The DECODER series — to which SEMIOVOX has invited our semiotician colleagues from around the world to contribute — explores fictional semiotician-esque action as depicted in books, movies, TV shows, etc.

In 1974, the far-out filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky recruited the bande dessinée artist Jean Giraud, then (and still today) known mostly for his gritty Western Fort Navajo/Blueberry comic artwork, to design the look and feel of his (alas, never-realized) adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune. That same year, Giraud co-founded Les Humanoïdes Associés, a collective that immediately began publishing Métal Hurlant.

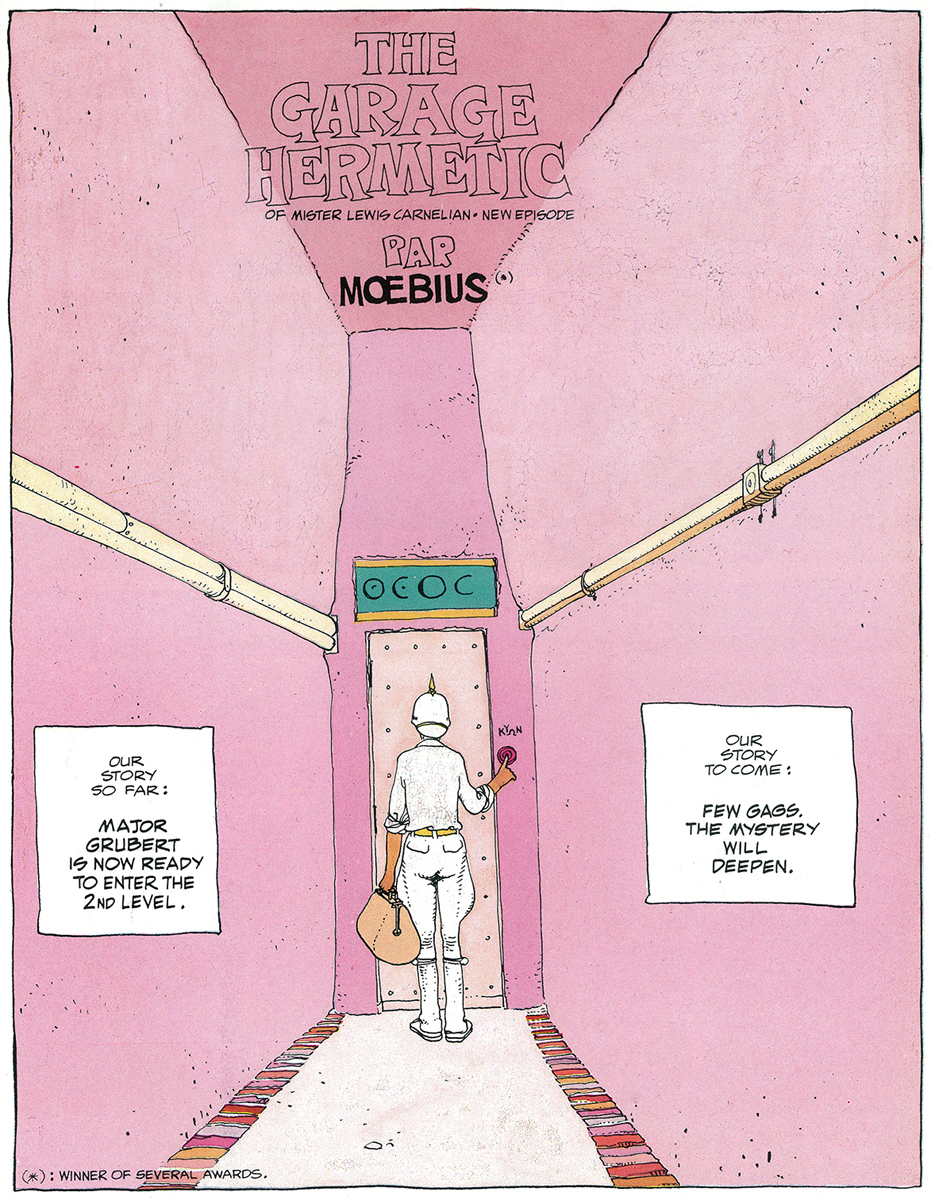

Under the non-orientable nom de plume Moebius, in the pages of this paradigm-shattering adult comics magazine, over the following decade or so Giraud would serialize several gorgeous, trippy, philosophical sci-fi/fantasy graphic novels. Though I’m a fan of the wordless Arzach stories (1974–1975) and of course L’Incal (1980–1985, written by Jodorowsky), my semiotician’s brain is particularly stimulated by Giraud’s Le Garage Hermétique (1976–1979).*

The story’s plot concerns the efforts of Lewis Carnelian (originally “Jerry Cornelius,” a dashing, meta-textual agent of entropy first introduced in the New Wave sci-fi of Michael Moorcock) to infiltrate the “levels” located within an asteroid known as Le Garage Hermétique; and also the efforts of Major Grubert, the sola topi-sporting, demiurge-ish creator of this pocket universe, to stymie him. Characters, biomes, a MacGuffin (a damaged “cable box”), and theories of what may really be going on here metastasize.

