Laszlo

This is the second of eight installments in the series CASABLANCA CODES. See also the 2020 series CADDYSHACK CODES.

In this series’ previous installment, FERRARI was identified as the Casablanca semiosphere’s dominant-discourse paradigm. The paradigm FERRARI, that is to say, “governs” not only the thematic complex BLACK MARKETEER (in the semiosphere’s WAR territory), but also the thematic complex CRIME BOSS (in the BUSINESS territory). From this position, Signor Ferrari sanctions (officially approves) socioculturally legitimate feelings and actions, and as necessary imposes sanctions (disciplines, punishes) when the rules are transgressed.

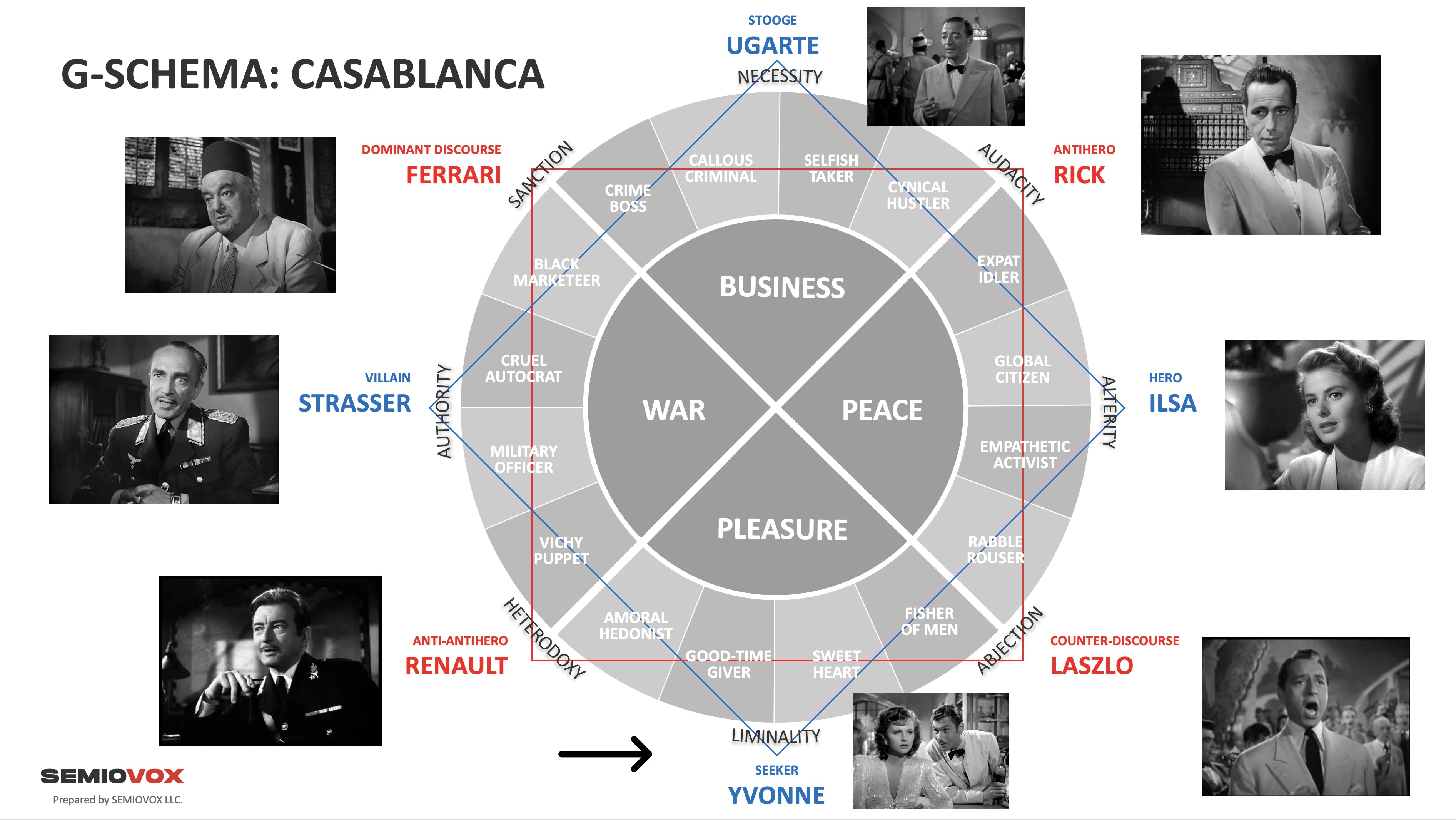

All of which is charted out via the Casablanca G-schema reproduced here:

