental to my interest in the place itself,” she said, rather cryptically, before inviting me to meet her at Brickbottom.

Walking toward her studio a few days later, I tried to see the mangled, flaking metal parts stacked in front of the area’s body shops and the ornamental ironworks through Purcell’s eyes. I’d finished Owls Head and had soaked up some of the author’s passion for the “exquisite reductions and patinas” of all things warped and weathered, rotted and rusted.

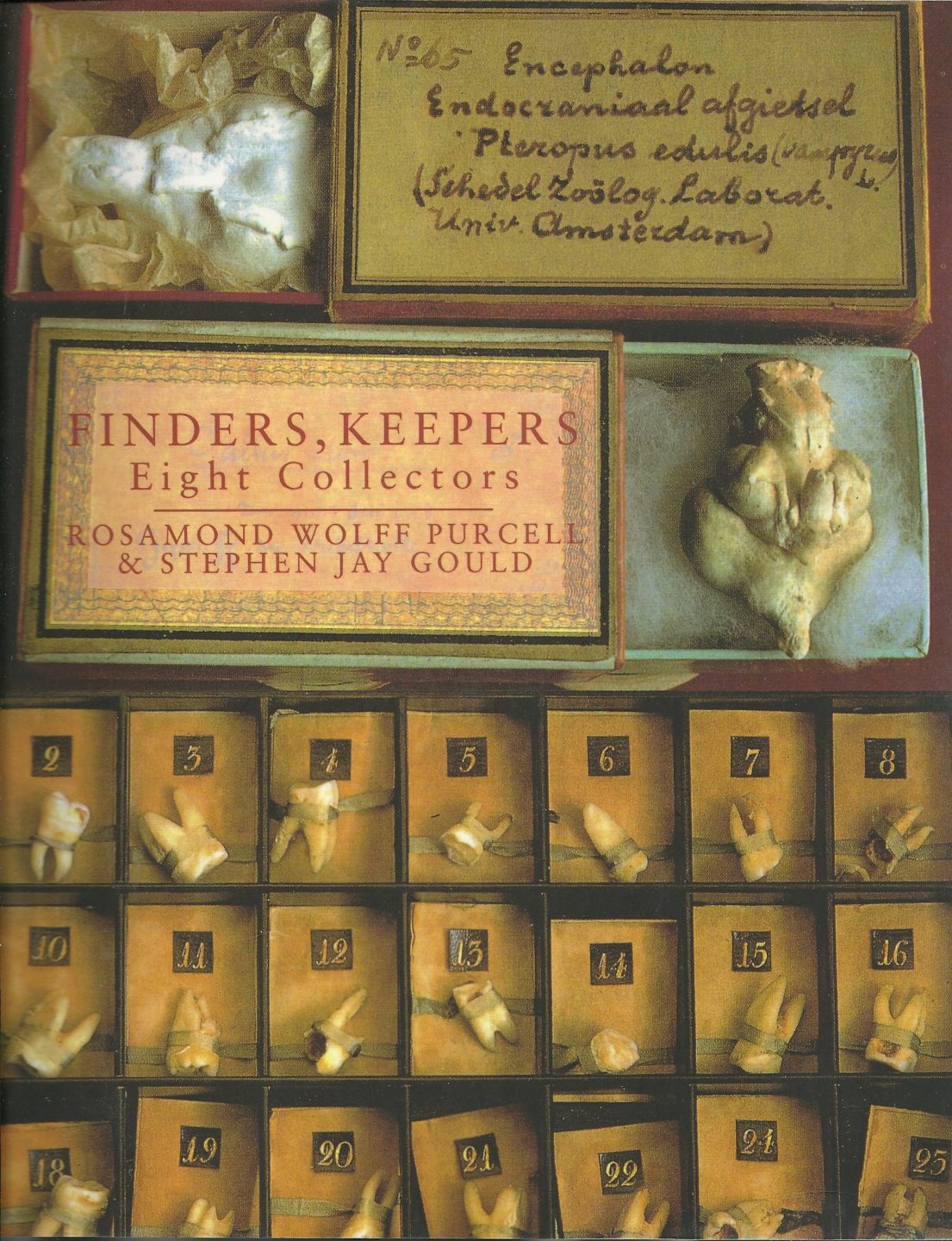

Among connoisseurs of the timeworn, the unlovely, and the uncanny, of course, Purcell is a pioneer. When Finders, Keepers, her second book with Gould, appeared in 1992, its photos of pickled children’s limbs and faces (discovered in an anatomical museum in Leiden, the Netherlands), not to mention human teeth pulled out of his subjects’ mouths by the Russian czar Peter the Great, shocked an appreciative public bored of its own unshockability.

