Slum Pandemic

Villa 31, Buenos Aires. Shared via Flickr with a creative commons license. Photo by Anita Gould.

The CASE FILE series — to which SEMIOVOX has invited our semiotician colleagues from around the world to contribute — shares memorable case studies via story telling.

In June 2020, a few months after the WHO had declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, Ximena Díaz Alarcón — an old friend and professional colleague — invited me to participate in a project studying the impact of the emergency lock-down on adolescents. The project had been commissioned by a well-known Argentinean NGO dedicated to children and technology. When I agreed to take part in this effort, I couldn’t imagine the ongoing impact doing so would have for me.

I was tasked with conducting telephone interviews, and moderating a WhatsApp group, with 12 teenagers living in poor neighbourhoods in Buenos Aires. Doing phone interviews with teenagers isn’t easy! It was essential that the conversation flowed like a casual chat. I had to be very expressive, use local slang, and try to generate a good emotional connection that would last at least 30 minutes. Some of the teens were reserved; others were talkative. As pieced the interviews together, I found myself telling a story that few Argentinians know: What it’s like to grow up in the slums here.

The project team’s initial hypothesis was that what teenagers regretted most about lock-down was not being able to see their friends. However, this idea hardly appeared in my interviewees’ accounts. Instead, they repeated over and over, they were enjoying spending so much time with their parents. Doing so was unusual for them, since their parents normally left for work very early and returned home very late.

Another hypothesis was that it must be more difficult for adolescents from the lower classes than for those from the middle classes to be at home all day long, due to the lack of their own personal space — considering that they live in small houses where several members of the family share the same room. What my interviews revealed was that because these teens had never had a space of their own, they didn’t miss it.

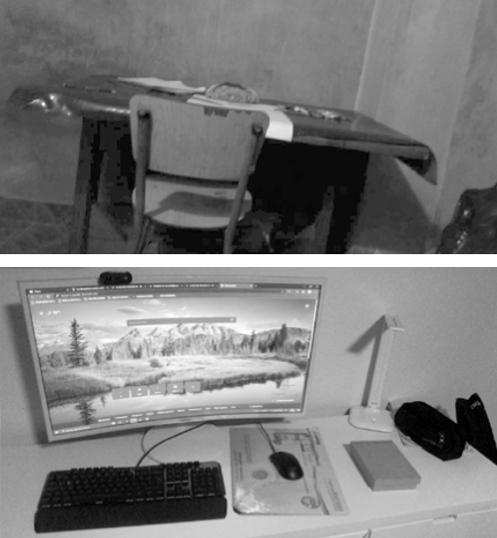

One by one, each of our hypotheses — which were biased by the figure of a middle-class adolescent — were disproven. We discovered a world that should not exist: a world in which, for example, in order to do schoolwork shared by teachers during a year-and-a-half lockdown, four siblings had to share a single cell phone.

My final report was integrated with another report — one that analyzed interviews with 12 adolescents from middle- and upper-middle-class communities. We’d always known in theory that there’s a deep gap between the opportunities afforded to poor young people and those afforded to young people from more well-off families. But our stories and photos provided evidence of this gap. I was devastated by this analysis.

As always, as soon as one report is completed and presented, we move on to the next. This time, however, I couldn’t move on so easily. I could not get the stories of these teenagers out of my head; I found it hard to naturalize the adverse reality I had witnessed firsthand. Several teens had mentioned to me an NGO they visited because it had a community dining room and recreational workshops. I went to the NGO’s website and found a volunteer form; for a few weeks, I looked at the form without completing it. Finally, I submitted the form and — in November 2020 — for the first time I paid a visit to the neighborhood I’d been studying. I’ve been volunteering there ever since, organizing vocational training courses and teaching school support classes.

There was another world just 30 minutes away from my home — but light-years away in terms of access and opportunities. For me, this research project opened a portal.

CASE FILE: Sónia Marques (Portugal) on BIRTHDAY CAKE | Malcolm Evans (Wales) on PET FOOD | Charles Leech (Canada) on HAGIOGRAPHY | Becks Collins (England) on LUXURY WATER | Alfredo Troncoso (Mexico) on LESS IS MORE | Stefania Gogna (Italy) on POST-ANGEL | Mariane Cara (Brazil) on MOTHER-PACKS | Whitney Dunlap-Fowler (USA) on WHERE THE BOYS ARE | Antje Weißenborn (Germany) on KITSCH | Chirag Mediratta (India) on “I WATCH, THEREFORE I AM” | Eugene Gorny (Thailand) on UNDEAD LUXURY | Adelina Vaca (Mexico) on CUBAN WAYS OF SEEING | Lucia Laurent-Neva (England) on DOLPHIN SQUARE | William Liu (China) on SCENT FANTASY | Clio Meurer (Brazil) on CHOCOLATE IDEOLOGY | Samuel Grange (France) on SWAZILAND CONDOMS | Serdar Paktin (Turkey/England) on KÜTUR KÜTUR | Ximena Tobi (Argentina) on SLUM PANDEMIC | Maciej Biedziński (Poland) on YOUTH LEISURE | Josh Glenn (USA) on THE AMERICAN SPIRIT | Martha Arango (Sweden) on M | Chris Arning (England) on X | Peter Glassen (Sweden) on WHEN SHABBY ISN’T CHIC | Joël Lim Du Bois (Malaysia) on RECONSTRUCTION SET | Ramona Lyons (USA) on THE FALL.

Also see these international semio series: COVID CODES | SEMIO OBJECTS | MAKING SENSE | COLOR CODEX | DECODER | CASE FILE