In the entirely corrupt version of the city Casablanca depicted in this movie, Ferrari’s rules, and the feelings and actions Ferrari considers legitimate, are driven by “instrumental reason” — which, as Adorno and Horkheimer will tell us, concerns itself entirely with the efficiency with which goals (in this case, criminal and black-market goals) are achieved, and not at all with questions of right and wrong, or any meaning or purpose above and beyond these goals.

In any semiosphere, the dominant discourse is always threatened by a countervailing force that the semiotician Julia Kristeva describes, in 1980’s Powers of Horror, as abjection. “[A semiosphere’s dominant ] discourse,” she persuasively argues, “will seem tenable only if it ceaselessly confronts [its own] otherness, a burden both repellent and repelled… the abject.” In the G-schema-oriented semiotician’s methodology, therefore, once we’ve surfaced and dimensionalized a semiosphere’s dominant-discourse paradigm, we turn our attention to doing the same work around its counter-discourse paradigm.

If the dominant-discourse paradigm of the Casablanca semiosphere governs both the thematic complex BLACK MARKETEER (in the semiosphere’s WAR territory) and the thematic complex CRIME BOSS (in the BUSINESS territory), then what paradigm — also necessarily a “hybrid,” i.e., positioned across two territories — governs complexes in the opposing territories PEACE and PLEASURE? What paradigm represents moral (vs. instrumental) reason?

Victor Laszlo is the Czechoslovakian leader of a successful, pan-European anti-Nazi resistance movement. He’s been reported dead several times, and has escaped captivity more than once — including from a concentration camp. Now he’s turned up in Casablanca, from which jumping-off point he hopes to smuggle himself and his wife, Ilsa Lund, to the United States… where he’ll continue his courageous, outspoken mission.

If FERRARI is the Casablanca semiosphere’s “value,” then its “disvalue,” which is to say the semiosphere’s counter-discourse paradigm, is: LASZLO.

By the way: Semioticians often speak of “unmarked” and “marked” terms within a semiosphere. The former are related to the dominant discourse, an ideology rendered (as Roland Barthes would put it) natural, inevitable, and permanent, all of which is to say: “unmarked.” Markedness, by contrast, is the state of standing out as nontypical or divergent.

In Casablanca, Victor Laszlo — physically and morally upright, fearless and outspoken — stands out strikingly amongst Casablanca’s slouching and cynical, whispering and muttering, slinking and sneaking denizens. And as if any further textual evidence were needed, Laszlo is marked, quite literally, by a facial scar — a red badge of courage, proof positive of the heroic life he’s led up to this point. And he’s injured during the course of the movie, as well.

Both figuratively and literally, Victor Laszlo is a marked man.

The plot of Casablanca doesn’t pit Ferrari directly against Laszlo. Signor Ferrari is far too canny a character ever to admit how he feels about Laszlo; in fact, if anything, Ferrari appears to be moved by Lazlo’s and Ilsa’s plight. (He isn’t.) However, our structural analysis of Casablanca reveals that Laszlo must inevitably pose a problem for Ferrari… who profits, after all, from business and war.

Just look at how Laszlo gets Rick’s illegal casino closed down, on the Gestapo’s orders, despite Rick’s long-time bribery of Casablanca’s Vichy officials. Laszlo is a fly, if you will, in this semiosphere’s ointment… and we already know how brutally and precisely Ferrari deals with flies.

PS: It’s perhaps worth mentioning, at this juncture, a minor character from the 1966–71 gothic soap opera Dark Shadows, who perhaps could be said to embody both Ferrari’s criminality and Laszlo’s fortitude. A loyal servant of Angelique Collins (in the show’s 1840 flashback episodes), this character’s name is… Laszlo Ferrari.