During the 1990s, the mainstream appeal of what some critics dismissed as her “formaldehyde photography” helped make Purcell’s name synonymous with everything macabre and grotesque. In 1994, the Getty Research Institute, then located in Santa Monica, invited her to curate an exhibit of mythical monsters and “natural anomalies”: conjoined twins, the skeleton of a hydrocephalic child “whose skull has opened like a flower,” that sort of thing. Purcell was accused in some quarters of callously aestheticizing human pain and suffering, but Special Cases (1997), a solo book project based on the exhibit, was another popular success.

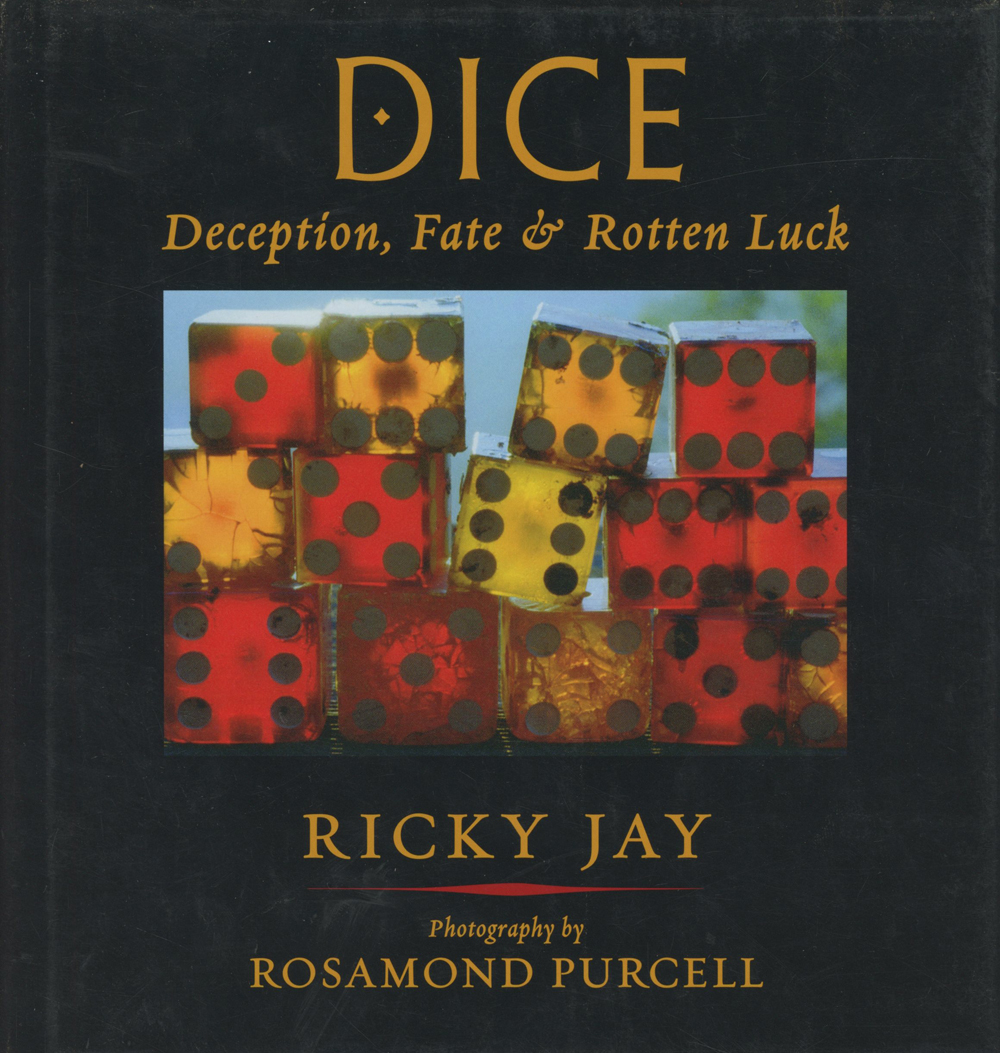

When Ricky Jay, the actor and sleight-of-hand artist, commissioned her to document his collection of crumbling dice for Dice: Deception, Fate & Rotten Luck (Quantuck Lane Press), published last winter, he dubbed Purcell the “doyenne of decaying objects.” The moniker makes her sound like a goth Martha Stewart or a copywriter for Abercrombie & Fitch, whose catalog asks one to choose between “river-dredged,” “gravel-ground,” and “jetty-tattered” shorts. This is unfortunate, because in the end, neither Purcell’s outre subject matter nor the artist’s obsession with “partially eroded or effaced surfaces” really explains the allure of her art.

If Illuminations and Finders, Keepers upset some of the collection managers involved (Purcell dedicated the former to “all my curator friends and foes”), it wasn’t because Purcell made their specimens look weird, but because she pointedly eschewed what she and Gould considered the pseudo-objectivity of traditional natural history photographic essays. By shooting specimens slightly out of scale and context, Purcell self-consciously transformed herself into an anti-curator, one who urged viewers to participate creatively in assigning meaning to life’s found objects — and to reconnect, through the imagination, with the natural world.