All of which provides Giraud with the opportunity to draw: robots, spaceships, mutants and aliens, desert landscapes, futuristic cities, steam trains, cowboys, explosions! The artwork’s style (which occasionally pays homage to pioneering American comics artists, from Lee Falk to Will Elder) transmogrifies from one installment, sometimes one panel, to the next: realistic vs. cartoonish, ultra-detailed vs. spare, dramatic vs. slapstick.

“I drew the first two pages with the feeling of making up a big joke, a complete mystery, something that could not possibly lead anywhere,” Giraud would explain. Persuaded by his editor at Métal Hurlant to transform this one-off inside joke into a world-building exercise, he was forced to scramble to establish continuity (connect the plot-dots) in imaginative, even absurdist ways. Making/finding meaning in a seat-of-the-pants way would become a feature, not a bug, of Le Garage Hermétique: “Soon I decided to experiment with the story telling itself, by challenging myself every month to solve the continuity problems that I had introduced in previous months.”

We might call a high-wire, self-gamified process of the sort Giraud describes “narrative kintsugi” — i.e., breaking, then making visible repairs to a story. As a result of which the reader is pulled in and pushed out, experiencing vicariously something of what the author of such a beautifully broken narrative undergoes in its creation.

“By creating this feeling of permanent insecurity,” Giraud would recall, “I was forced to experience [again and again] the total joy of creating a continuity.” My semio colleagues will empathize with this rarified state. In fact, C.S. Peirce once compared the feeling of having arrived successfully at a “hypothetic inference” (i.e., connecting the dots) with the “peculiar musical emotion” that an audiophile may experience when hearing an orchestra’s various instruments achieve harmony. The continuity-joy experienced by sensitive semioticians is equally peculiar and emotional.

A word of caution. For those of us for whom continuity-joy releases endorphins, Le Garage Hermétique, which concludes (as the author puts it) “on yet another open-ended sequence, which introduces a potentially unlimited incoherence factor,” may be habit-forming.

* I hesitate to translate the title of Giraud’s comic since the French hermétique suggests not only “air-tight” (i.e., as befits a hollow asteroid within which life is sustained), but also the uncanny occult notion that our reality may not be what it seems.

DECODER: Adelina Vaca (Mexico) on ARRIVAL | William Liu (China) on A.I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE | Tim Spencer (England) on VURT | Ramona Lyons (USA) on BABEL-17 | Rachel Lawes (England) on NICE WORK | Alfredo Troncoso (Mexico) on THE ODYSSEY | Gabriela Pedranti (Spain) on MUSIC BOX | Charles Leech (Canada) on PATTERN RECOGNITION | Lucia Laurent-Neva (England) on LESSONS IN CHEMISTRY | Whitney Dunlap-Fowler (USA) on THE GIVER | Colette Sensier (England / Portugal) on PRIESTDADDY | Jamin Pelkey (Canada) on THE WONDER | Maciej Biedziński (Poland) on KOSMOS | Josh Glenn (USA) on LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE | Antje Weißenborn (Germany) on BABYLON BERLIN | Ximena Tobi (Argentina) on SIX FEET UNDER | Mariane Cara (Brazil) on ROPE | Maria Papanthymou (Greece) on MY FAMILY AND OTHER ANIMALS | Chirag Mediratta (India) on BLEACH | Dimitar Trendafilov (Bulgaria) on THE MATRIX | Martha Arango (Sweden) on ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE | Becks Collins (England) on THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY | Ivan Islas (Mexico) on THE NAME OF THE ROSE | Paulina Goch-Kenawy (Poland) on THE SENSE OF AN ENDING | Eugene Gorny (Thailand) on SHUTTER ISLAND & FRACTURED.

Also see these global semio series: COVID CODES | SEMIO OBJECTS | MAKING SENSE | COLOR CODEX | DECODER | CASE FILE | PHOTO OP | MEDIA DIET.