Structurally speaking, LASZLO represents for FERRARI what Kristeva calls “a burden both repellent and repelled.” In order to maintain the tenability of the dominant discourse in this semiosphere, FERRARI must confront LASZLO. Yet the character Ferrari is a master chess-player… so he won’t do anything so straightforward as having Laszo killed, or even helping him on his way to safety. As discussed in this series’ previous installment, Ferrari instead strategizes brilliantly a means to use Laszlo, like a chess piece, in his “game” versus Rick (for control of the casino).

What thematic complexes, in the Casablanca semiosphere, are “governed” by the paradigm LASZLO? The complex that opposes — diametrically, in a structural sense — BLACK MARKETEER (in the WAR territory) is RABBLE ROUSER (in the PEACE territory); and the complex that diametrically opposes CRIME BOSS (in the BUSINESS territory) is FISHER OF MEN (in the PLEASURE territory). We’ll explore these complexes in depth, below. Let’s pause, first, though, for a few notes about the actor who portrays Victor Laszlo in Casablanca.

Paul Henreid was an Austrian Jew (on his father’s side), who by the time that Germany took over Austria in 1938 had become fervently anti-Nazi. After helping a Jewish comedian flee Germany, Henreid was designated an “official enemy of the Third Reich.” He moved to England, from which he was nearly deported as an enemy alien before the expat German actor Conrad Veidt, a staunch philosemite who’d been blacklisted and placed under house arrest by Joseph Goebbels (and who’d play the villainous Strasser in Casablanca) vouched for him.

Henreid is best remembered for Casablanca and other WWII-era roles, including the Gestapo officer Karl Marsen in Night Train to Munich (1940) and Jerry Durrance in Now, Voyager (1942). After the war, Henreid would be blacklisted by Hollywood studios for his opposition to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. He was as courageously outspoken in real life, it seems, as his character Laszlo is in Casablanca.

RABBLE ROUSER

The RABBLE ROUSER thematic complex is diametrically opposed, in our Casablanca G-Schema, to the BLACK MARKETEER complex.

As demonstrated in this series’ previous installment, this semiosphere’s BLACK MARKETEER involves not just any illicit activities, but specifically those that involve profiting through the subversion, evasion, and defiance of Vichy France’s (and the Gestapo’s) wartime rules and regulations. Whatever else Ferrari’s black-market activities may involve, they involve people-smuggling and related crimes (e.g., forging documents for that purpose). Rick, who has grown wealthy thanks to his night club’s illicit casino, draws the line at black market activities: “I don’t buy or sell people,” he insists. Ferrari, however, insists that’s what the black market is about.

Laszlo, in stark contrast to Ferrari, is an escape artist — and he’s in the business of setting people free. He, too, subverts, evades, and defies the fascists’ wartime rules and regulations… for idealistic reasons, though, instead of for profit. He’s earned a reputation as a freedom fighter, an intellectual engagé whose writings — and whose work as a strategist helping to unify, inspire, and even organize underground resistance networks across Europe — have made him one of the Third Reich’s most feared and hated enemies. He’s an inspiration.*

* Note the juxtaposition, on our G-schema, of the thematic complexes RABBLE ROUSER and EMPATHETIC ACTIVIST. As we’ll explore in the ILSA installment of this series, it’s Laszlo’s thinking and writing that inspired an impressionable young Ilsa to fall in love with him.

If FERRARI is this semiosphere’s superego (see the previous installment), then LASZLO is its anti-superego.* Laszlo’s presence in Casablanca threatens to subvert, undermine, and destroy the legitimacy of the dominant discourse — in which profit is the only reason to do anything — promulgated by Ferrari. While Ferrari would have us believe that Casablanca’s amoral, criminal, libertarian world is simply the way things have to be, Laszlo is a change agent who demands that we rethink “common sense,” because — or so he courageously insists — another world is possible. Even cynics like Rick and Renault are moved.

* “To each ego its object, to each superego its abject.” — Julia Kristeva

Rick, the former anti-fascist arms dealer (in pre-WWII conflicts) who in recent years has maintained an attitude of stoic cynicism regarding the Nazis, begins to emerge from his self-pitying daze at this point.

RENAULT: There is a man who’s arrived in Casablanca on his way to America. He will offer a fortune to anyone who will furnish him with an exit visa.

RICK: Yeah? What’s his name?

RENAULT: Victor Laszlo.

RICK: Victor Laszlo?

RENAULT: Rick, that is the first time I have ever seen you so impressed.

