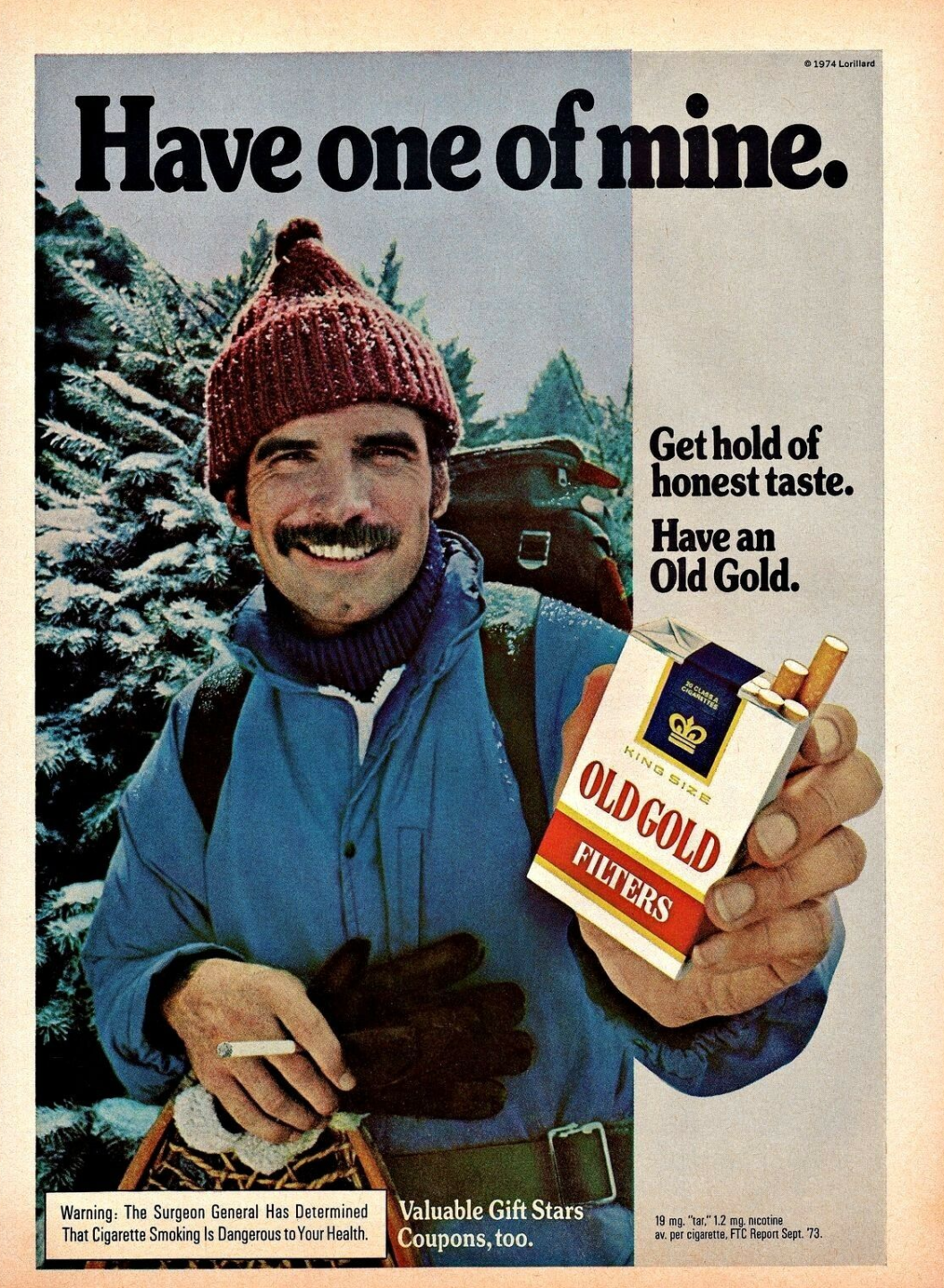

The year 1974 — according to my well-known periodization scheme — is the first year of the cultural era known as the Seventies (1974–1983). This ad offers a sneak peek at what then lay ahead for white heterosexual men.

Burt Reynolds — whose look this guy is going for — was the avatar of Seventies masculinity. He’d play the leading role in many box office hits from 1974–1983: The Longest Yard (1974), Smokey and the Bandit (1977), Semi-Tough (1977), The End (1978), Hooper (1978), Starting Over (1979), Smokey and the Bandit II (1980), The Cannonball Run (1981), Sharky’s Machine (1981), and The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982). In fact, during the second half of this period, he was the world’s number one box-office star for five consecutive years. Tough, sexy — yet somehow self-mocking, not taking any of this “macho” stuff too seriously — Reynolds demonstrated a way for post-Sixties men to have their cake and eat it too.

It was a tricky time, for white heterosexual men! As a result of the civil rights, women’s liberation, and gay rights movements, white heterosexual men were being called to account — beginning right around now — for their part in the oppression of white women, gay men, and nonwhite men and women. Also, at a time of growing unemployment and change in established industries (note: the economic woes of the era began in 1974), white men were forced to reconfigure their ideas of themselves. By the end of the era, a backlash would have begun; the angry white man — no longer depicted as a loser who has failed to keep up with the times, as in Joe, say, or Raging Bull, or All in the Family, or indeed Reynolds’s proto-Proud Boy character in his breakout movie, Deliverance — would have emerged, parroting talk-radio rhetoric about “reverse discrimination.” But at the beginning of the era, we had instead a self-aware, why-the-hell-not “New Macho” movement.

In “Psyching Out the New Macho,” a February 1975 feature in New York magazine, John Mariani noted the emergence of a different kind of macho man. The kind of guy who would hit on women in bars by denouncing the “old macho” attitude towards women. “What could be more macho?” demanded Mariani. “Macho has changed since the good old days, when it meant something like putting out a cigarette in your hand, to the new days, when it is more likely to mean emptying an ashtray;” or — as seen in the ad here — offering an “honest” cigarette as a token of his own integrity. With a smile that suggests he’s willing to play this game. As long as he can win at it.