Her photographs, I decided as I reached the front steps of Brickbottom, will certainly outlast the current trend for “experienced” kitchenware and “pre-weathered” flight jackets. So why, I wondered again, did Purcell suddenly decide to write a book without photos? I had to know.

I was greeted outside the door to her studio by Purcell herself, an endearingly shy 61-year-old dressed in sandals, linen trousers, and a vest. She appeared reluctant, for reasons that soon became clear, to go inside without me.

“It’s the first time the contents of this place were ever moved. Eighty enormous cartons,” Purcell said distractedly as we entered. “I believe things should be kept in order, but the studio is disrupted now.”

At first, I wasn’t sure what she meant. Along one wall, heavy-duty shelves groaned with neatly stored artifacts: test tubes in a tangle of cardboard, a ruined kiddie pedal car. White shelves near the front door boasted mini-collections of tree roots, shattered clocks, cap-gun fragments. And from the kitchenette sprouted fantastical towers made of lamp stands, pedestals, stove parts, and stray architectural elements. To my eyes, the studio seemed anything but emptied out or disorganized.

Before long, though, a heavy wooden bracket fell on my hostess’s foot, and I decided that perhaps the place did look a bit like a schizophrenic’s hideaway. I mentioned this to Purcell, who pointed to a shiny shopping cart piled with refuse and joked, “I’m practicing for that eventuality.”

With an apologetic gesture toward a wall formerly covered with scrap metal and shelves of unreadable, rocklike books, she complained: “It’s just not the same now. I can’t stand being here.” She spends her time at home these days, she said, working not on photography but writing.

On that note, we sat down in a mismatched pair of easy chairs and talked about Owls Head. What was it about Buckminster’s place, I asked, that made her feel compelled to express herself through the medium of prose?

“Buckminster’s is a state of mind, and that’s more important to me than the literal details,” Purcell replied. “I wanted to articulate a philosophy of objects, and you just can’t show that in pictures.”

A state of mind? I asked. “After visiting Buckminster’s for years and years, I found myself constantly wondering, ‘What is this place all about?’ ” she said. “So I started using the junkyard to figure out things about the material world that bothered me.”

In fits and starts, and with many sidelong looks, as though she wasn’t sure I was taking her seriously, Purcell explained herself. “Questions about order, purpose, and meaning are so abstract,” she said, “but they became concrete, for me, at Buckminster’s.

“For years, I was simply excited by the way these self-similar American manufactured items had, at Owls Head, reached the outer limits of familiarity. They’d become unique and ripe for re-purposing. But eventually,” she continued, “I came to understand that each of these objects was only meaningful within a constellation of other objects.

“Once, when a visitor offered to buy a flattened tin can for $300, I refused,” Purcell recounted. “I had decided that each of the items in my studio are elements in a vast, profoundly disorganized system of meaning. I became afraid that I’d never get to the center of it — and that if I did get there, there wouldn’t be anything there. It was this anxiety that made me return to Buckminster’s, and that’s why I spent years arranging and rearranging everything in my studio.”

How did Buckminster figure into all this? I asked. “Bucky became a hero to me,” Purcell said. “His junkyard is so chaotic, but he was always so steady, so consistent. If he’d been erratic, I would have given up on the quest to figure out what it all means.”

So what does it all mean? “What I finally realized is that Buckminster’s is a microcosm of the universe itself, where a process of entropic dissolution is going on all the time,” Purcell said. “My studio, which replicates Buckminster’s, is a replica of a replica, and so are my efforts to place things in meaningful patterns. Bucky and I only understand fragments — any arrangement of them is arbitrary.”

And what’s at the center of this endlessly dissolving and reforming universe? “We all are,” said Purcell. “Buckminster’s never-ending labors to sustain, repair, and make sense of the world, while naturally contributing to further entropy, is an excellent way to exist, I think. He’s helped me realize that maintaining perfection is not possible.”

She continued: “Bucky once told me, ‘I live like a mole.’ It took me a long time to understand that a mole is a spelunker, not a thief; he’s just passing through, respectfully. I have never seen Buckminster treat anything like trash. He acts as though each object in his inventory appeared from out of nowhere and must be handled with care.”

Purcell stopped and looked straight at me. “Isn’t that a fine way to behave within the natural world?” she asked.

Our interview concluded, I asked Purcell whether she planned to continue excavating Buckminster’s. “I think my collecting days are over. And I don’t think I can put the studio back the way it was,” she said. “Maybe the project was to get this stuff from Bucky, set it up, take pictures of it, write about it, and then send it out on the road.”

A moment later, though, after demanding that I admire a rotted silk lampshade (“So perfectly dissolved!”) and a ship’s tiller that she’d acquired from Buckminster just a week earlier, Purcell changed her tune.

“If readers like Owls Head, I can stop collecting,” she said. “But if they don’t like the book, I may have to keep on doing all this.”