RICK: Well, he’s succeeded in impressing half the world.

Renault, too, is impressed. When Major Strasser complains that “Victor Laszlo published the foulest lies in the Prague newspapers until the very day we marched in, and even after that he continued to print scandal sheets in a cellar,” Renault responds: “Of course, one must admit he has great courage.”

Laszlo’s arrival in Casablanca is inspiring and galvanizing for the city’s anti-fascist underground. He is an avatar of this semiosphere’s PEACE territory — but this is not to say that he’s a pacifist. He is involved in every sort of anti-war effort, including violent resistance to the Nazis. When he first shows up at the Café Americain, he’s approached by Berger, a Norwegian agent of Free France, i.e., France’s resistance government-in-exile that was formed after the dissolution of the Third Republic. The emblem that Berger flashes to Laszlo is the same as the one we saw retrieved from a man shot dead by the police, earlier, in front of a propaganda poster featuring Philippe Petain’s craven visage.* These are Laszlo’s people.

* The poster’s slogan: “JE TIENS MES PROMESSES MEME CELLES DES AUTRES.” Petain accuses those in the Resistance of breaking the promises that Vichy made to the Germans when France surrendered.

The dominant discourse ingeniously deploys rhetoric to sway minds, to hypnotize the denizens of a semiosphere into believing there are no alternatives. Not merely words and images, but tonality — a tone of voice, a shrug of the shoulders, a lifted eyebrow, a little smirk or laugh — are what “sell” the discourse. Those who attempt to resist the dominant discourse must remain resolute against its seductive wiles.

When Renault introduces Major Strasser to Laszlo and Ilsa, at the Café Americain, we get a glimpse of this sort of thing. Strasser bows and smiles pleasantly, says, “How do you do? This is a pleasure I have long looked forward to.” His body language, facial expression, words, and tone suggest: This is normal. This is the way things are now. Though it’s difficult to resist courtesy and civility — one feels like a boor — Ilsa and Laszlo remain stone-faced, and don’t ask him to sit down.

When Strasser doesn’t depart, Laszlo says, “I’m sure you’ll excuse me if I am not gracious, but you see, Major Strasser, I’m a Czechoslovakian.” “You were a Czechoslovakian,” Strasser corrects him, firmly but not unkindly. “Now you are a subject of the German Reich!” Strasser is not wrong: Shortly before World War II, Czechoslovakia ceased to exist, and much of former Czechoslovakia came under the control of Nazi Germany. Strasser is speaking now to Laszlo in the mode of a schoolteacher, one whose recalcitrant pupil must learn his lesson.

Laszlo does not succumb to this rhetoric. Standing up — which helps counteract the sense that he is a schoolboy being lectured to by a superior — he announces, “I’ve never accepted that privilege, and I’m now on French soil.” This is how a counter-discourse operates: It doesn’t accept. Laszlo refuses to accept consensus reality; he rejects the counsel of experts and authority figures. He is being the change he wants to see in the world. [This counter-discourse mode is by no means the monopoly of progressives: cf. Trump and the MAGA movement.]

The following day, in Renault’s office, Strasser tries a different approach. Having failed to catch this elusive “fly” with honey, he now uses vinegar.

STRASSER: Very well, Herr Laszlo, we will not mince words. You are an escaped prisoner of the Reich. So far you have been fortunate enough in eluding us. You have reached Casablanca. It is my duty to see that you stay in Casablanca.

LASZLO: Whether or not you succeed is, of course, problematical.

Laszlo remains defiant — his reputation for courage is well-deserved. Strasser next attempts to bargain with him: He assumes, that is, that Laszlo is more driven by instrumental reason than moral reason.

STRASSER: You know the leaders of the underground movement in Paris, in Prague, in Brussels, in Amsterdam, in Oslo, in Belgrade, in Athens.

LASZLO: Even in Berlin.

STRASSER: Yes, even in Berlin. If you will furnish me with their names and their exact whereabouts, you will have your visa in the morning.

RENAULT: And the honor of having served the Third Reich.

LASZLO: I was in a German concentration camp for a year. That’s honor enough for a lifetime.

STRASSER: You will give us the names?

LASZLO: If I didn’t give them to you in a concentration camp where more “persuasive methods” you had at your disposal, I certainly won’t give them to you now.

Laszlo continues to demonstrate fortitude and courage. But we haven’t yet seen him in action as a rabble-rouser. Now, finally, the splendid and inspiring orator emerges:

LASZLO: And what if you track down these men and kill them? What if you murdered all of us? From every corner of Europe, hundreds, thousands, would rise to take our places. Even Nazis can’t kill that fast.

STRASSER: Herr Laszlo, you have a reputation for eloquence which I can now understand.

Laszlo next tries his powers of persuasion on Rick, who has insisted on his neutrality.

LASZLO: Isn’t it strange that you always happened to be fighting on the side of the underdog?

RICK: Yes. I found that a very expensive hobby, too. But then I never was much of a businessman.

PS: This scene is the precursor of the moment in Star Wars when Obi-Wan Kenobi approaches Han Solo about smuggling Luke and himself off Tattooine. However, George Lucas’s version of this scene is all business.

Rick’s hardboiled carapace seems impossible to crack. But then the sound of Major Strasser and his German confederates singing “Die Wacht am Rhein” downstairs comes to their ears. Laszlo marches out of Rick’s office and approaches the orchestra: “Play the ‘Marseillaise’! Play it!” Members of the orchestra glance toward the steps, toward Rick, who nods to them. An inspiring scene follows.

“Vive La France! Vive la democracie!” People clap and cheer, as the song ends. The rabble (I’m attempting to use this term in a non-pejorative way) has been roused. Strasser tells Renault: “You see what I mean? If Laszlo’s presence in a cafe can inspire this unfortunate demonstration, what more will his presence in Casablanca bring on?” In fact, Laszlo’s presence in the cafe has helped hasten Rick’s unwilling conversion to Laszlo’s cause — a conversion that will result in Strasser’s death at Rick’s hands.

In their penultimate meeting, Laszlo makes one final effort to recruit Rick to the cause.

RICK: Don’t you sometimes wonder if it’s worth all this? I mean what you’re fighting for?

LASZLO: You might as well question why we breathe. If we stop breathing, we’ll die. If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die.

RICK: What of it? Then it’ll be out of its misery.

LASZLO: You know how you sound, Monsieur Blaine? Like a man who’s trying to convince himself of something he doesn’t believe in his heart. Each of us has a destiny, for good or for evil.

RICK: Yes, I get the point.

LASZLO: I wonder if you do. I wonder if you know that you’re trying to escape from yourself — and that you’ll never succeed.

Laszlo isn’t the only person in Casablanca who understands that Rick is trying to escape from himself — and from his destiny “for good” — and will never succeed. But he’s the only one who puts it directly to Rick in this fashion. And despite Rick’s outward cynicism, as we’ll soon discover, Laszlo has succeeded in saving Rick’s soul.

Laszlo’s last words in the movie, from its final scene, are to Rick: “Welcome back to the fight. This time I know our side will win.”

Not only has the escape artist escaped once more, but he’s succeeded in setting Rick free from his hardboiled carapace… and converting him (back) to the anti-fascist cause.

FISHER OF MEN

The FISHER OF MEN thematic complex is diametrically opposed, in our Casablanca G-Schema, to the CRIME BOSS complex.

As with the other three “hybrid” paradigms, there’s another side to LASZLO. We might call this version “Victor,” as Ilsa does, instead of “Laszlo.” Laszlo is a liberator, while Victor is a lover. Ferrari, the crime boss, is selfish and concerned only with getting the job done; Victor, the fisher of men, is selfless, devoted not only to recruiting new members to the anti-fascist cause but to his wife, Ilsa. (So devoted, in fact, that he is willing to forgive Ilsa her every trangression, and to sacrifice himself to ensure her safety.) Ferrari, the crime boss, strategizes to secure Rick’s cafe and casino; Victor strategizes to save Rick’s soul.

The paradigm RENAULT, like LASZLO, is an avatar of this semiosphere’s PLEASURE territory. It is Renault who first raises the possibility that Victor Laszlo’s devotion to Ilsa may trump other concerns.

RENAULT: No matter how clever he is, he still needs an exit visa, or I should say, two.

RICK: Why two?

RENAULT: He is traveling with a lady.

RICK: He’ll take one.

RENAULT: I think not. I have seen the lady. And if he did not leave her in Marseilles, or in Oran, he certainly won’t leave her in Casablanca.

RICK: Maybe he’s not quite as romantic as you are.

Rick is wrong. Where Ilsa is concerned, Victor is nothing if not a romantic. Victor is torn, conflicted — his dedication to the cause is trumped by his dedication to Ilsa.

I’ve mentioned before that Star Wars is modeled, in certain key respects, on Casablanca, and it’s worth noting, at this juncture, that the paradigm LASZLO is “echoed” by the paradigm OBI-WAN.

Not in the sense that Laszlo is a fighting magic-user, of course! In a structural sense, though, both characters are powerful freedom fighters whom the heroine paradigm (ILSA, LEIA) seeks to recruit and activate for the rebellion… but both find their dedication to the cause tempted by another “calling.” For Obi-Wan, it’s his religious faith that lures away from the rebellion. For Victor, Ilsa — despite her dedication to the cause — is the lure.

Structurally speaking, these are not “orthogonal,” but “hemigonal” (if you will) dilemmas.

Though Rick cynically believed that Victor Laszlo would leave his female companion behind to save his own skin, the opposite turns out to be the case. After Victor meets with Ferrari, he attempts to persuade Ilsa to go on to safety without him.

LASZLO: Signor Ferrari thinks it might just be possible to get an exit visa for you.

ILSA: You mean for me to go on alone?

FERRARI: And only alone.

LASZLO: I will stay here and keep on trying. I’m sure in a little while —

FERRARI: We might as well be frank, Monsieur. It will take a miracle to get you out of Casablanca. And the Germans have outlawed miracles.

By staying behind, to save Ilsa, Victor risks imprisonment, torture, execution. Laszlo would never put the cause at risk in this manner; but Victor would. He deploys instrumental reason, to persuade Ilsa that it’s sensible, efficient, pragmatic for her to go on alone. But she knows that Victor is a creature of moral, not instrumental reason.

ILSA: But if the situation were different, if I had to stay and there were only a visa for one, would you take it?

LASZLO: Yes, I would.

ILSA: Yes, I see. When I had trouble getting out of Lille, why didn’t you leave me there? When I was sick in Marseilles for two weeks and you were in danger every minute, why didn’t you leave me then?

LASZLO: I meant to, but something always held me up.

Recognizing that he can’t bamboozle her, Victor says: “I love you very much, Ilsa.” Meaning: I love you so much that I’m willing to die for you. Rather than say that she loves him, too, Ilsa replies: “Your secret will be safe with me.” A sweet moment, and a telling one — Ilsa cares for Victor, but is she in love with him? Perhaps not.

Later, when Victor Laszlo attempts to purchase the letters of transit from Rick, he learns that Ilsa and Rick were lovers — two years earlier, when he’d been in a concentration camp and reported dead.

LASZLO: There must be some reason why you won’t let me have them.

RICK: There is. I suggest that you ask your wife.

LASZLO: I beg your pardon?

RICK: I said, ask your wife.

This exchange is, among other things, a kind of Matthew 4:1–11 moment. The saintly Victor is being tempted here, by the satanic Rick. From his own experience, Rick believes that a man who is deeply hurt by an unfaithful woman will recoil from her, become cynical and hardboiled. Once again, he has underestimated Victor.

Later that evening, Victor and Ilsa have a heart-to-heart talk.

“Victor, why don’t you tell me about Rick?” she asks. “What did you find out?” It’s a double question: What did Victor find out about the letters of transit, and… did Rick tell Victor about their love affair?

Victor tells Ilsa what Rick said. She knows that Victor understands what this means, but she’s too conflicted and ashamed to speak. Sitting beside her, Victor gently encourages her to come clean.

LASZLO: When I was in the concentration camp, were you lonely in Paris?

ILSA: Yes, Victor, I was.

LASZLO: I know how it is to be lonely. Is there anything you wish to tell me?

ILSA: No, Victor, there isn’t.

LASZLO: I love you very much, my dear.

ILSA: Yes, yes I know. Victor, whatever I do, will you believe that I, that —

LASZLO: You don’t even have to say it. I’ll believe.

Ilsa has confessed without confessing — and once again, she hasn’t responded in kind to an “I love you” from Victor. (One thinks of the iconic exchange from the Star Wars sequel The Empire Strikes Back, in which Leia says “I love you” to Han. Han replies: “I know.”) None of which changes the way that Victor feels about Ilsa; he is stronger, kinder, more compassionate. and less self-involved than Rick.

Has Rick come to comprehend this side of Victor Laszlo? He has: In the scene where Ilsa confesses that she still loves Rick, and is willing to leave Victor for him, she says: “Oh, you’ll help him now, Richard, won’t you? You’ll see that he gets out? Then he’ll have his work, all that he’s been living for.” “All except one,” Rick says. “He won’t have you.” It’s an equivocal moment: Is he gloating? That’s what he’d like Ilsa to believe, perhaps. But in fact… thanks to Victor’s example, he’s beginning to understand that he mustn’t steal Ilsa.

In their final one-on-one scene, the paradigms LASZLO and RICK shuttle back and forth between each of the paradigm’s two aspects.

- The hardboiled “Rick” wants to make a favorable deal.

- The rabble-rousing “Laszlo” wants to escape, and keep fighting fascism.

- The idealistic “Richard” wants to do what’s politically and morally right.

- The hopelessly smitten “Victor” is willing to sacrifice himself for Ilsa.

RICK: You seem to know all about my destiny.

LASZLO: I know a good deal more about you than you suspect. I know, for instance, that you are in love with a woman. It is perhaps strange that we both should be in love with the same woman. The first evening I came here in this cafe, I knew there was something between you and Ilsa. Since no one is to blame, I — I demand no explanation. I ask only one thing. You won’t give me the letters of transit — all right, but I want my wife to be safe. I ask you, as a favor, to use the letters to take her away from Casablanca.”

RICK: You love her that much?

LASZLO: Apparently you think of me only as the leader of a cause. Well, I am also a human being. Yes, I love her that much.

“Victor,” in this scene, has trumped “Laszlo.” But will “Richard” trump “Rick”? We’re left in suspense about that… until the end.

As described above, we see Victor Laszlo code-switch, in this scene, between “Victor” and “Laszlo.” The counter-discourse paradigm of any semiosphere tends to be chameleon-like.

In Star Wars, for example, we’re introduced to the ex-freedom fighter Obi-Wan Kenobi as “old Ben,” a gentle and eccentric seeker of wisdom. When he first meets Luke, Ben is all smiles… until Luke says that he’s seeking Obi-Wan Kenobi. Ben’s face morphs from kindly to grim. “Now that’s a name,” he says as much to himself as to Luke, “I’ve not heard in a long time — a long time.”

Kenobi is transforming, before our eyes, from “Ben” to “Obi-Wan.”

Rick lies to Victor, in their final scene, saying of Ilsa: “She tried everything to get [the letters of transit], and nothing worked. She did her best to convince me that she was still in love with me, but that was all over long ago. For your sake, she pretended it wasn’t, and I let her pretend.” (As in Ferrari’s final scene, where we see FERRARI’s two aspects both come into play, here we see RICK’s two aspects… but we’ll discuss that when we get to the RICK installment.) Rick understands that Laszlo’s two aspects are codependent; he can’t fight fascism without Ilsa at his side.

Hard-to-budge figures like Rick Blaine can’t be moved by rhetoric alone. I’ve described the LASZLO paradigm as a “fisher of men” (a line from Matthew 4:19), and it’s important to note that a charismatic leader like Victor Laszlo isn’t merely a rabble-rouser. He appeals not only to one’s sense of right and wrong, but directly to one’s heart.

As per Kristeva’s theory of abjection, the PEACE and PLEASURE-championing paradigm LASZLO rejects and disturbs “social reason” — i.e., the communal consensus that underpins the WAR and BUSINESS-oriented social order of the Casablanca semiosphere. “Since the abject is situated outside the symbolic order,” Kristeva writes, “being forced to face it is an inherently traumatic experience.” Lazlo is a disruptive change agent.

Whereas Ferrari deftly avoids entanglement with Laszlo, thus preserving his status, by the end of the movie Rick will emerge transformed from his traumatic conflict with Laszlo.

Next CASABLANCA CODES series installment: STRASSER.

All series installments: FERRARI | LASZLO | STRASSER | ILSA | UGARTE | YVONNE | RICK | RENAULT.